What is Intracranial Hypertension? What Does It Have to Do with the Neck?

Since we see many patients with neck pain and headaches, the topic of intracranial hypertension seems to be more common these days. So what is intracranial hypertension and what does it have to do with headaches? Is it caused by internal jugular vein (IJV) compression? What is IJV compression? Can neck problems make it worse? Do you need surgery? Let’s dig into these topics.

What is Intracranial Hypertension?

In the context in which we will be reviewing it today, intracranial hypertension is the backup of blood or cerebral spinal fluid in the brain. Our focus will be on what can happen when the internal jugular vein is compressed as that could have some cross-over with neck problems.

What is the Internal Jugular Vein?

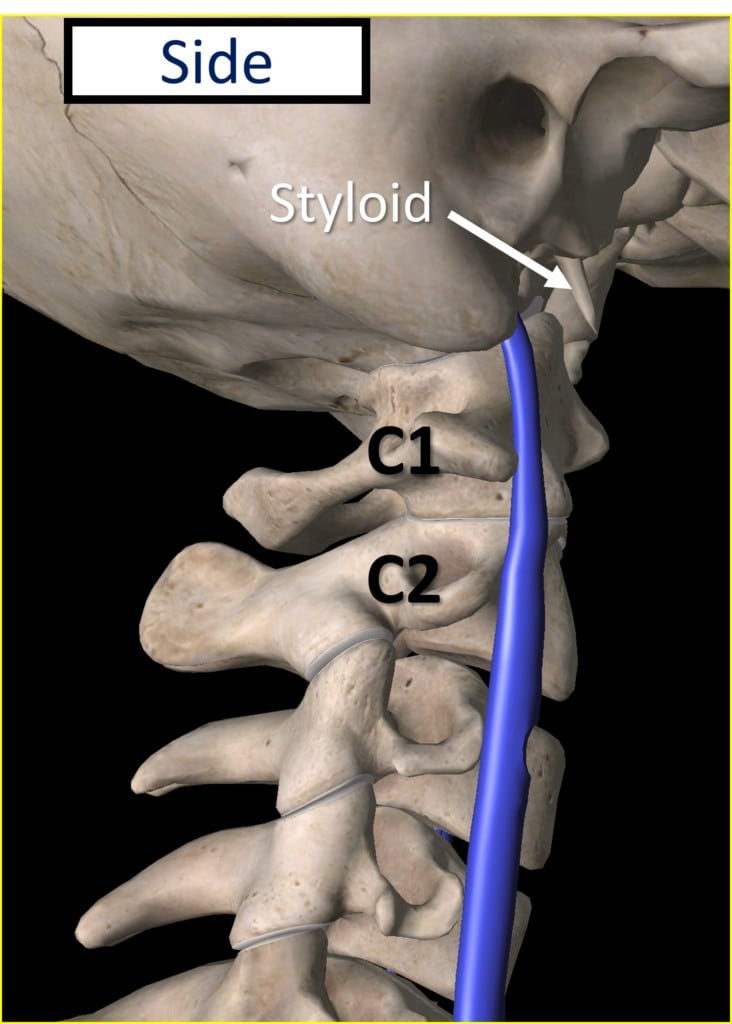

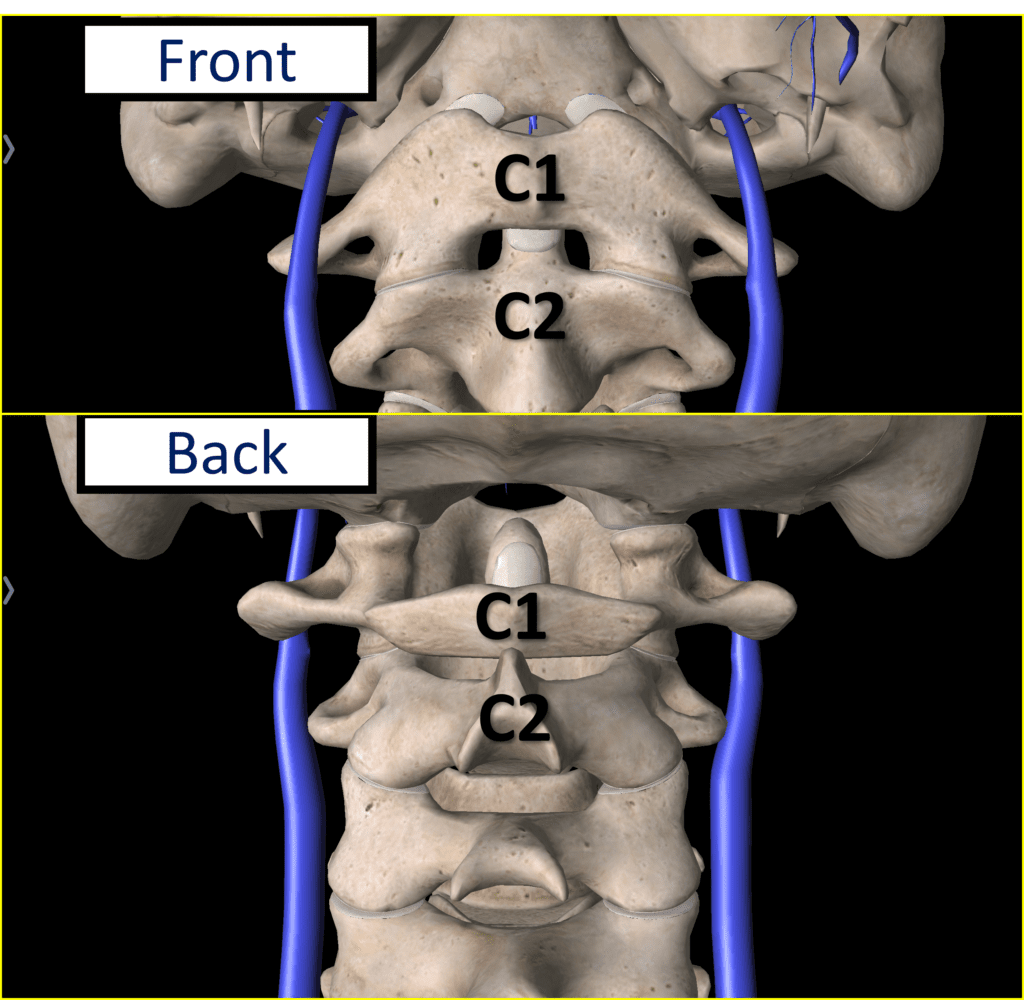

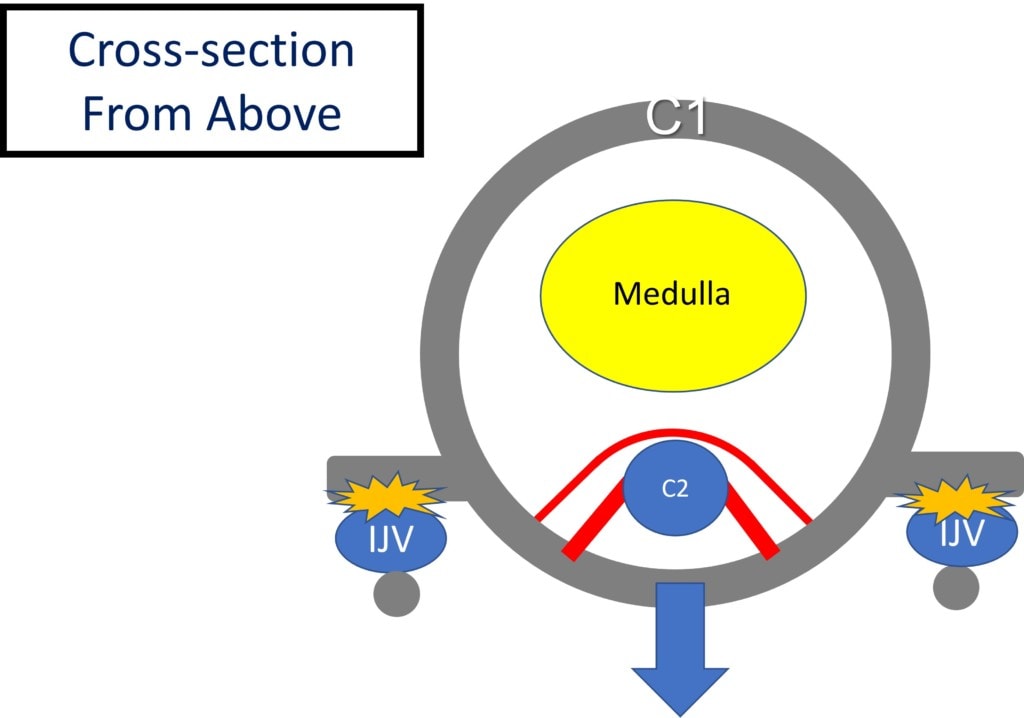

The internal jugular vein (IJV) is in the neck and lives in the carotid sheath which also contains the internal carotid artery and the vagus nerve. The IJV takes blood from the brain and in our context is important because it passes in front of the upper cervical spine as shown above. In fact, it passes right in front of the transverse process of C1. That’s the little side projection coming out of C1 and located just behind the vein as shown.

Above are front and back diagrams showing the relationship of the IJV (blue) to the C1 vertebra. Again note the proximity of the internal jugular vein to that side projection of the bone (transverse process also called “TP”).

Internal Jugular Vein Compression and CCI

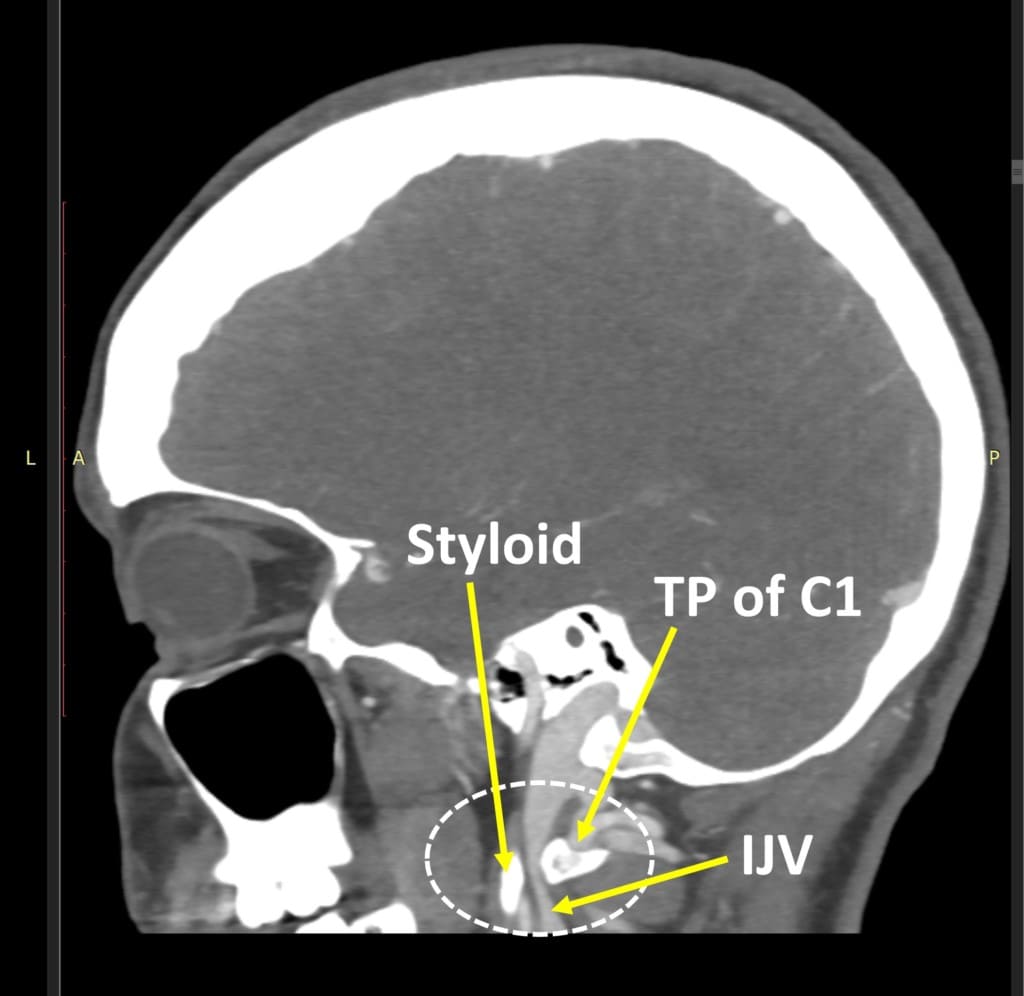

As shown above in a CT Venogram, the internal jugular vein can get compressed between the transverse process of C1 and the styloid. The styloid is a bone that comes from the bottom of the skull. Ligaments attach here which can become calcified, making this bone look longer on an x-ray.

Can Craniocervical Instability (CCI) Compress the Internal Jugular Vein?

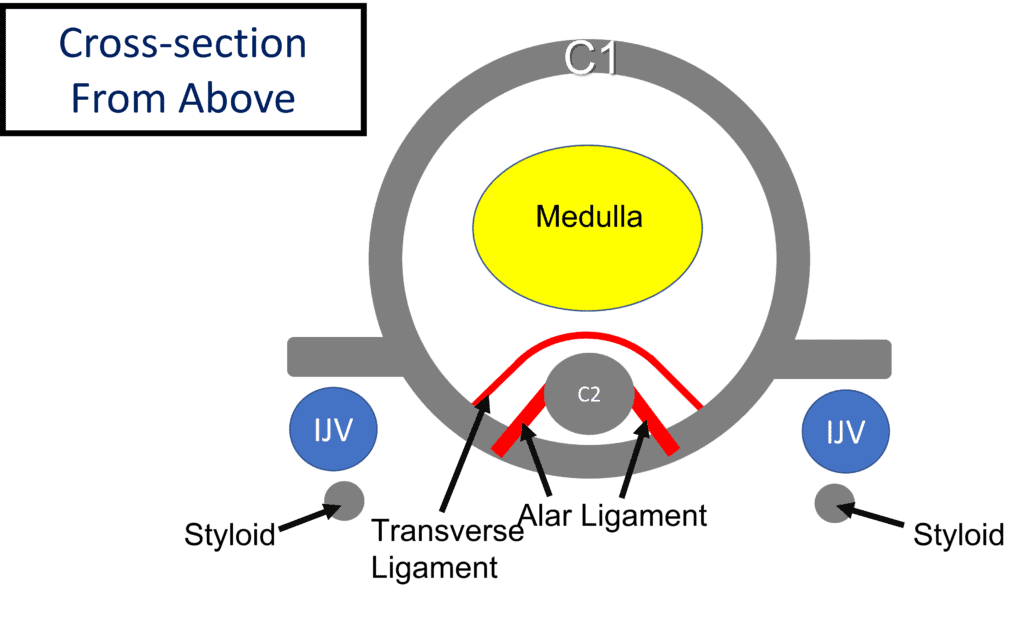

CCI or craniocervical instability means that the upper neck ligaments that normally firmly hold the skull to the upper cervical spine are loose, leading to too much movement (instability). Above we see that the little projections from the side of the C1 vertebra (TPs of C1) are just behind the IJV and sandwich that vein between themselves and the styloid. We also see ligaments in red (transverse and alar ligaments) which hold the C1 vertebra firmly to the dens of the C2 vertebra.

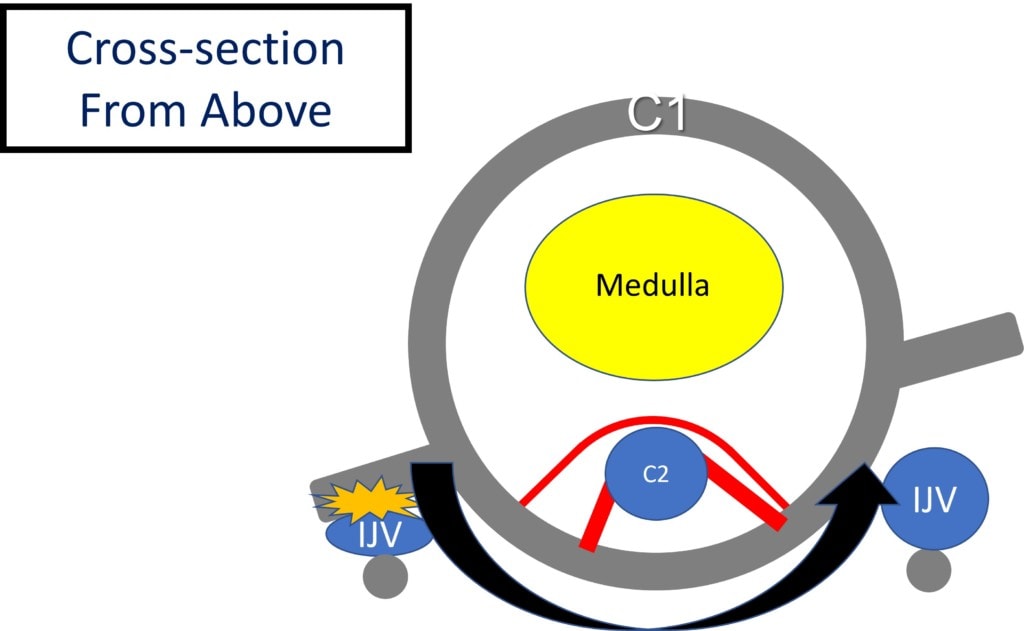

Above we see what happens when those ligaments are loose. The C1 vertebra can shift forward leading to internal jugular vein compression.

The same thing can also happen more on one side if C1 is rotated abnormally due to lax ligaments. How can that happen? See my blog on why C1 and C2 rotate on each other when the upper neck ligaments are lax.

What are the Symptoms of Internal Jugular Vein Compression and Intracranial Hypertension?

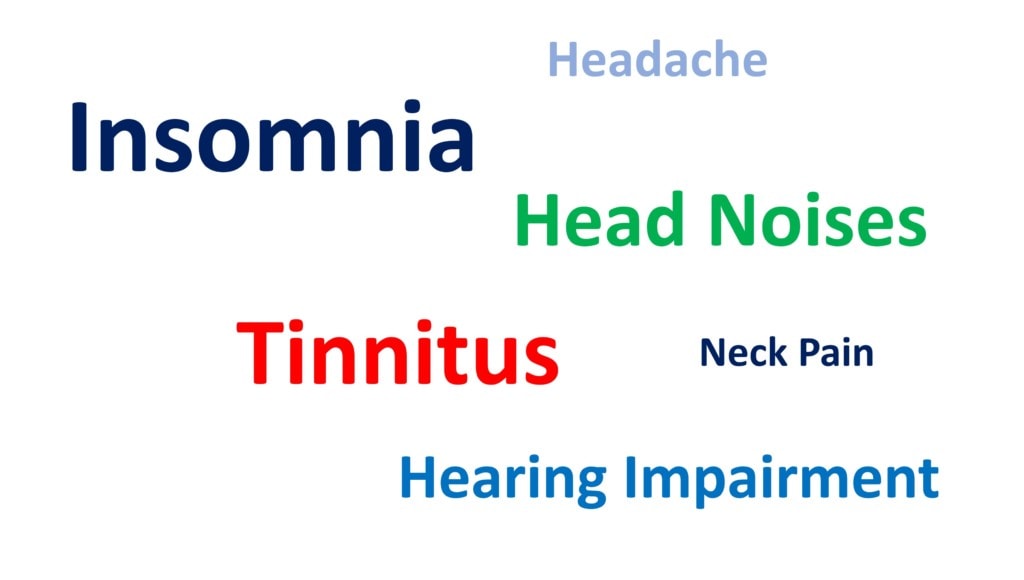

While there are many opinions about the symptoms that patients get when the internal jugular vein is compressed, let’s see what the research shows us. There is a study that was purposed to measure symptoms in known cases of internal jugular vein compression (1). I took the main table of results and turned that into the word cloud you see above. Here, the bigger the word, the more often patients with IJV compression complained of that symptom. As you can see, the top three symptoms were:

- Insomnia

- Tinnitus (ringing in the ears)

- Head noises (often a “whooshing” sound)

Then came hearing problems. Interesting, the two symptoms that many of my CCI patients believe are due to IJV compression (headache and neck pain) were the least commonly reported.

Diagnostic Testing to Rule Out Internal Jugular Vein Compression

This is where things get a bit complicated for patients trying to determine if IJV compression is causing their day-to-day problems. Why? As you’ll see below, there is no diagnostic test for this problem that’s 100% accurate in connecting the problem to symptoms.

To demonstrate the conundrum of IJV diagnosis, let me use a patient with a headache that’s believed to be coming from the upper neck. For example, we can see on a neck MRI that a specific facet joint is swollen and arthritic (let’s say C0-C1). We know from the research that the C0-C1 joint when painful refers its pain to the head. To nail down the diagnosis of the C0-C1 joint causing this patient’s headaches, we can then perform a diagnostic numbing injection under x-ray guidance with radiographic contrast. If that patient’s headache pain goes away after numbing the C0-C1 joint, then the pain is coming from that joint. If the headache doesn’t disappear, then the headache pain is coming from elsewhere. That’s called a “confirmatory block”. Basically, the idea is that we can numb any structure to confirm that it’s causing the pain.

No such “double-check” exists in the world of IJV compression. So if we think that the IJV is causing the headache, all we can do is to invasively treat the IJV compression to see if the headache goes away. Hence, all we have are diagnostic tests to see if the IJV compression exists, and then a best guess that this issue is causing the head symptoms.

CTA or CTV

A CT Venogram (CTV) is the diagnostic gold standard for IJV compression. A CTA (CT Angiogram) can also be used. These both involve injecting radiographic contrast into the blood vessels and then taking a CT scan, which is a 3D picture of the bones. This can be performed with the patient’s head and neck in neutral or with a head turn.

MRI and Ultrasound

While a specialized MRI (an MR Angiogram or MRA) can be performed, because of the longer times it takes to create the images and the poorer imaging of bone, this is not considered as accurate as a CTV. Finally, ultrasound imaging would have the least accuracy, as this is highly operator-dependent. Meaning if the ultrasound probe is off just a little bit, you can get inaccurate data about the IJV.

IJV Compression Treatment

IJV compression that involves CCI treatment comes in two main forms:

- Stabilize the CCI

- Open-up the IJV

Stabilize the CCI

If CCI is causing IJV compression, then stabilizing the CCI makes the most sense. While this can be done surgically (see this link to learn more about C1-C2 fusion surgeries to address CCI), fusion to treat CCI is a very invasive procedure with many possible life-changing complications. These days, a less invasive option is using your own bone marrow concentrate injected directly into the damaged and loose ligaments to help tighten these lax structures (PICL procedure).

Open-up the IJV

Opening up this area involves either surgically removing the styloid (styloidectomy) with or without shaving down the front of the C1 transverse process OR placing a stent to open up the IJV. Obviously, if you have CCI causing the compression, neither one of these makes much sense. First, both are big procedures. For example, both the styloid (through the stylohyoid ligament) and the transverse process of C1 (through the AO ligament) are involved in neck stability. Hence, the surgery to remove any of these structures will cause more neck instability in a patient who already has plenty of neck instability (CCI). The other option of stenting the IJV is unlikely to work, as the vein will just continue to collapse under the pressure.

Is Your IJV Compression Causing Symptoms?

This is a hard one for patients to understand, but critical in helping to keep them safe. A valid test is one that’s unlikely to be found in patients without symptoms and is only usually found in patients with symptoms (or the disease in question). Since the question here is whether the IJV compression is causing symptoms, then we should only very rarely find IJV compression in patients without symptoms. However, that’s NOT the case.

Take for example this recent study (2). The researchers wanted to determine how often IJV compression happened in patients without any symptoms. They did that by going back to look at CTA studies from patients who were usually being worked up for carotid artery stenosis. Meaning in these cases, finding IJV compression would be “incidental”. In other words, it would be just a random finding not linked to any IJV compression symptoms.

How often was random IJV compression without any symptoms found? Way too often for my comfort:

- Moderate stenosis was seen in 33.3%/25.9% (right/left) internal jugular veins.

- Severe stenosis was seen in 24.1%/18.5% (right/left) internal jugular veins.

- Severe bilateral extrinsic compression was seen in 9.3%

- The most common causes of extrinsic compression included the styloid process and the posterior belly of the digastric muscle.

This is a SERIOUS PROBLEM for the idea that we can use imaging that shows IJV compression to diagnose the cause of someone’s symptoms. You may be asking yourself, how is it possible that these patients had compression of the IJV without symptoms? One word provides that answer, “collateralization”.

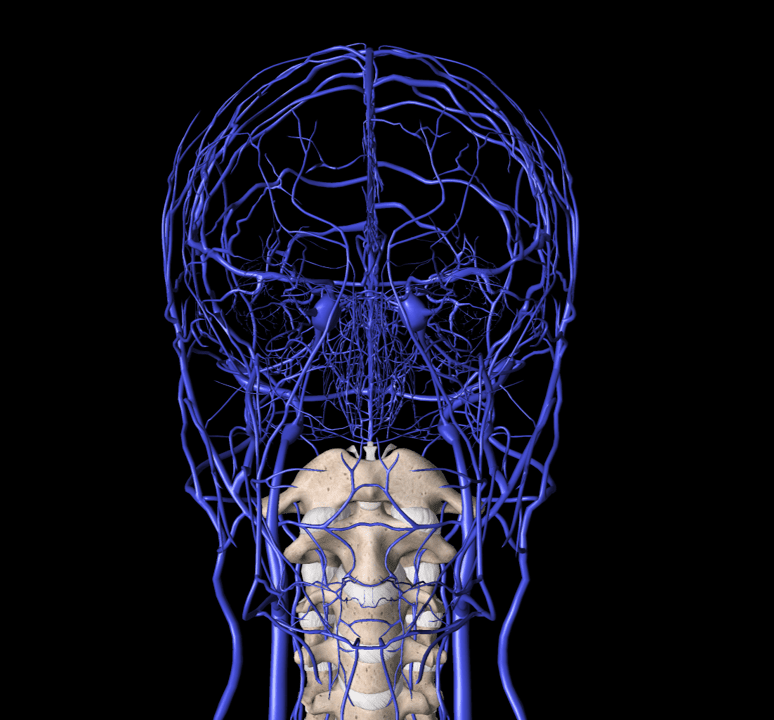

What is Collateralization?

Above my diagram shows just SOME of the venous routes out of the brain. As you can see, if one route is blocked, your body can enlarge another one. In addition, your body can also grow new veins around the compressed area.

If My IJV Compression and Intracranial Hypertension Aren’t Causing My Headache, then What’s the Cause?

There’s a long list of neck structures that if damaged or irritated can cause headaches. These include:

- C0-C1 facet joint

- C1-C2 facet joint

- C2-C3 facet joint

- Greater occipital nerve

- Lesser occipital nerve

- Third occipital nerve at C2-C3

- Third occipital nerve at posterior C2

- Superficial cervical plexus at the SCM

- Supraoribital and supratrochlear nerves

- Auriculo-temperoal nerve

- C2 dorsal root ganglion

- C2-C3 Disc

- Sphenopalatine Ganglion

- Many muscle trigger points

To learn more about each one, see my blog on a proper interventional spine work-up for headaches.

Putting It All Together

If you have CCI and think you may have IJV compression, realize that the first thing that needs to be done before invasive surgery is to stabilize your upper neck. In addition, if you have an imaging study showing IJV compression, that may or may not mean that this is causing your symptoms. Hence, we need to be cautious about using an image to drive very invasive procedures with possible big and life-changing side effects. Remember, the least invasive procedure that’s the most likely to work is always the right answer for the next step. To learn more about how that works, read this blog.

The upshot? IJV compression could be causing your symptoms, or it may have nothing to do with your symptoms. Like anything in medicine, a diagnosis comes from putting together all of the pieces of the puzzle including symptoms, hands-on physical exam, response to treatment, and diagnostic tests. A diagnostic test result by itself is meaningless unless viewed in the context of the bigger picture. In addition, even if IJV compression is causing some symptoms, fixing the CCI first makes the most sense.

__________________________________________________________________

References:

(1) Bai C, Wang Z, Guan J, et al. Clinical characteristics and neuroimaging findings in eagle syndrome induced internal jugular vein stenosis. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(4):97. doi:10.21037/atm.2019.12.93

(2) Jayaraman MV, Boxerman JL, Davis LM, Haas RA, Rogg JM. Incidence of extrinsic compression of the internal jugular vein in unselected patients undergoing CT angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33(7):1247-1250. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A2953

If you have questions or comments about this blog post, please email us at [email protected]

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.