CCJ Instability: Patients Don’t Know What Their Doctors Don’t Tell Them

If you read this blog, you know that I often write about what I see every day in practice and usually about those things that, as my mother used to say, “get me going.” This week I evaluated a young woman with CCJ instability who didn’t know before getting her neck fused and nerves surgically removed that she hadn’t tried every conservative-care option. I see this all the time, and it’s disturbing that people are pulling the trigger on life-changing and irreversible care options, like neck fusion, before they have tried everything that’s less invasive and that might help. Let me explain.

What Is CCJ Instability?

The CCJ is the high upper neck, and the acronym stands for “cranial cervical junction.” This is basically where the head meets the neck. There are strong ligaments here (alar, transverse, accessory, apical dens, and others) that hold your head on, and when they become injured, the CCJ can become unstable, which just means that the head moves around too much on the neck. Given that it’s basically a 10- to an 11-pound bowling ball, that can mean that the joints, tendons, muscles, nerves, and ligaments can get irritated or torn up and become painful. This can result in headaches, dizziness, feeling “out of it,” facial symptoms, heart racing, and or other miscellaneous random symptoms elsewhere in the body.

These ligaments can become damaged by trauma, such as a car crash, hitting the head against something, or other events. In addition, some patients are born with stretchy ligaments (Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, or EDS), and as such, many joints are unstable, including the CCJ. Finally, sometimes it’s unknown what caused the issue.

CCJ Treatment Options

If the ligaments are damaged, it’s unusual that exercise therapy alone helps. In fact, many of these patients flare up with active strengthening therapy. Many patients can get relief with low-force, chiropractic manipulation delivered by an upper-cervical specialist. Some can be managed this way. Curve-restoration-type chiropractic therapy (CBP) can also help. Other patients find one of the few true expert PTs out there who know how to reposition the upper neck joints when they get out of place. Finally, some end up trying prolotherapy, which is a type of injection that can tighten loose ligaments, but the issue here is that this therapy can’t reach the ligaments discussed above. Hence, the main problem is never directly addressed. Finally, many patients get bounced around from specialist to specialist and try all sorts of medications and then eventually make their way to one of the few orthopedic or neurosurgeons who perform upper neck fusions (CCJ fusion surgery).

Finally, we have developed a new procedure that can access these ligaments so that we can inject substances that can heal them. For more information, see my video below:

CCJ Fusion Surgery

One of the more risky neck surgeries in existence is CCJ fusion surgery. Why? The surgeon places long screws and/or plates to bolt together the upper neck joints. There is much that’s critical in this part of the neck, including the vertebral artery that supplies the back of the brain, many important nerves, and, of course, the upper cervical spinal cord.

While I have seen one patient who had a severe enough problem (she was unable to be upright for more than a few minutes) where she dramatically benefited from this procedure, I have also seen my share of disasters. Take, for example, a college student where one of the screws was placed too far and into the C0–C1 facet joint, causing that joint to become destroyed and beyond our ability to help. Or patients who have had to have several surgeries, each one removing more and more critical upper neck structures. Or patients who took the myriad risks and dodged the complications bullet, but who are no better or who develop new problems from the surgery.

The Biggest Issue with Fusion Is ASD

When a doctor fuses one level in the spine, the adjacent levels get more wear and tear. Sometimes that results in the adjacent levels wearing out at a much faster rate. This is called adjacent segment disease, or ASD. To understand more, see my video below:

Some patients find that one pain is better, but a new painful area crops up. Basically, the pain that improved was the one that was being caused by the instability (which is gone because the area can’t move), and the new pain that crops up is caused by the ASD.

The Single Biggest Treatment CCJ Patients Miss That Can Help Them Without Getting an Invasive Fusion

The upper neck has joints just like the rest of the neck. Neck joints are usually called “facets” by most physicians. A more obscure medical term is a zygapophyseal joint, or “Z-joint.”

The upper cervical joints are the C0–C1, C1–2, and C2–C3 joints. These upper neck joints are all shaped differently than the lower neck joints and hence allow for different types of motion. The C0–C1 joint allows the head to nod on the neck, the C1–C2 joint is involved with half of your neck rotation, and the C2–C3 joint is one that allows a bit of both.

Neck joints can become injured with trauma or wear and tear and are one of the things that can cause neck pain and headaches. The upper neck joints in particular, when they have problems, can cause headaches, dizziness, and/or cognitive problems, like feeling “out of it.” In addition, the upper cervical joints often get overloaded and beat up in patients with CCJ instability.

Hence, injecting the C0–C3 facet joints to see if they are causing symptoms in patients with CCJ instability just makes common sense. However, there’s a catch. Most physicians have little experience in injecting these joints, especially C0–C1 and C1–C2. In addition, because the precision needed to inject these joints is higher and the risks are slightly higher, most doctors have never learned how to inject them. Finally, the push by interventional pain doctors to drop facet joint injections (which insurance companies reimburse less for) and move toward burning nerves to help pain (radiofrequency ablation [RFA] which insurers reimburse better) has meant that most doctors now want to burn nerves instead of injecting facet joints.

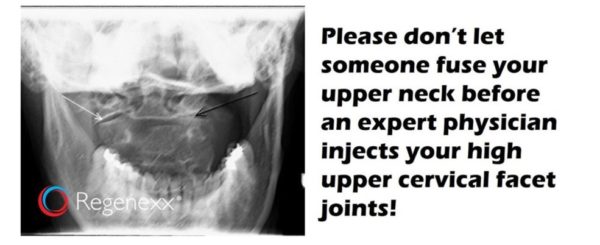

Because of all of this, we tend to see patients who have never had the C0–C2 joints injected to determine if these are causing some or all of their symptoms. In fact, this problem is made worse by the fact that only about 100 US physicians have any significant experience with injecting these high upper cervical joints. That leads us to my patient discussed above, who got her CCJ surgically fused (which didn’t help her symptoms), but somehow never got these joints injected.

Beware of Faux C0–C2 Injections

Last week I was corresponding with a different patient, who has yet to get surgery but who believed that a physician in Chicago performing prolotherapy injections had injected the C0–C2 facet joints because that doctor was using fluoroscopy (real-time X-ray imaging). Regrettably, I had to inform him that the doctor never actually injected these joints.

This ruse is common, so make sure you don’t fall for it. Some doctors who perform prolotherapy (injections to tighten lax ligaments) use a C-arm unit or ultrasound imaging to guide their procedures. This is great, as it’s a step up from blind prolotherapy, but there’s a huge gulf separating how these doctors use imaging guidance and an actual facet injection delivered by an expert interventional spine physician.

Prolotherapists who use guidance like a C-arm tend to use it merely as a way to identify the bony landmarks where their needle should touch down before injecting. Interventional spine physicians have much more training and use the device to make sure the needle is placed into the joint and then inject a contrast agent that can be “seen” on X-ray to ensure that the injection is really in the desired joint. While these two things seem similar, they require vastly different levels of training. For example, you can train a doctor to use fluoroscopy to place a needle on a bony landmark in the spine in minutes. Training a physician how to confirm contrast spread inside neck facet joints takes weeks to months. It’s just that much more difficult as in the latter injection, you need to hit a target millimeters wide that is often inches deep. Finally, training a physician to inject the high upper cervical joints takes even more time.

We are lucky enough, because of the number of patients we see with these issues, to have injected thousands of C0–C1 and C1–C2 joints. We’ve also published on new injection techniques to make the notoriously difficult C0–C1 facet joint more reliable. We generally also know where the physicians who have a higher level of experience injecting the high upper cervical spine are located. The video below is on that new C0–C1 injection technique:

What You Inject into Facet Joints Matters

Most facet joint injections are with high-dose steroids and toxic anesthetics, which harm the cartilage in the joint. We’ve used cartilage-friendly ultra-low-dose steroids and ropivacaine for years, and this provides equal relief to the shots that harm the joint. Finally, we also commonly use platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and stem cells in facet joints, which can help repair damage.

The upshot? It’s nuts that we have patients getting high-risk CCJ fusions before everything else possible has been done. In addition, it’s also crazy that so few physicians know how to inject these upper neck facet joints and that some patients think they have had these procedures, but have never had anything close. Hence, if you have CCJ instability, make sure that you find one of the few physicians in the country that has experience injecting these joints!

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.