The Vagus Nerve, Inflammation, and the Neck: How are They Connected?

In my traditional medical education, there were nerves and there was a phenomenon called inflammation, and the two were never interrelated. Inflammation happened because of trauma or a chemical pathway that went haywire in diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, and nerves were activated to retrieve information like the sensation or to tell a body part what to do. However, the research showing that nerves and inflammation are very much related is now getting mature, and one nerve in particular, the vagus, may play a big role. In addition, that may show us how neck instability could cause chronic systemic inflammation. So let’s dive in.

Inflammation 101: Good vs. Bad

The inflammation in your body comes in two general types, one good and one bad. Acute inflammation that resolves rapidly and is appropriate for its context is what happens when a young and healthy person sprains an ankle. The area swells, and in a few days, the swelling resolves. That kind of inflammation is good, with recent research showing that using NSAID drugs like Motrin, Ibuprofen, Advil, or Alleve causes chronic pain by blocking this healthy form of inflammation (1). On the other hand, treatments like prolotherapy, PRP, and Bone Marrow Concentrate can increase this healthy form of inflammation in the short term to cause tissues to heal.

The second form of inflammation is chronic, which means that it doesn’t promptly resolve and sticks around. This type of inflammation is bad and results in all sorts of common diseases of the industrialized world, like heart attacks, stroke, and arthritis (2).

Inflammation and the Nervous System

So how does your body know how to begin the good inflammation? What turns the good acute inflammation into the bad chronic type? How does that involve nerves?

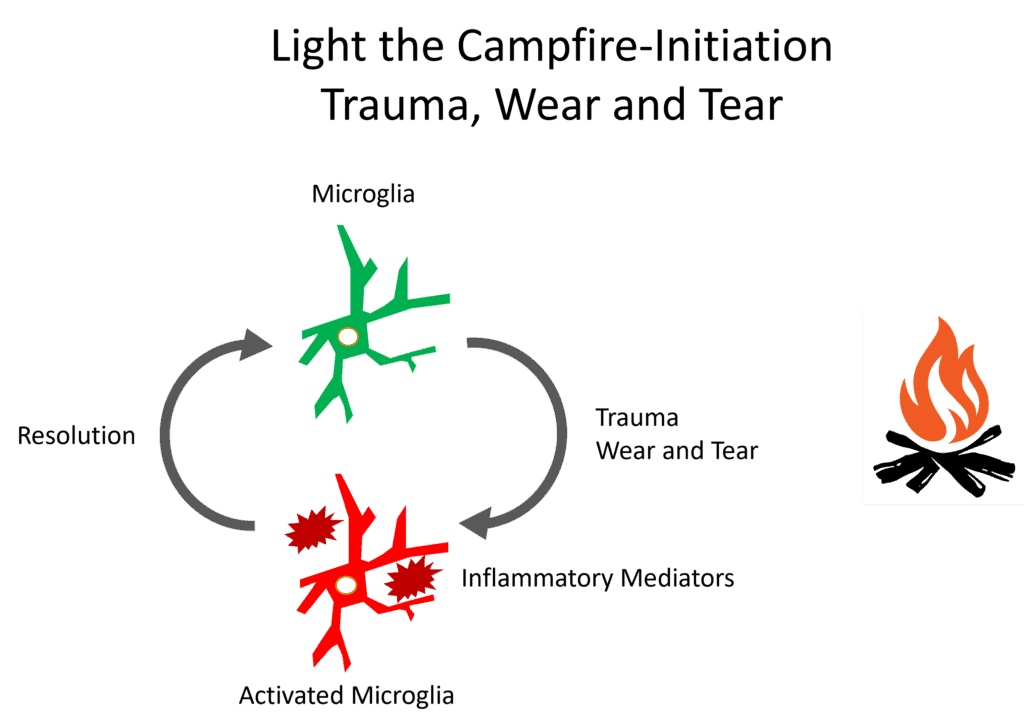

Credit: Author

Trauma or wear and tear can produce inflammatory mediators which activate microglia, which is a type of specific cell present in your nervous system (3). That “initiates” your nervous system to activate the inflammation response. That will set off a process that includes three predictable phases, which include acute inflammation (lasting 3-7 days), the proliferation of new cells to replace dead ones (can last 3-21 days), and the remodeling of those new cells into healthy tissue (lasts 21 days to 2 years).

Note that we can use a campfire analogy. In the case of good inflammation, the microglia get activated and can be easily deactivated when the inflammation resolves. That’s much like a campfire begun in a wet environment in the woods. You can start it, and when the wood is exhausted, it burns itself out without setting the forest on fire.

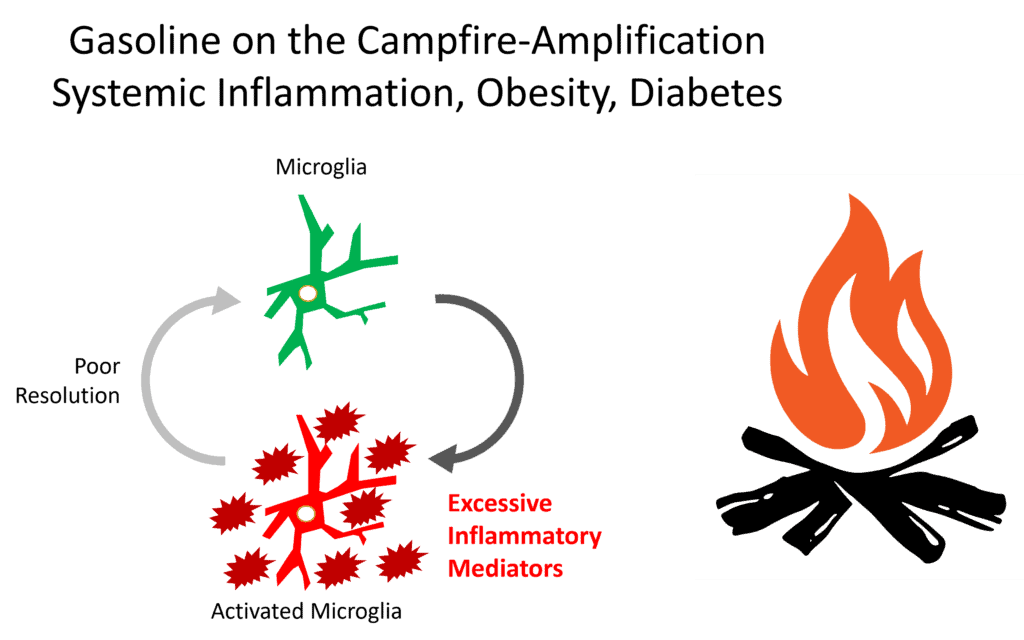

Chronic inflammation is very different. We get the same microglial activation, but because of a problem with systemic inflammation, obesity, and/or diabetes, there are excessive inflammatory mediators around. This amplifies the inflammatory signaling, and there is too much inflammation without any resolution. Meaning the “on” switch continues to get activated while the “off” switch never does.

To return to our campfire analogy, these inflammatory mediators act like gasoline on our campfire and dry out the surrounding forest. So our inflammatory fire burns out of control and does “burn down the forest”.

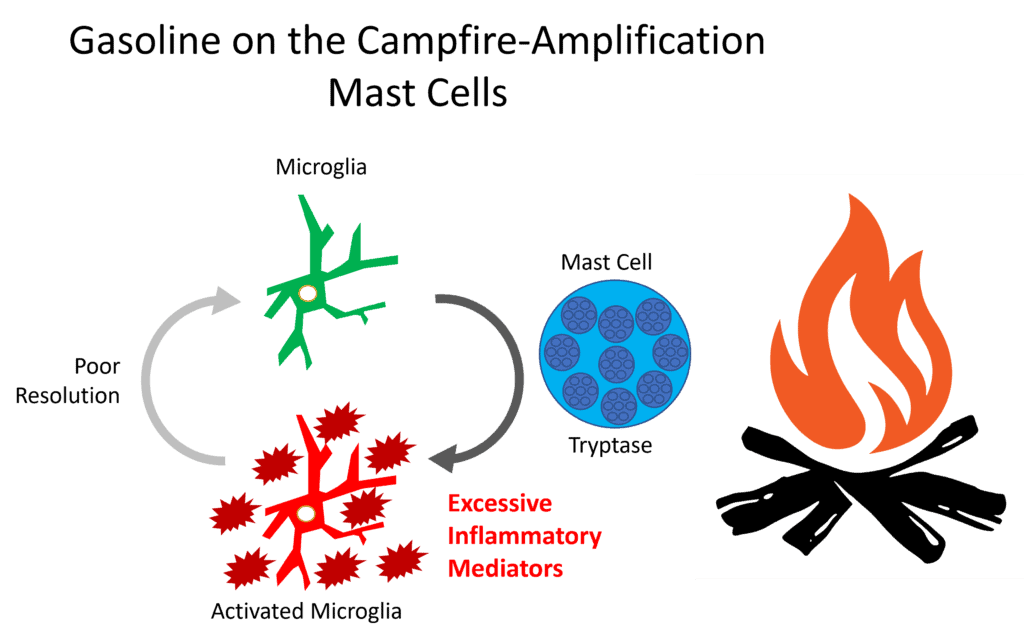

Credit: Author

In addition, another pathway that can cause chronic inflammation is through mast cells. These cells are normally associated with the normal response to bacteria and other invaders (7). However, in some patients, the mast cell system can spin out of control, and when that happens, it’s called MCAS (MAST Cell Activation Syndrome) (8). This also adds gasoline to the inflammation campfire, as shown above.

So how is the signal to turn off this inflammation processed by the body? Let’s get into the vagus nerve first and how that works after that deep dive.

The Vagus Nerve

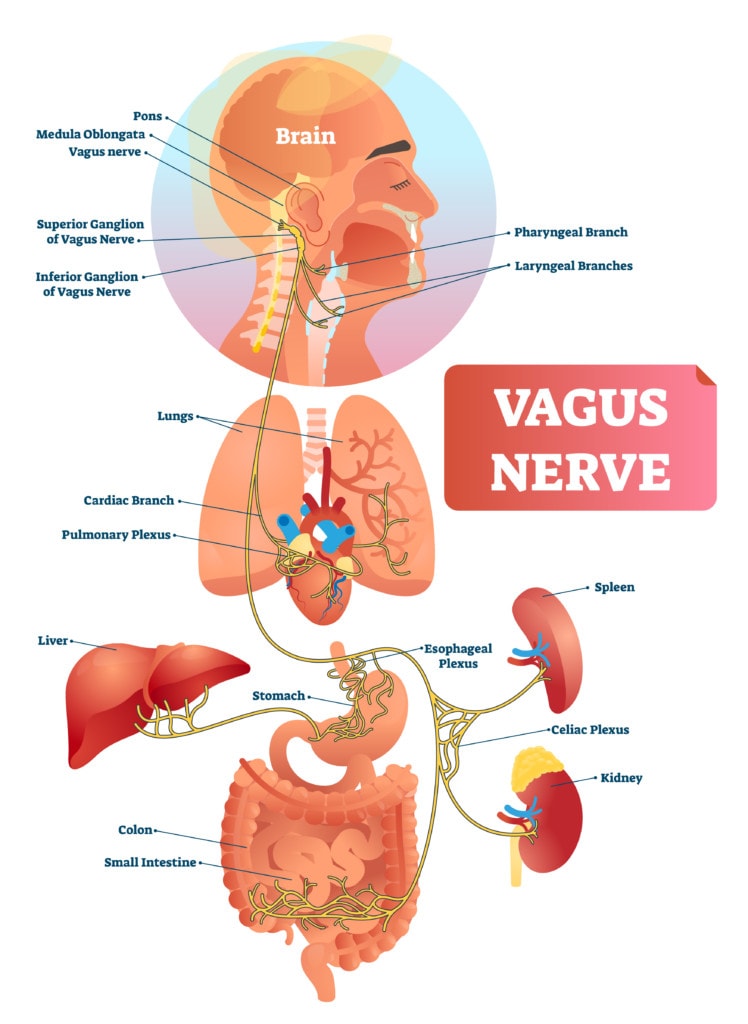

Credit: Shutterstock

The vagus nerve gets its name from the Latin word “wanderer.” That’s because it’s the longest-named nerve in the body that begins in the skull as the 10th cranial nerve and “wanders” past the upper neck, where it has several ganglia, and then all the way into the chest, where it sends signals to the heart and then finally into the abdominal cavity where it signals the gut and major organs (4).

The vagus nerve is a major player in the yin and yang of the parasympathetic and sympathetic systems. The parasympathetic system, when activated through the vagus nerve, allows your body to relax, which causes your heart rate to lower, the gut to digest, and signals that it’s time to repair. The opposite is the sympathetic system which is when the vagus nerve is not stimulated, which is your “fight or flight” mode. This causes rapid heart rate and your gut to shut down.

The Vagus Nerve and Inflammation

Credit: Author

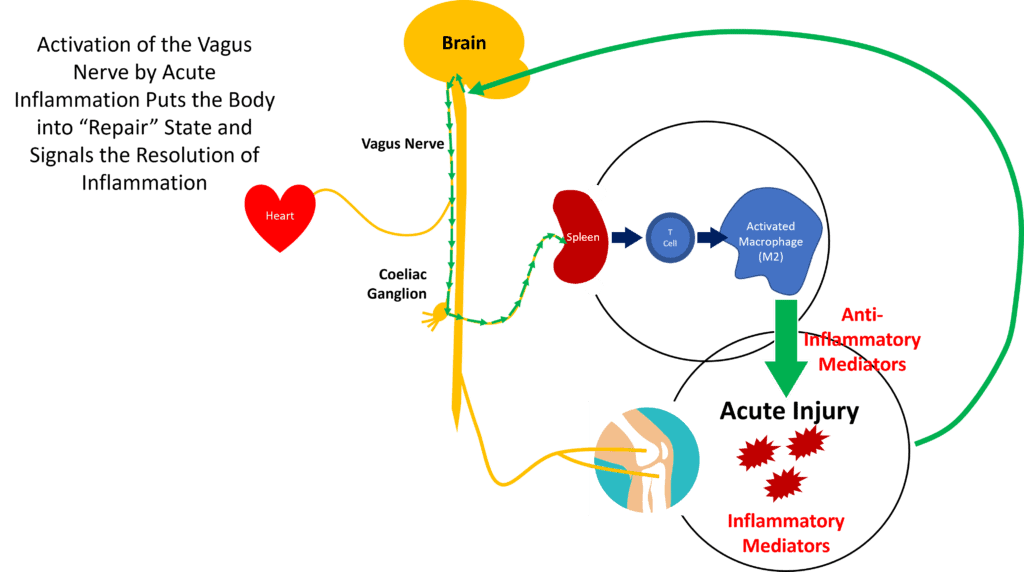

Now let’s get into that inflammation “off” switch discussed above.

The vagus nerve is involved in both reducing acute and stoking chronic inflammation (5). This is called the “Neural Reflex Mechanism” (NFR). Basically, the sensors on the ground in the body pick up inflammatory signals caused by acute inflammation, which make their way to the brain. The brain signals through the vagus nerve that it’s time to get into repair mode. That pathway is activated through the coeliac plexus to the spleen, which manufactures chemicals to resolve the inflammation (17).

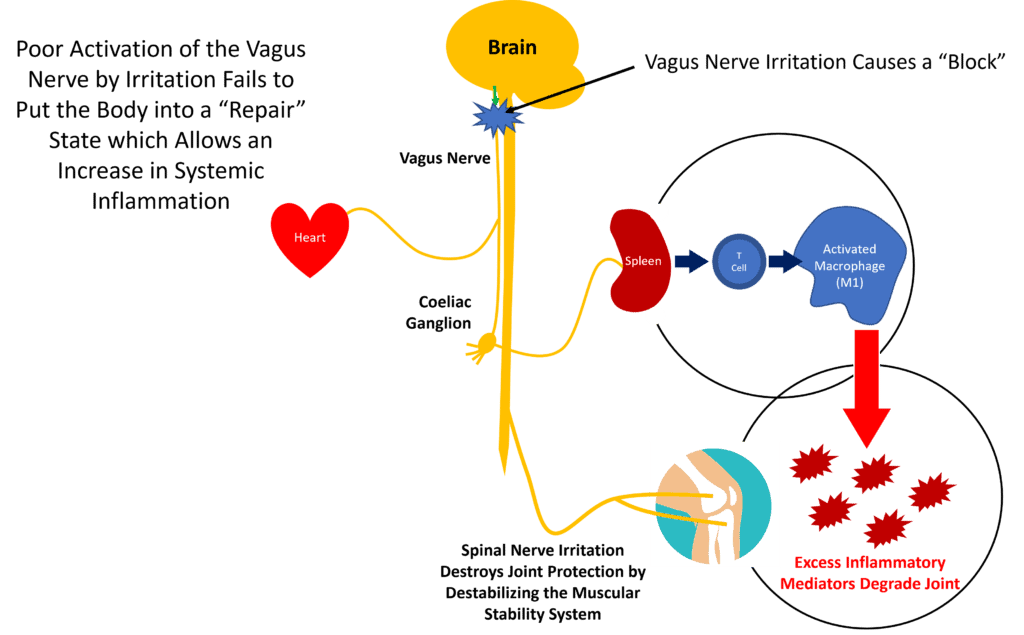

Credit: Author

So what happens if the brain detects lots of inflammation, as shown above when we discussed microglia, but cannot activate the cells in the spleen to produce anti-inflammatory mediators? Then inflammation can spin out of control and begin to degrade joints, as shown above. This is why device companies have discussed using vagal nerve stimulators as a way to activate the vagus nerve to control this type of systemic inflammation (6, 16).

How Can the Vagus Nerve Get Irritated, and What Does this Have to Do with Neck Problems?

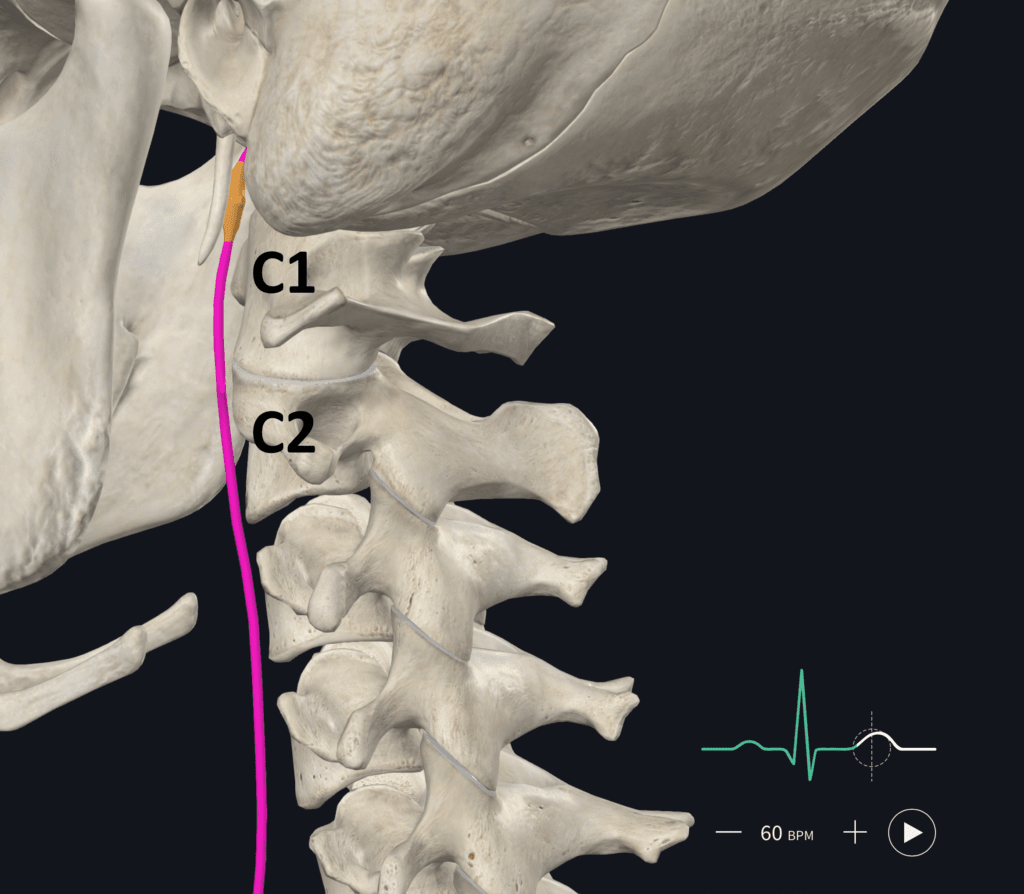

Credit: Elsevier Complete Anatomy with Annotations by the Author

The vagus nerve exits the skull and travels in front of the upper cervical spine, as shown above. Hence, if there is craniocervical (C0-C2) or C2-C3 instability, it can be irritated, and in my clinical experience, this can produce all of the symptoms of a vagus nerve block.

Also, in my clinical experience and the published research, the best way to determine if the type of instability that can irritate the vagus nerve is present is by using Digital Motion X-ray (DMX) (9). Next, if the instability is in the high upper neck (CCI or craniocervical instability), generally, the alar/transverse ligaments need to be directly targeted with orthobiologics with a procedure like PICL. If the problem is C2-C3 instability, traditional posterior ligament injection can help.

Is There Face Validity that Treating the Neck Can Reactivate the Vagus Nerve?

“Face Validity” means that, on its face, the idea sounds credible. As shown above, we know that the vagus nerve runs right in front of the upper cervical vertebrae. I have also treated countless CCI patients who have clear vagal nerve block symptoms like rapid heart rate, GI problems, and chronic fight or flight and who have had these symptoms resolve when instability remits using direct injection of the upper neck ligaments.

What does the research say? We know that in animal models, there are connections between the C1 neurons and the vagus nerve (11, 12). Physical therapists have postulated that neck tightness and vagal nerve irritation may be connected as they have also observed the resolution of gut symptoms by treating the neck (13). In addition, researchers testing cervical vagal nerve stimulation have been able to reverse heart failure by improving autonomic regulation (14). The recently discovered ALCAO plexus that lives in front of the C1-C2 joint receives significant innervation by the vagus nerve (15). Finally, osteopathic manipulation of the upper cervical spine enhanced heart rate variability versus sham manipulation (18).

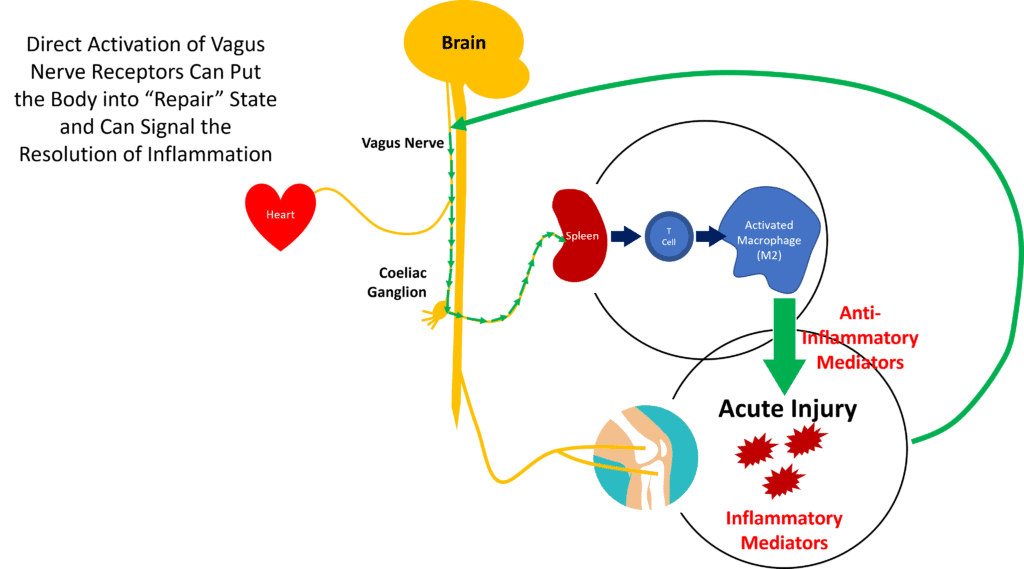

New Research on How the Vagus Nerve Is Involved Directly in Detecting Inflammation

Credit: Author

How the above feedback loop happens, with inflammatory chemicals being detected by the nervous system and the signals to quash inflammation traveling through the vagus nerve, is still being researched. However, researchers in New York recently created an “inflammatory storm” in an animal model and determined that receptors directly in the vagus nerve detected that inflammation, which activated the feedback loop to shut down the excessive inflammation (10). They could also quash the inflammation by stimulating cells in the vagus nerve with light, lending further credence to the idea that vagus nerve stimulation may be able to treat this problem.

The upshot? The vagus nerve plays a unique role in controlling inflammation. When irritated in the neck, the “vagal block” can cause systemic inflammation to run out of control. In addition, if you add things like obesity, diabetes, MCAS, or systemic inflammation into the mix, that’s like throwing gasoline on a campfire. Hence, if the vagus nerve block site can be identified as being caused by neck instability like CCI, then reducing that instability through specific image-guided orthobiologic injections makes sense.

______________________________________________

References:

(1) RNSA. NSAIDs May Worsen Arthritis Inflammation. https://press.rsna.org/timssnet/media/pressreleases/14_pr_target.cfm?id=2379#. Accessed 1/23/23.

(2) Pahwa R, Goyal A, Jialal I. Chronic Inflammation. 2022 Aug 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 29630225.

(3) Skaper SD, Facci L, Zusso M, Giusti P. An Inflammation-Centric View of Neurological Disease: Beyond the Neuron. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018 Mar 21;12:72. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00072. Erratum in: Front Cell Neurosci. 2020 Feb 03;13:578. PMID: 29618972; PMCID: PMC5871676.

(4) Johnson RL, Wilson CG. A review of vagus nerve stimulation as a therapeutic intervention. J Inflamm Res. 2018 May 16;11:203-213. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S163248. PMID: 29844694; PMCID: PMC5961632.

(5) Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ. The vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex–linking immunity and metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(12):743-754. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2012.189

(6) Bonaz B, Sinniger V, Pellissier S. Anti-inflammatory properties of the vagus nerve: potential therapeutic implications of vagus nerve stimulation. J Physiol. 2016;594(20):5781-5790. doi:10.1113/JP271539

(7) Krystel-Whittemore M, Dileepan KN, Wood JG. Mast Cell: A Multi-Functional Master Cell. Front Immunol. 2016 Jan 6;6:620. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00620. PMID: 26779180; PMCID: PMC4701915.

(8) Frieri M, Patel R, Celestin J. Mast cell activation syndrome: a review. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2013 Feb;13(1):27-32. doi: 10.1007/s11882-012-0322-z. PMID: 23179866.

(9) Freeman MD, Katz EA, Rosa SL, Gatterman BG, Strömmer EMF, Leith WM. Diagnostic Accuracy of Videofluoroscopy for Symptomatic Cervical Spine Injury Following Whiplash Trauma. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Mar 5;17(5):1693. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051693. PMID: 32150926; PMCID: PMC7084423.

(10) Silverman, H.A., Tynan, A., Hepler, T.D. et al. Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin-1-expressing vagus nerve fibers mediate IL-1β induced hypothermia and reflex anti-inflammatory responses. Mol Med 29, 4 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10020-022-00590-6

(11) Qing-Gong F, Chandler MJ, McNeill DL, Foreman RD. Vagal afferent fibers excite upper cervical neurons and inhibit activity of lumbar spinal cord neurons in the rat. Pain. 1992 Oct;51(1):91-100. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90013-2. PMID: 1454410.

(12) Qin C, Chandler MJ, Jou CJ, Foreman RD. Responses and afferent pathways of C1-C2 spinal neurons to cervical and thoracic esophageal stimulation in rats. J Neurophysiol. 2004 May;91(5):2227-35. doi: 10.1152/jn.00971.2003. Epub 2003 Dec 24. PMID: 14695350.

(13) Ozel Asliyuce Y, Berberoglu U, Ulger O. Is cervical region tightness related to vagal function and stomach symptoms? Med Hypotheses. 2020 Sep;142:109819. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109819. Epub 2020 May 6. PMID: 32408072.

(14) Premchand RK, Sharma K, Mittal S, Monteiro R, Dixit S, Libbus I, DiCarlo LA, Ardell JL, Rector TS, Amurthur B, KenKnight BH, Anand IS. Autonomic regulation therapy via left or right cervical vagus nerve stimulation in patients with chronic heart failure: results of the ANTHEM-HF trial. J Card Fail. 2014 Nov;20(11):808-16. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.08.009. Epub 2014 Sep 1. PMID: 25187002.

(15) Yang S, Iwanaga J, Olewnik Ł, Konschake M, Loukas M, Dumont AS, Ottone NE, Sañudo J, Tubbs RS. The Anterolateral Cervical Atlanto-Occipital Plexus: A Novel Finding with Application to Skull Base and Spine Surgery and Pain Disorders of the Head and Neck. World Neurosurg. 2022 Mar;159:e84-e90. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.12.008. Epub 2021 Dec 8. PMID: 34896353.

(16) Chen H, Feng Z, Min L, et al. Vagus Nerve Stimulation Reduces Neuroinflammation Through Microglia Polarization Regulation to Improve Functional Recovery After Spinal Cord Injury. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:813472. Published 2022 Apr 7. doi:10.3389/fnins.2022.813472

(17) Zhang, L., Liu, Y., Wang, S., Long, L., Zang, Q., Ma, J., Yu, L., & Jia, G. (2021). Vagus nerve stimulation mediates microglia M1/2 polarization via inhibition of TLR4 pathway after ischemic stroke. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 577, 71-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.09.004

(18) Giles PD, Hensel KL, Pacchia CF, Smith ML. Suboccipital decompression enhances heart rate variability indices of cardiac control in healthy subjects. J Altern Complement Med. 2013 Feb;19(2):92-6. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0031. Epub 2012 Sep 20. PMID: 22994907; PMCID: PMC3576914.

If you have questions or comments about this blog post, please email us at [email protected]

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.