Surgery for Tethered Cord in Adults?

One of the trends I have seen these past few years is a number of people getting diagnosed with a tethered cord and getting surgery for this issue. So what is this and why would surgery be needed? Are these patients getting needed procedures or exposing themselves to serious risks they don’t need to take? Let’s dig in.

What Is a Tethered Spinal Cord?

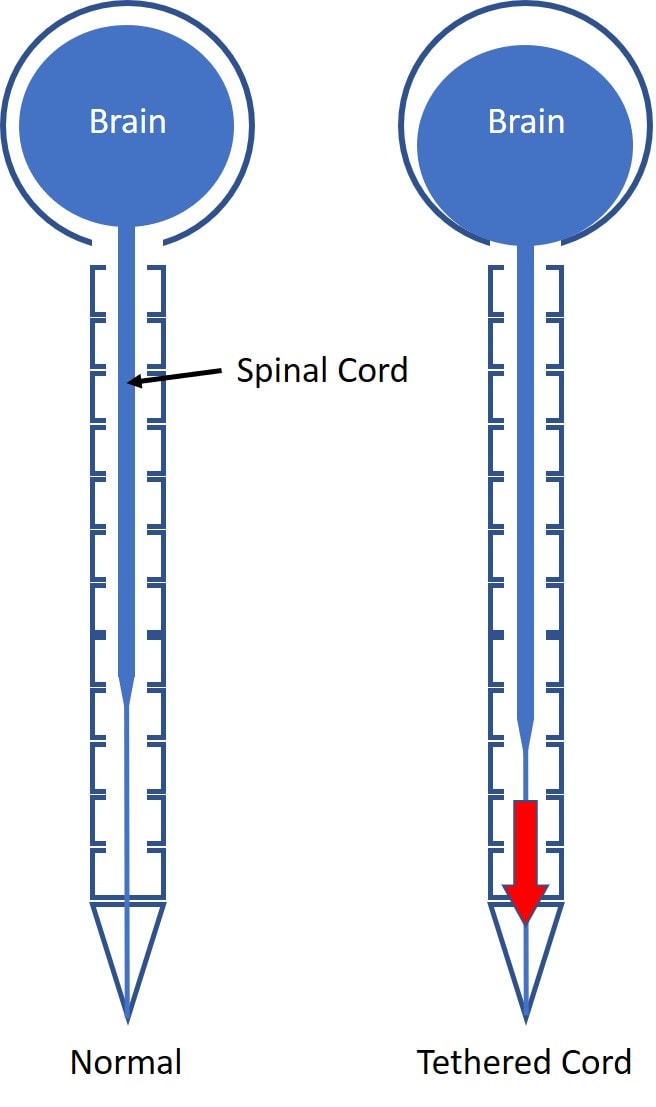

At its most basic, your spinal cord projects down from your brain and contains the major wiring that tells your muscles to move and allows you to feel things. It’s connected to the brain and travels through the spinal bones (vertebrae) and usually ends at the lowest part of the upper back (T11-L1). There are nerves below that called the cauda equina (horse’s tail). There’s also a piece of connective tissue that anchors it from below called the filum terminale (filum).

When something from below causes the filum to get stuck, like a tumor or scarring from prior low back surgery, the filum can yank on the cord and pull it down as shown below. When that happens, it’s called a “tethered cord” (1).

Most of the pressure is on the lower part of the spinal cord with the connective tissue of the cord diffusing the pressure as you go up. That’s why most of the symptoms are in the low back and legs (lower spinal cord and nerves). However, another aspect of that diagram to the right is that some believe that a tethered cord can also pull on the brain and cause it to hang low in the skull base, intersecting with a disease called “Chiari Malformation”. More on that below.

The most frequent tethered cord patient is usually a kid with Spina Bifida. It can be congenital (the person is born with it) or acquired later in life. If it’s the later, there is usually something pulling on the filum terminale or it’s stuck on a physical obstruction or scarred down. That obstruction can be a fatty tumor, a spinal cord tumor, or a bone spur. In addition, local scarring of the nerve roots after back surgery (i.e. failed back syndrome) is also a known cause. In rare instances, this problem can also be seen in scoliosis.

Symptoms

Symptoms include back pain that radiates to the legs, hips, and genital or rectal areas. There can also be bowel and/or bladder issues. The legs can feel numb or tingly and in some patients get weak or begin to lose muscle.

Diagnosis

This is where you need to break an adult with a tethered cord into two camps: traditional and non-traditional. For traditional tethered cord due to masses in the spinal canal or prior back surgery, the diagnostic criteria is that the end of the spinal cord is low, below L2 (normally at T12 or L1) with a thickened filum. However, for non-traditional where there is no mass or prior back surgery, the diagnosis is can also be made on clinical symptoms, abnormal urodynamics, and a lack of other things helping the condition.

Urodynamics

One of the items that advocates point to as an indication for the surgery is urodynamics. This is testing of the bladder performed by a urologist that can identify a “neurogenic bladder”. The concern I have is that we have seen many patients through the years with sacral nerve irritation with a neurogenic bladder on urodynamic studies. These are commonly patients with a central L5-S1 disc bulge that irritates the descending sacral nerves or chronic SI joint syndrome that irritates the sacral nerves. Their symptoms and urodynamic studies normalize after a simple caudal epidural to reduce this nerve inflammation. So this usual cause of a neurogenic bladder would need to be ruled out in surgical detethering candidates before a procedure was performed.

Surgery for Tethered Cord

The most common surgery for tethered cord involves cutting the anchoring tissue on the bottom called the filum terminale. This is called “detethering”. Complications include infection, bleeding, and damage to the spinal cord, which may result in paralysis or loss of bowel or bladder function.

Tethered Cord in Adults

So if a tethered cord is a diagnosis normally found in kids with spina bifida and adults who have rare spinal tumors or prior back surgery gone bad, how is it that some patients who fit none of those descriptions are now getting surgery to treat this issue?

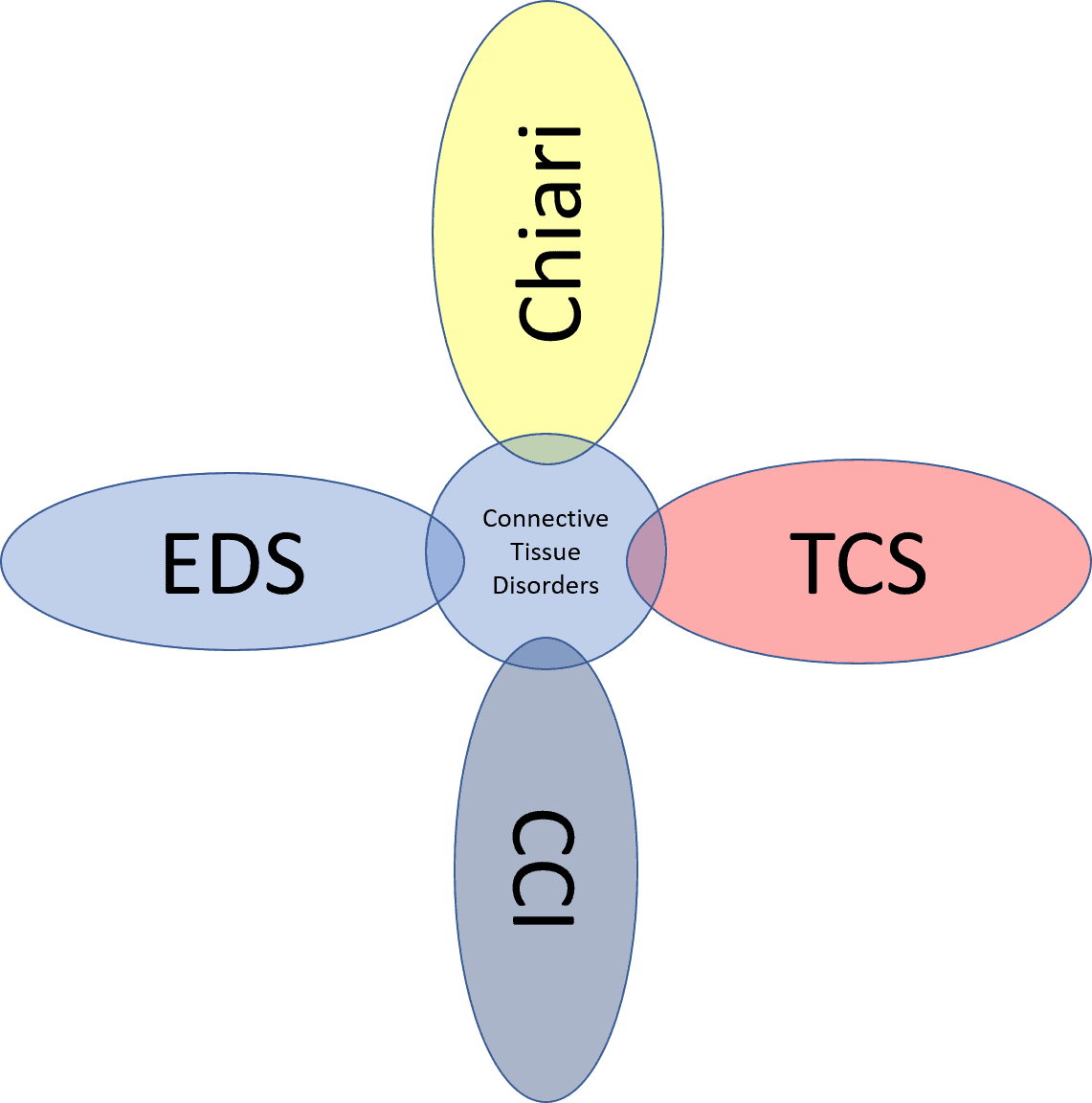

The diagram above is how various problems may intersect with tethered cord.

The connection between tethered cord surgeries and adult patients starts with Chiari malformation (3). This is a problem where the brain is hanging low in the skull and the bottom part (the cerebellum) can get pushed into the spinal canal. While this is a rare and serious medical condition. more recently we’ve seen a huge number of surgeries being performed for Chiari problems that were previously never operated (Chiari 1 and 0). In these cases, the brain is only minimally pushed downward or barely so. I’ve seen many of these patients post-surgery in the clinic who are no better and in many ways worse, but now they have a huge hole carved in the back of their skull and their upper neck biomechanics are permanently altered for the worse.

The new concept that’s pushing patients toward detethering surgeries is an overlap between Chiari malformation and a tethered cord. This is still pretty controversial, as the biomechanics of the spinal cord don’t necessarily support that this is possible. Meaning that any downward force from a tight filum would be absorbed by the lower spinal cord.

Despite this, there are patients (and a handful of neurosurgeons) who believe in the diagram on the right as seen above. That is that a tethered cord is pulling the brain down, thus leading to Chiari malformation thus these patients require detethering. That interfaces with EDS (Ehlers Danlos Syndrome) patients, who have super stretchy ligaments, because it’s believed that the connective tissue that normally anchors the brain and holds it up is too loose, thus allowing it to hang low in the skull (4). Hence, the rationale is that they too may need detethering to reduce the downward pull on the brain.

So how do we get from CCI (craniocervical instability) to detethering? These patients have damage to the ligaments that hold the head onto the spine. However, some CCI patients have EDS, which is likely why a handful of patients with CCI are considering getting their filum cut.

Research?

I searched the US National Library of medicine for any research on the following topics:

- Adult Tethered Cord Syndrome – Not much on PubMed using that search, but more on Google Scholar-A case series that again doesn’t apply to this discussion as the detethering was performed for traditional causes of tethering like tumors. Or this overview paper that again focuses on kids or adults with spinal masses or prior back surgery. This is a theoretical paper on this actual topic (adults with symptoms without known masses causing tethering) but provides no higher level clinical data. This paper describes 24 patients treated over 11 years who didn’t have masses and had a primary presentation of backpain. In reviewing many of these listed papers, most again focus on patients with traditional causes of a tethered cord and not on adults with no known risk factors who suddenly develop symptoms.

- Ehlers Danlos Syndrome and detethering – NONE

- Chiari Malformation and detethering – Some, no high-level research, most in kids with spina bifida or other common causes of tethered cord like tumors.

- Craniocervical instability detethering – 2 hits-one case report on a rare congenital defect and a surgery planning study for C1 screw placement. Meaning zip on an adult with CCI getting a detethering procedure.

What Could Go Wrong?

This is the mantra that every patient considering an invasive surgery like cutting the connection of the spinal cord needs to consider. Almost all of the research on detethering and possible complications is done in kids with spina bifida. Unfortunately, most of these kids don’t walk and have severe functional and developmental delays. Meaning that detecting complications in this group would be very tough. In an adult who walks and talks and otherwise isn’t wheelchair-bound, the significance of complications that could include never walking again is a much bigger deal. However, we have no real reports of the complications of detethering in this new group of patients getting the surgery.

Should You Get Chiari or Detethering Surgery?

These are NOT first-line treatments. Carving a hole in the back of your skull to treat a mild Chiari malformation is something that is a last-ditch effort to treat someone who is otherwise functionally disabled and who has tried everything else less invasive. The same holds true for cutting the connection for the spinal cord.

One of the big problems that I see is that the filum terminale is there for a reason. It anchors the spinal cord and nerve roots. Cutting it will permanently impact the biomechanics of how your spinal cord and spinal nerve roots move. Once that’s done, there is no going back and reconnecting it.

The upshot? Surgery for a tethered cord is a last-ditch option in a patient who is disabled and has explored all other non-surgical options. It is not a primary treatment for someone who has a mild Chiari malformation, EDS, and/or CCI. Please be careful out there as most of these surgeries are biomechanical one-way streets. If they work, everyone’s happy, but when they don’t work, the patient is left with permanent damage and a change to their biomechanics that can never be fixed.

_________________________________________

References:

(1) Düz B, Gocmen S, Secer HI, Basal S, Gönül E. Tethered cord syndrome in adulthood. J Spinal Cord Med. 2008;31(3):272-278. doi:10.1080/10790268.2008.11760722

(2) O’Connor KP, Smitherman AD, Milton CK, Palejwala AH, Lu VM, Johnston SE, Homburg H, Zhao D, Martin MD. Surgical Treatment of Tethered Cord Syndrome in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2020 May;137:e221-e241. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.01.131. Epub 2020 Jan 28. PMID: 32001403.

(3) Talamonti G, Marcati E, Mastino L, Meccariello G, Picano M, D’Aliberti G. Surgical management of Chiari malformation type II. Childs Nerv Syst. 2020 Aug;36(8):1621-1634. doi: 10.1007/s00381-020-04675-7. Epub 2020 May 30. PMID: 32474814.

(4) Mancarella C, Delfini R, Landi A. Chiari Malformations. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2019;125:89-95. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-62515-7_13. PMID: 30610307.

If you have questions or comments about this blog post, please email us at [email protected]

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.