Loose Ligamentum Teres? A New Injection May Help

The ligamentum teres, which lives in your hip, is the red-headed stepchild of ligaments. I say that because most doctors couldn’t tell you where it lives, and the ones who know it’s in the hip mostly ignore it. Yet this ligament is critical for hip stability in dancers, figure skaters, and other athletes who use their hips to extremes. This week we performed another ligamentum teres injection after, I think, performing the world’s first such injection a few months ago. Our goal was to prevent an arthroscopic hip surgery for a dancer with a loose ligamentum teres.

What Is the Ligamentum Teres?

Your hip is a deep ball and socket, where the stability with common things like walking is provided by that deep-set joint. However, if you do more, the hip muscles and ligaments kick in to provide stability. Do even more, like bring your leg above 90 degrees or overhead or get into a “splits” position, and the ligamentum teres is key in preventing the hip from popping out of the socket.

The ligamentum teres is a ligament that lives deep in the hip and attaches the socket to the ball. When you lift your leg, it supports the bottom of the ball in the socket and keeps it from popping out.

Dancers, figure skaters, and yoga enthusiasts rely on this ligament to stabilize the hip when their legs are up in the air or flexed to extremes. When this ligament gets damaged or becomes lax due to partial tears, their hips can feel unstable. In my experience, a common cause of ligamentum teres laxity is arthroscopic hip surgery. Let me explain.

My Ligamentum Teres Nightmare Caused by Hip Surgery

Many years ago, we were using cadavers to test new hip-injection techniques for stem cells. I had borrowed a hip-traction device from a local orthopedic-surgery clinic that specialized in hip arthroscopy. My goal was simply using this traction that was designed to open an area for hip surgery to instead try to get cells to pool in the weight-bearing area of the hip. So I began by applying a small amount of traction at 20 pounds to these experimental hips. The problem, I soon realized, was that I could only do this once as by the second round, the ligamentum teres was so stretched out that the cadaver hip was ruined. The surgical tech working with us reminded us that in the average hip-arthroscopy surgery, much more traction was pulled on the hip to open a working area for the scope (often 60 pounds or more)! Hence, we were observing that the traction used in hip arthroscopy was likely stretching out the ligamentum teres. While most of these ligaments likely healed in the downtime after surgery, what happens to those patients who can’t heal this surgery-created instability? Looks like hip surgeons are just beginning to recognize that this is an issue.

Labral Tears, Impingement, and Ligamentum Teres

Modern orthopedic surgery suffers from what I call the “bright shiny object” syndrome. Meaning that surgeons will focus on an MRI finding after performing a cursory and body-part-limited exam and perform surgery on the “bright shiny object” on MRI, but never ask themselves why the MRI looks that way. In the case of hip labral tears and “impingement,” this is all too common.

Recently a paper was published out of Minnesota by a private-practice orthopedic sports surgeon. The researcher examined the ligamentum teres during more than 2,000 hip-impingement and labral surgeries and found that a startling 88% were frayed or partially torn, 1.5% were completely torn, and only 11% were normal! He noted very smartly that this likely indicates that the labral tears and “impingement” he was surgically treating were likely caused by instability. Meaning that a hip moving around too much in the socket due to a lax ligamentum teres was causing the lip of that socket (the labrum) to get beat up. That, in turn, was causing bone spurs. So I’ll take it one step further, fixing the bone spurs and the labral tears makes little sense if the hip is left unstable due to ligamentum teres tears, as all of this will just return. Add to that our observation that the surgery itself is likely causing hip instability in some patients, and you have an epidemic of loose hips.

Our Novel Ligamentum Teres Injection Technique

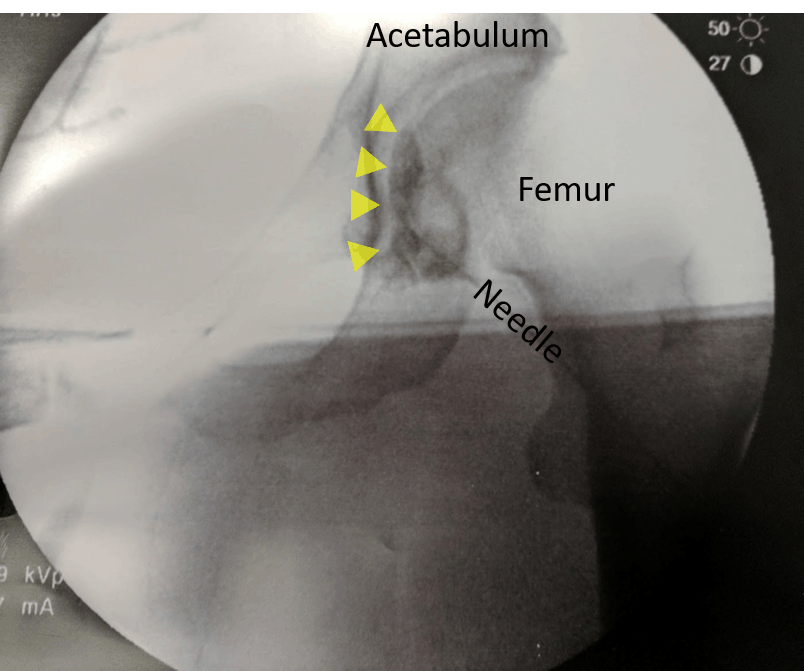

Last year I was approached by a ballet dancer who we had treated before about whether we could inject the ligamentum teres with stem cells. I quickly learned that there is no text or course that covers how one would go about injecting this ligament under imaging guidance. Hence, I would have to map this out and develop a technique to perform this procedure. I performed that injection about two months ago, and this past week Dr. Pitts followed with another injection in a dancer, which is below.

The image to the left shows the needle targeting the bottom of the hip joint. The yellow arrows point to the radiographic contrast that outlines the ligamentum teres. I believe that this image, and the one I have on the ballet dancer I treated, are the only two in existence that demonstrate that this key ligament has been successfully injected.

This Is What Interventional Orthopedics Is All About…

The surgery to fix a loose or partially torn ligamentum teres is a big deal and very invasive. So much so that many dancers who have this diagnosis are told by hip surgeons not to get this operation. How would that decision matrix change if we could inject this ligament with stem cells or PRP and cause it to heal without surgery. This is interventional orthopedics at its best—the precise targeting of specific injured structures with orthobiologics that facilitate healing and, as a result, replace invasive orthopedic surgeries.

The upshot? We’ll see how these two patients ultimately fare. However, I’m proud of our clinic for leading the way again in helping athletes avoid invasive and often career-ending surgeries. We’ll continue to perfect this novel ligamentum teres procedure. In the meantime, it appears that we may be able to help many dancers and other athletes avoid getting their hip ripped apart.

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.