Can You Use ChatGPT to Do Medical Research?

If you read this blog regularly, you know that I’m a big fan of AI and predict that it will change science and medicine for the better. However, as ChatCPT came into focus this past few months, several colleagues have claimed that you can now use it to do online medical research and generate text for medical research papers. Hence, I tried this out, but the results I got were initially concerning and, eventually, just possibly promising, but further analysis showed that I was being dangerously spoofed. Let’s dig into this topic.

AI Bots

ChatGPT is a project begun by OpenAI. Google Bard is a version of the same concept. Basically, you use large neural networks fed curated bits and pieces of the Internet. These machines try to guess what comes next as humans classify responses. The right answers strengthen certain neural connections in the software and weaken the wrong ones.

Both of these tools are a bit hyped right now, but as they evolve, there is no doubt that being able to have an AI do the grunt work of researching the medical literature will help medicine advance more quickly. For example, if an AI bot can accurately search the medical literature and draw conclusions from dozens or hundreds of references and cite references for how it got to that conclusion, scientists will be able to see connections between things in seconds rather than weeks of searching.

Colleagues Using AI to Write

Several colleagues claim they now use ChatGPT to help write introductions for papers or research various subjects. One claimed that this was transformative and saved him lots of time. Hence, I thought it was time I gave it a shot.

My AI Medical Research Quest

I’ve noticed that in some of my young CCI patients, there is evidence of osteophytes (bone spurs) in the craniocervical junction. Given that based on my medical experience, this would be otherwise rare to see; I wanted to research how commonly this is reported in normal young adults. Meaning if it’s rarely seen in otherwise healthy people in dedicated research studies, then it’s another sign of instability, as we know that bone spurs form in that spinal condition. If it’s more common than I thought, then maybe it’s just a random finding in my patients and not caused by their craniocervical instability.

My first deep dive was looking at this prevalence in the craniocervical junction. I struck out on initial PubMed and Google searches, took my colleague’s advice, and used ChapGPT and Bard. That proved useless, likely because there are so many terms for the craniocervical levels. Meaning you can call this the craniocervical junction, atalontoaxial, atlantodental, atlantoodontoid, etc… How poorly these services did with this request certainly piqued my interest, so I decided to narrow my search to one spinal level at C2-C3 and compare and contrast results.

The question, which I phrased in several different ways, was simple. Write a short scientific paper on the prevalence of bone spurs (osteophytes) at the C2-C3 compared to other levels of the neck.

From decades of reading the medical literature, reading thousands of MRIs and CT scans of the cervical spine, and half a lifetime of being a doctor, I know that the correct answer is that there are far fewer bone spurs in the upper neck at C2-C3 when compared to lower cervical levels (like C5-C6 for example where they are common by middle age).

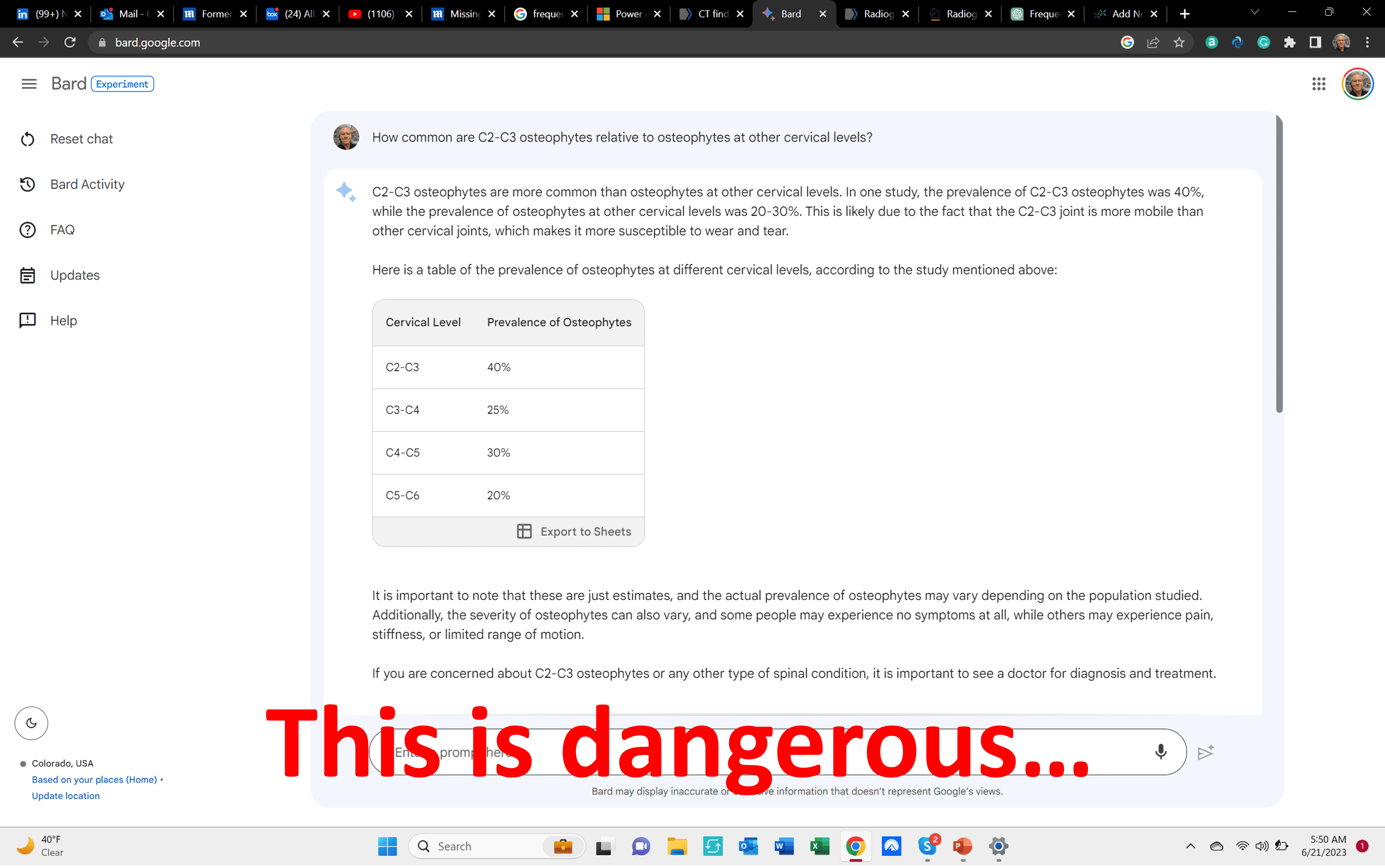

I first tried Google Bard:

What I got back was very dangerous. Why? Bard created an entire table that looked authoritative that compared the prevalence of osteophytes at various spinal levels. As you can see above, at C2-C3, it pegged the prevalence at 40%, which was higher than the percentage reported for C5-C6, the most likely level in the spine at which to find bone spurs. Near as I can tell, it made up this table or pulled these numbers from some random source out of context.

Next up was ChatGPT:

This isn’t dangerous but is just a paragraph of meaningless garbage regurgitated onto the page. It references a study that didn’t even include the level asked about, which was C2-C3.

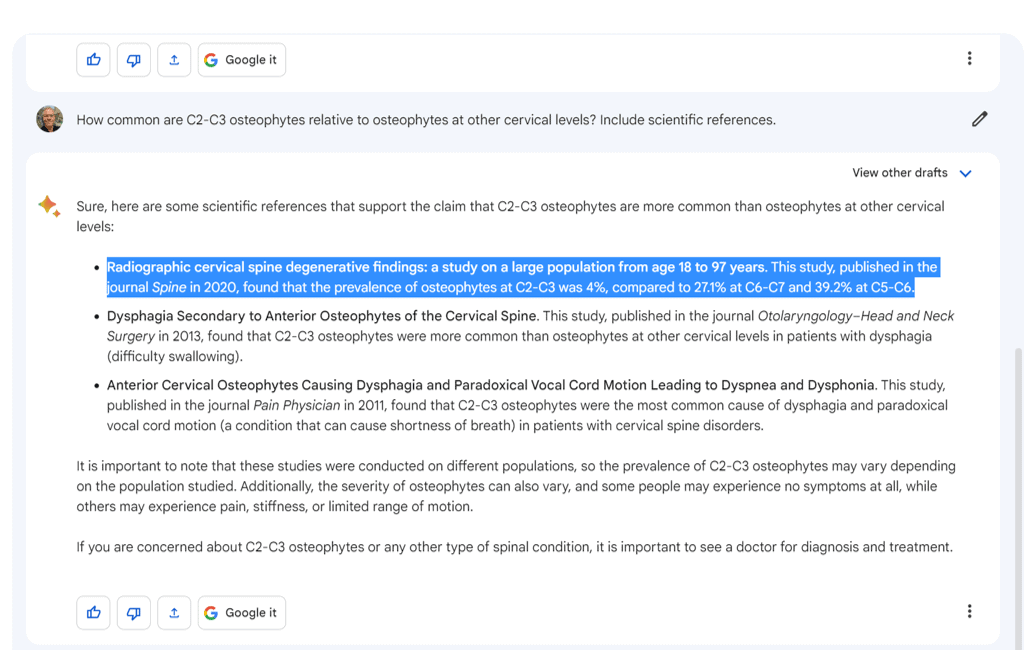

Next, I went back to Bard and rephrased my question by asking it to include scientific references:

Here I got three studies back, one on point (highlighted above) and two that had nothing to do with my question. These two were focused on how C2-C3 osteophytes impact swallowing. So I would say this is maybe marginally better than a simple Google search because I found a new study to read.

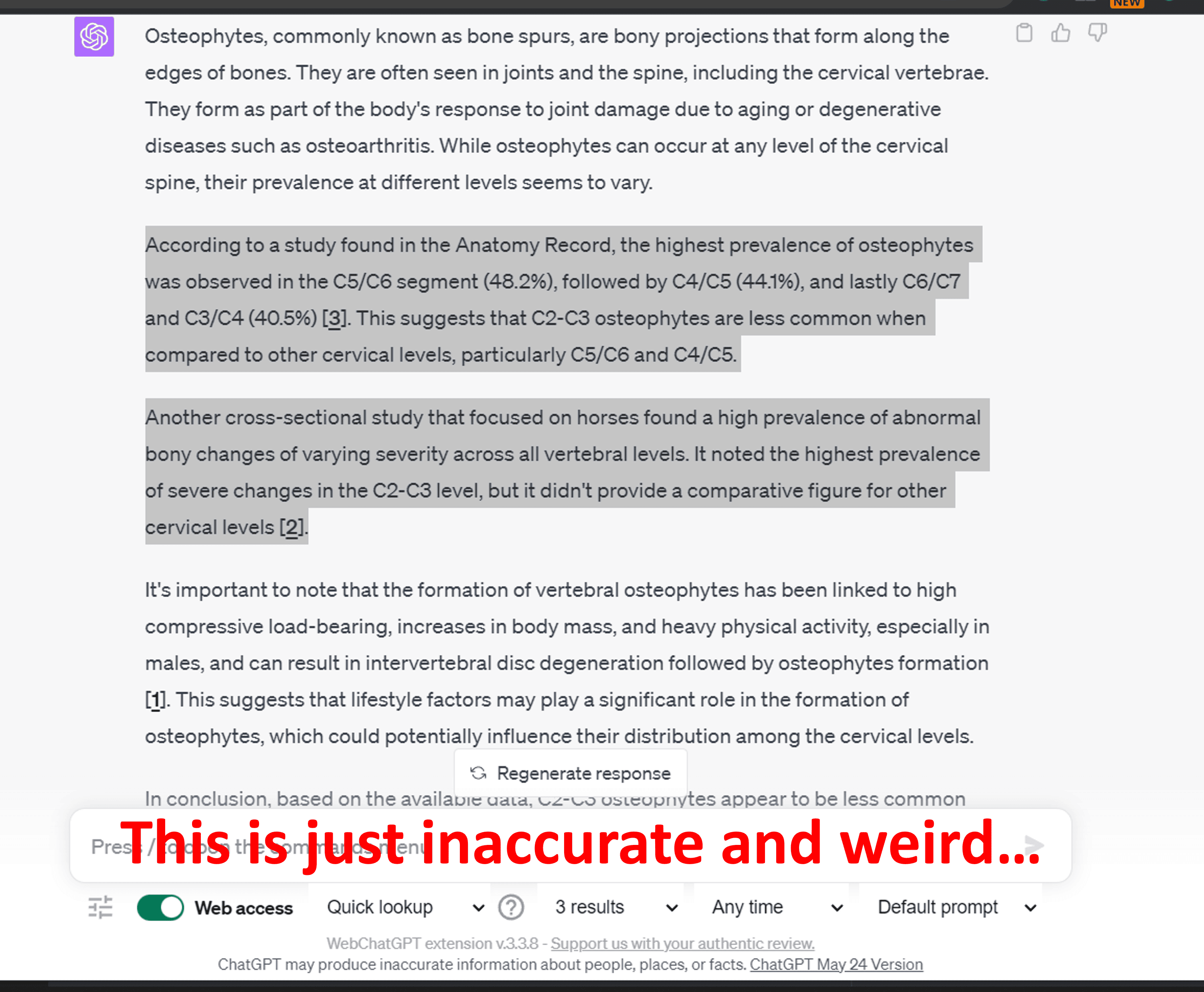

Finally, I returned to ChatGPT after upgrading from the old 3.5 version to the new 4.0. This is what I got back:

The first paragraph I highlighted cites a study that never looked at the C2-C3 level and drew a conclusion that this level had fewer osteophytes without cited evidence. The good news is that the guess is correct, but ChatGPT can’t reference how it got there. The second paragraph is just plain bizarre because it includes a horse study. That may make some sense, as I never told it to include only humans. Next, I asked ChatGPT 4 about relative prevalence and made sure it knew that I was only talking about humans. Here’s the result:

That got rid of the horse study, and again, it guessed the right answer, and at least now it recognized that it didn’t have the research citations on the prevalence of osteophytes at the C2-C3 level.

I then returned to Bard and asked the same question I had asked before: “How common are C2-C3 osteophytes relative to other cervical levels? Include scientific references.” Like the second response from ChatCPT 4, it was much better:

This Bard response is what I would have expected a fellow who was given this assignment to return with. However, these references that Bard cited, near as I can tell, don’t exist! They seem to be entirely made up.

Why did both AI services improve with repeated questions? Could it be that I was the only human on earth to ask this question since these AI tools were created? That’s possible since expertise in CCI is limited to under a dozen individuals worldwide. My best guess is that both were learning as I asked these similar questions. Bard seems to have caught on quicker than ChatGPT 4, but as reviewed above, it got there by manufacturing research citations.

The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly

In the end, the answers are all scary bad. For example, if a patient or young physician had gone with the table claiming that the prevalence of bone spurs at C2-C3 was 40% and declined as you went down in the neck to lower cervical levels, that would have been backward misinformation. Or if you relied on the references in the final Bard answer, you would have relied on information that doesn’t exist. Hence, I would not trust either service to perform medical research.

The upshot? These will be fantastic medical research tools as they evolve over the next few years. This will increase the pace of medical innovation as these services get more accurate than humans and can sort through hundreds of medical research papers to draw accurate conclusions in seconds. However, at this point in their development, I would be very cautious about using them to research anything medical.

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.