A Pain Reprogramming App and a New RCT

There’s been a decades-long dispute between pain psychologists and physicians that treat chronic pain. These past 5 years, the concept that the chronic pain you experience can be cured through talk therapy has expanded like a forest fire in a Santa Ana wind. Now new research aims to prove that this talk therapy works. In addition, this new program called PRT also comes with an iPhone app. Let’s dig in.

Biopsychosocialists

Everything we’ll review this morning fits into a model of chronic pain called “Biopsychosocial” (BPS). What this camp of pain psychologists believes can be described simply as:

-Because doctors talk about the bad things that can happen due to damaged tissues, we make people sicker.

-If doctors just told patients with chronic pain they will be fine, the world would be a better place.

As you might imagine, in some ways, this idea is diametrically opposed to physicians who perform procedures to help chronic pain patients. Hence, this sets up an interesting dynamic between psychologists who espouse this point of view and physicians who will buy the idea for some patients, but who don’t believe that most of their patients in pain fall into this category

My History with “The Pain Is All in Your Head” Concept

As a young doctor in the 90s, the “pain is all in your head” industry was peaking in my community. In fact, there were multi-disciplinary rehab programs costing tens of thousands of dollars a week that sought to help chronic pain patients restore their lives. These were called “Chronic Pain Programs”.

The idea was that since an MRI couldn’t find out why you hurt and the doctor treating you didn’t understand that either, the pain was largely in your head. Hence, teams of physical medicine doctors, pain psychologists, physical therapists, and occupational therapists worked with a patient for 8 hours a day, often for weeks. The results? Patients felt better and became more active for a while, but after 6 months to a year, they were right back to being high utilizers of medical care. Hence, by the early 2000s, these expensive programs were deemed by insurers to not be worth the money and they withered away.

The Pain Is Now All in Your Neural Pathways

After the Chronic Pain Program concept died, the good news is that it was replaced by an explosion in knowledge about what was causing pain. This largely stemmed from both groundbreaking basic science research and newly founded interventional pain practices that were able to identify exactly where the pain was originating. Simple things like epidural steroid injections, facet injections, and nerve blocks could help identify what was wrong and often provide relief.

About 5-10 years ago, we began to see a new concept emerge. This has many names including PNE (Pain Neuroscience Education), but the idea is the same as a chronic pain program. However, this time, the pain isn’t in your head, it’s in your neural pathways. Meaning, you can be trained to ignore pain signals. These signals are like a stuck switch and if you just ignore the result of the switch, you’ll fix yourself. It’s basically a therapeutic extension of the BPS model.

While there are certainly patients that could benefit from this idea, all of this took on a religious zeal that always makes me uncomfortable. In addition, given my experience with the poor results of pain programs from the 90s which had a full-court press approach of armies of therapists working with pain patients, I remained skeptical.

Prior PNE Study Problems

The PNE research has always suffered from the same problem as all research on this topic. Basically, if someone has chronic pain, you first have to decide if they have a legitimate reason to be in pain or not. The problem is that the people that run these programs (physical therapists and psychologists) don’t have any access to the type of interventional spine block studies that would determine if someone had a damaged facet joint or irritated nerve despite a benign-looking MRI. Hence, all of these studies start behind the curve with diagnoses like “chronic low back pain”, which isn’t really a thing. In fact, that’s like performing a chemotherapy study by saying the patient has “cancer”, but not delineating one of the hundreds of types of cancers that can impact specific tissues.

The other major problem in PNE studies is the placebo effect itself. Meaning, the more time you spend with someone doing something that they have been told will reduce their pain, the more likely they are to report that their pain is less. Some of this is true placebo (they believe they’re better so they are) and some of it is the patient molding themselves to expectations. Meaning, they know from the nature of the talk therapy that the right answer is always “I’m in less pain”.

This last part is a real sticky wicket. Meaning a study on this type of talk therapy would have to have an equal amount of time spent speaking to patients with one script being treatment and the other being mostly gibberish, both about how to lower your pain levels. Why? Again, more attention equals more placebo effect. In addition, more expectation of lowered pain levels after the therapy means lowered pain level reporting.

The problem? The psychologists that publish in this area always compare a high-intensity therapy group to a group that receives little therapy. Meaning, these studies begin with a fatal flaw.

The Recent RCT

The recent study was published in JAMA Psychiatry and studied the effectiveness of pain reprocessing therapy [PRT] (1). This is what the authors say about PRT:

“We developed pain reprocessing therapy (PRT) based on this understanding of primary chronic pain. Leading psychological interventions for pain typically present the causes of pain as multifaceted and aim primarily to improve functioning and secondarily to reduce pain. PRT emphasizes that the brain actively constructs primary chronic pain in the absence of tissue damage and that reappraising the causes and threat value of pain can reduce or eliminate it.”

So basically, PRT is the same as PNE. The MRI doesn’t show why you’re in pain, hence there is no tissue damage. This basic concept has been proven wrong by many different studies using diagnostic blocks including seminal work by Wallis in traumatic neck pain (2). However, we’ll pretend those studies don’t exist for the purposes of this deep dive.

In this study, the authors conclude that PRT is highly effective, so let’s take it all apart. The researchers randomized patients with 4/10 back pain or more into three groups:

- Eight one hour PRT therapy sessions two times a week for one month (n=50)

- Watching two videos on placebo injections and then getting a subcutaneous placebo injection with saline (n=50)

- Usual care (n=50) (i.e. no talk therapy)

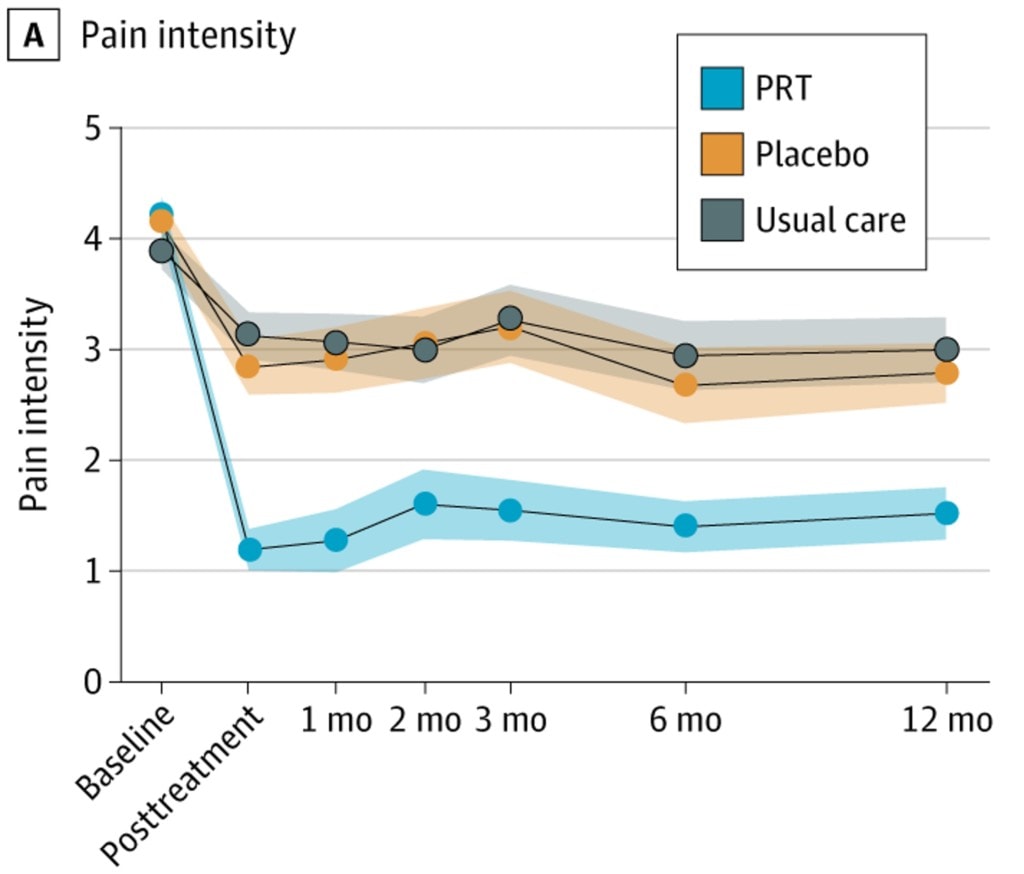

This Numeric Pain Score graph sums up the results:

All groups had low-level back pain at the start, and the PRT group had pain that went from 4/10 to about 1-1.5/10. The two other groups had pain that went from about a 4/10 to about 3/10. At first, that looks very impressive, but is it?

This study has more holes than Swiss cheese. So what are the issues?

A Better Placebo Effect

Again, the concept of a placebo is that because of time and attention and a belief that the therapy will be effective, the patient imbibes this concept and improves. Because of the attention and expectation effects I reviewed above, for this to be a valid study, you would need the following groups:

- Eight one hour PRT therapy sessions two times a week for one month

- Eight one hour therapy sessions two times a week for one month that didn’t deal with the same issues as PRT and was gibberish, but that the patient was told would help their pain

Why do it this way? Because remember, attention and expectation cause a placebo effect. Hence, the attention between the groups has to be the same. In addition, both groups need an expectation that talk therapy will make them better.

However, here, in the PRT group, we required 50 patients to get two one-hour talk sessions a week which is lots of attention. Then the other group got two videos to watch and a single placebo back injection (not much attention as this is only one visit with a provider versus 8 in the PRT group). Finally, one group got no attention at all.

Hence, we would expect the placebo effect in the PRT group to be much higher than the placebo effect in the other two groups. Indeed, that’s what happened. Not doing anything but injecting the skin in the back once caused a 25% reduction in pain long-term. So did simply enrolling the patient in the study and ignoring them. Hence, we would we expect a bigger effect from spending a huge amount of time with a patient using a talk therapy that is supposed to end their pain.

Brain Imaging Findings

Clearly, if there’s one aspect of this study that conclusively proves that PRT works, it’s the fancy brain imaging studies they performed! These guys went all out and used very sophisticated fMRI studies and saw more positive changes in the brain in the PRT group! That surely must mean PRT is crazy effective? Nope. Why?

We know from other studies that if you had a better placebo effect, the research is quite clear, you will see more positive brain-related changes on functional MRI (2-4). Meaning all of these things observed as brain changes caused by the therapy have also been observed in patients experiencing a placebo effect. So much for the millions spent on brain imaging.

No Diagnosis

The classic pain psychology study, as above, never takes the time to perform standard of care block studies to determine what the diagnosis was. Meaning, there is no such diagnosis in 2021 as “chronic low back pain”. For example, was it the facets causing the pain? An irritated nerve? How about a disc? Nobody in this study took the time, energy, or effort to find out. Hence, were these patients with real diagnoses or hand-selected to be those patients overly focused on their disability? There is no way to tell.

Who Funded This Study?

The lead author is also involved in a start-up called “Curable Health” which uses an app to deliver PRT services. So he has a financial stake in PRT being effective. That by itself doesn’t mean the study is bad, but it’s interesting.

Also, buried deep within the study appendices are several funders. One is a group called “The Foundation for the Science of the Therapeutic Encounter”. They believe firmly in the placebo effect (which is good as that’s what was most likely detected here). Another is the “Psychophysiologic Disorders Society”. This is a group that believes in what PRT is preaching.

Using the Curable App

As I exposed above, this study is really a commercial venture proof of concept study for an app called “Curable”. Does that app work? I’ll try this app on about a dozen tough patients over the next few months to find out. Will it be as effective as the funders of the study claim? Only time will tell.

Should You Try PNE or PRT?

The short answer is that there is no harm in trying these therapies. Because PNE has been out there and is widely used by physical therapists, it’s widely accessible. On PRT, you can buy the Curable app for $4.99 a month and give it a whirl. Will it work? Let me know.

The upshot? On the surface, this study seems effective but has the same fatal flaws as every other pain psychology study. However, in the end, if you want to try PRT, give the Curable app a whirl and let me know how you do!

_______________________________________________________

(1) Ashar YK, Gordon A, Schubiner H, Uipi C, Knight K, Anderson Z, Carlisle J, Polisky L, Geuter S, Flood TF, Kragel PA, Dimidjian S, Lumley MA, Wager TD. Effect of Pain Reprocessing Therapy vs Placebo and Usual Care for Patients With Chronic Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021 Sep 29. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2669. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34586357.

(2) Wallis BJ, Lord SM, Barnsley L, Bogduk N. The psychological profiles of patients with whiplash-associated headache. Cephalalgia. 1998 Mar;18(2):101-5; discussion 72-3. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1998.1802101.x. PMID: 9533607.

(3) Wager TD, Atlas LY. The neuroscience of placebo effects: connecting context, learning and health. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(7):403-418. doi:10.1038/nrn3976

(4) Wager TD, Rilling JK, Smith EE, Sokolik A, Casey KL, Davidson RJ, Kosslyn SM, Rose RM, Cohen JD. Placebo-induced changes in FMRI in the anticipation and experience of pain. Science. 2004 Feb 20;303(5661):1162-7. doi: 10.1126/science.1093065. PMID: 14976306.

(5) Elsenbruch S, Kotsis V, Benson S, Rosenberger C, Reidick D, Schedlowski M, Bingel U, Theysohn N, Forsting M, Gizewski ER. Neural mechanisms mediating the effects of expectation in visceral placebo analgesia: an fMRI study in healthy placebo responders and nonresponders. Pain. 2012 Feb;153(2):382-390. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.10.036. Epub 2011 Dec 2. PMID: 22136749.

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.