Is Saline a Placebo or a Treatment?

Credit: Shutterstock

In the world of pain and arthritis research, it’s been a long-held belief that the gold standard is a placebo group that receives saline. However, these past 5-10 years there’s been pushback on that idea by the research community. Meaning many now believe that saline is a treatment by itself. Hence, what if saline isn’t a placebo? That would turn the research and FDA drug approval world on its head. So let’s dig into this topic as it’s a big hairy issue for both researchers and patients.

A Quick Detour

For those of you who follow this blog, you know that I usually write between 5 and 7:30 am almost every day. Why? Because many times, it forces me to go beyond just reading a research abstract. It allows me to personally deconstruct the research myself.

As a busy physician with a medical practice and someone who is also responsible as a medical director for a large provider network and who also manages clinical and lab research, if I don’t take time to slow down when nobody else is awake and dig deep into 10-20 topics a month, I could never stay on top of the fire hose of new research in my field. As is, even with spending an extra 40-50 hours a month diving deep into new research sometimes it still feels like all I can do is to take gulps out of the torrent of research flying by. Hence, this topic is one that I’ve wanted to explore for years and am now just getting around to it.

What Is a Saline Placebo?

The idea of a placebo study is at the core of modern drug and procedure research. The idea is really simple. You take something you want to test and give half the patients that thing (i.e. a new drug or procedure) and then you randomly give the other half a placebo which is a fake treatment. The goal is to get rid of what’s called the “placebo effect”. Meaning that some patients react positively to treatment just because of the act of getting treated, not because the treatment works. Hence, if your new drug or procedure works better than a faked placebo treatment, that new therapy is effective.

Saline has long been considered the gold standard of placebos. In studies where a drug is delivered intravenously or otherwise injected into the body, saline is used as a placebo control because it’s believed to be inert. Hence, since the 1950s, a HUGE number of studies have been performed with a saline placebo group.

What if Saline Isn’t a Placebo?

Saline turning out not to be a true placebo is like us finding conclusive evidence that the world is really just a computer simulation like the Matrix and we’re all really sitting in a room someplace hooked to a master computer. It would blow so many medical research minds that its impact is hard to accurately describe. Suffice it to say that decades of FDA-supervised drug trials would have to be scrapped. Why?

Most drugs that fail to make it to the market, fail because they couldn’t beat the placebo control. For every drug that makes it past that gauntlet, dozens never do. Hence, if saline turns out to be an effective treatment rather than an inert placebo, thousands of drugs that were turned down would have to be reconsidered.

How Could Saline Be a Treatment?

Saline is just saltwater that’s the same concentration as your body’s natural fluids (or the ocean). How in the world could saline be an effective treatment? That makes no sense, right? Not exactly.

Let’s take knee arthritis, which is the subject of this morning’s deep dive. We know that one of the driving factors in this disease is a toxic witch’s brew of chemicals in the joint fluid. These inflammatory chemicals break down cartilage and cause swelling (1). Saline could dilute these chemicals, making them less concentrated and less able to cause problems.

The Research Showing that Saline Is Not a Placebo

After my recent blog post on how amniotic products were failing to best placebo in knee arthritis studies, a physician colleague posted a link to an article that showed that saline, according to a 2016 meta-analysis, wasn’t really a placebo, but a treatment (2). In fact, this was the conclusion from that paper:

“Pain relief observed with IA saline should prompt health care providers to consider the additional effectiveness of current IA treatments that use saline comparators in clinical studies, and challenges of identifying IA saline injection as a “placebo.””

I had seen this concept presented or mentioned a few times at conferences. In fact, the lead author of this paper is a knee arthritis researcher who has been bitten several times by the drugs he tested failing to squash saline.

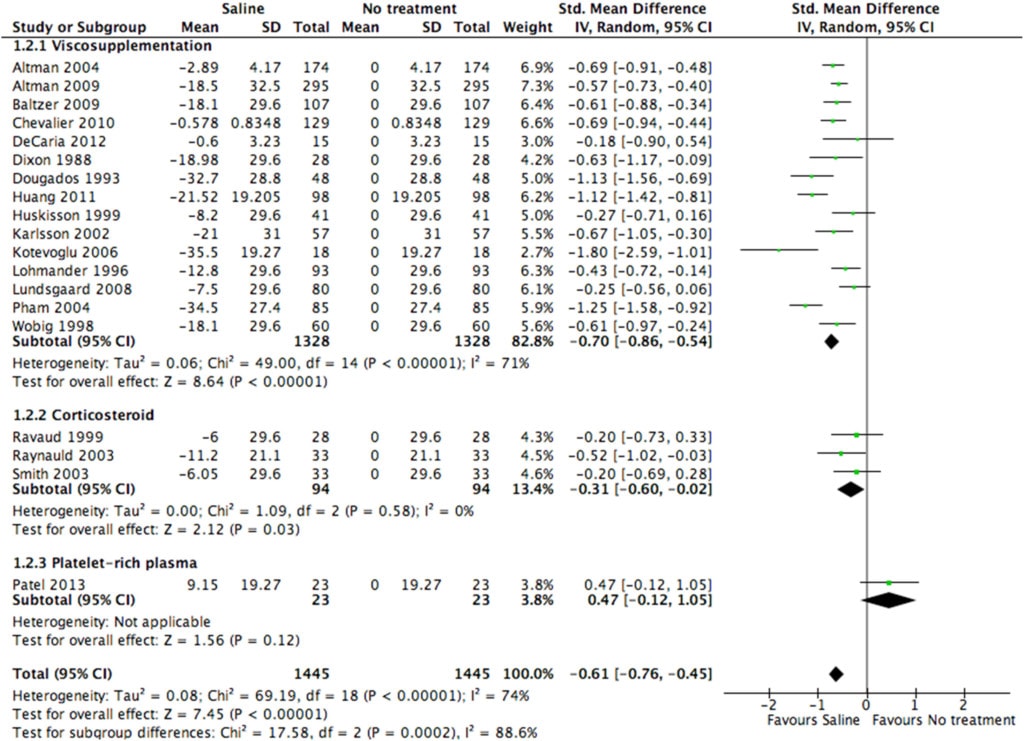

Digging into this paper is difficult, as even for me, someone who has a few dozen scientific publications, it was hard to decipher. In fact, the graph below stayed on my computer for more than a week, just staring at me. It’s either a statistical tour de force or way too complex:

It took me a few times reading it and the paper to get a sense of what was being portrayed here. This is the relative impact of saline versus no treatment. Meaning the authors are trying to prove that saline has a treatment effect. The problem with this and the whole paper, in fact, is that they never tell us how big a treatment effect saline has, instead they always couch that effect as relative to something else.

Why Knowing the Size of the Saline Treatment Effect Is Critical

One of the things that gets lost in clinical research studies is the difference between statistically significant effects and clinically significant ones. In fact, this quote from Mark Twain is important for understanding this concept:

“There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.”

Meaning, a treatment being tested can be statistically different in a study, but clinically meaningless. Take for example a study of a new drug that shows that it’s statistically better than a placebo. That’s merely a math concept that means that the amount it was better is very unlikely to be due to chance. However, if the drug only showed 10% improvement, most doctors and patients would say that it’s clinically useless. Hence, in this example, the effect of the drug was statistically significant, but not clinically significant.

Hence, when I read the saline placebo paper, I was concerned that at no time, did the authors tell us how clinically significant saline was or wasn’t. Everything was couched in statistical math and not clinically real statements. Hence, it was time to dive deeper to find this info.

Clinically Significant?

To get an idea of big these saline treatment effects were, I reviewed the bibliography for the study. There were two of the references that had full-text PDFs that didn’t live behind a paywall, so those are the two I chose (3,4). Both used the WOMAC functional scale. What’s that?

WOMAC is a functional questionnaire that measures pain, stiffness, and physical abilities in knee arthritis patients. Like all such scales, it has what’s called a Minimal Clinically Important Change (MCID) for various treatments. Meaning, if you beat the MCID for WOMAC, then the effect is something that a patient would find clinically meaningful. If you can’t beat the MCID, that’s a problem. That’s why in all of our clinical trials, I have always required our therapies not just to show statistically significant effects, but also to beat the MCID, which defines clinically relevant.

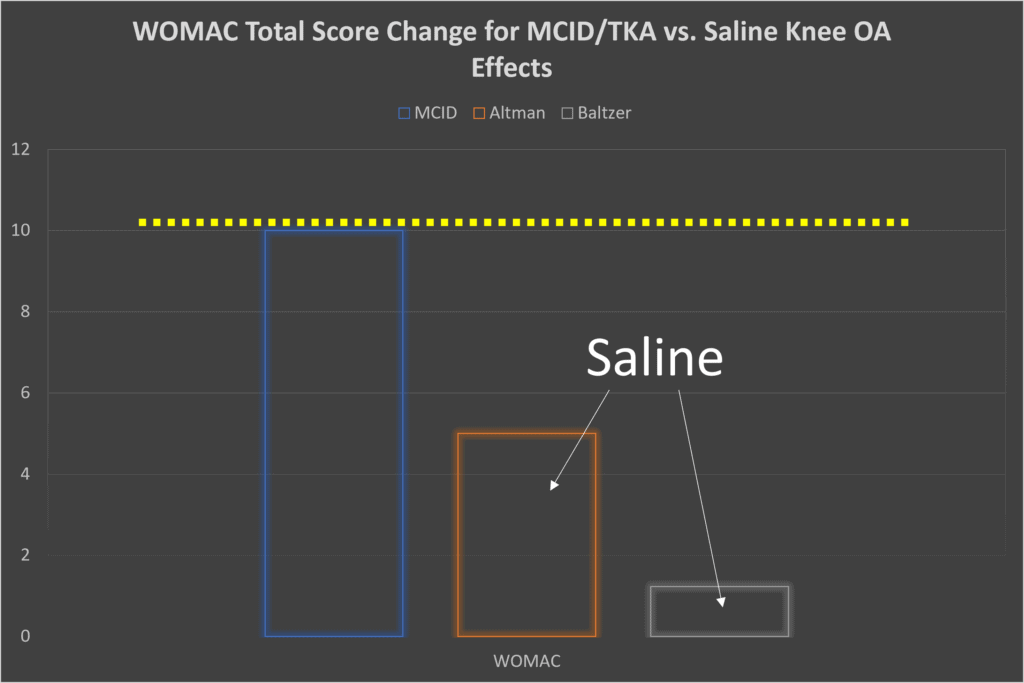

So how did saline do compared to the WOMAC MCID for knee replacement (which is the therapy that all of these knee arthritis treatments compete against)?

[Change in WOMAC total score at 6 months for saline versus MCID.]

In the graph above, the yellow dashed line is the MCID bar that saline would have to best for it to be considered an effect that the average patient would label as a big change in their condition. How did saline do in the two easily downloadable studies? Poorly. It didn’t come close to producing an effect that beat the MCID.

What Does All of This Mean?

At the end of the day, while saline has a treatment effect that is statistically significant, it’s not clinically relevant. Meaning, the idea that treatments that can’t beat saline should be reconsidered because they’re good treatments, isn’t tenable based on what I reviewed. So while researchers may want to petition FDA not to use saline as a placebo treatment and instead to use a standard of care treatment for comparison (like physical therapy or steroid injections) if the drug can’t beat saline, that still means that it’s a drug that most physicians and patients wouldn’t find helpful.

The upshot? I’m glad I took the time to deconstruct this idea that saline is an effective treatment. It’s clearly not. It does have a treatment effect that researchers who design studies need to understand, but at the end of the day, that effect is not clinically important.

____________________________________________

References:

(1) Nees TA, Rosshirt N, Zhang JA, et al. Synovial Cytokines Significantly Correlate with Osteoarthritis-Related Knee Pain and Disability: Inflammatory Mediators of Potential Clinical Relevance. J Clin Med. 2019;8(9):1343. Published 2019 Aug 29. doi:10.3390/jcm8091343

(2) Altman RD, Devji T, Bhandari M, Fierlinger A, Niazi F, Christensen R. Clinical benefit of intra-articular saline as a comparator in clinical trials of knee osteoarthritis treatments: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016 Oct;46(2):151-159. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.04.003. Epub 2016 Apr 27. PMID: 27238876.

(3) Baltzer AW, Moser C, Jansen SA, Krauspe R. Autologous conditioned serum (Orthokine) is an effective treatment for knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009 Feb;17(2):152-60. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.06.014. Epub 2008 Jul 31. PMID: 18674932.

(4) Altman RD, Akermark C, Beaulieu AD, Schnitzer T; Durolane International Study Group. Efficacy and safety of a single intra-articular injection of non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASHA) in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004 Aug;12(8):642-9. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.04.010. PMID: 15262244.

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.