Meniscus Surgery Arthritis: Removing a Small Amount of Meniscus Causes Problems

Is there such a thing as meniscus surgery arthritis? We’ve known since the 1940s that removing the knee meniscus when it was torn was a dumb idea. Since then many studies have shown that patents who get knee meniscus surgery are more likely to get knee arthritis. The knee arthroscopy community has generally responded that removing just a small amount of the meniscus should be fine. Now yet another research study shows why this is ill advised.

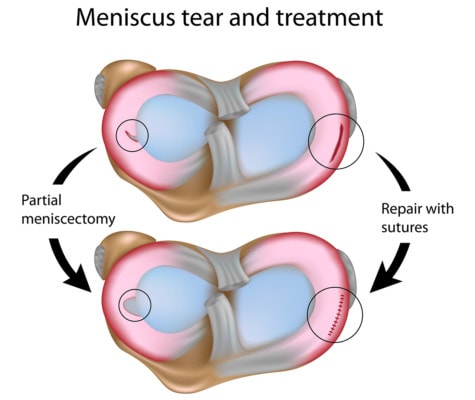

Alila Medical Media/Shutterstock

The meniscus is an important spacer and shock absorber for the knee that protects the cartilage on the ends of the bones. Most patients with a meniscus tear believe that their surgery is to repair the torn meniscus. However, a recent study showed that only 4% of meniscus surgeries involved repair, while 96% involved removing parts of the meniscus. This surgery is called a partial menisectomy. So odds are, if you’re planning a meniscus surgery or have had one, a partial menisectomy was performed.

Way back in the 1940s, a British surgeon noted that when he surgically removed the meniscus, his patients got arthritis at a much more rapid pace. Despite this early observation, surgeries to remove parts of the meniscus became one of the most common surgeries performed in the U.S. with more than 700,000 operations performed annually. You would think with how common the surgery has become that we would have great scientific evidence that the surgery works. Nope. In fact other studies have since shown that taking out parts of the meniscus can increase the forces that lead to arthritis. In fact in one study, 60% of patients got arthritis within just a few years of getting meniscus surgery. A quartet of recent high quality studies have also shown that meniscus surgery just plain doesn’t help patients, regardless of the circumstance.

So why are we still performing an ineffective surgery? I suspect it’s because athletes are still getting these surgeries. While there’s no scientific rationale for athletes to get the surgery either, the calculus with professional athletes is different. Even though we don’t have any data that the surgery will help the athlete, the down time alone will help them heal a bevy of other aches and pains and it’s become acceptable to their professional league to take time off for such a surgery. In other words, it’s athletic tradition to get the surgery without science to support it will help the player. Many patients see their favorite athletes getting these surgeries and figure that it must be the right thing to do when their meniscus tears.

The new study on meniscus surgery and arthritis looked at patients over time as they had their surgery and then followed them for 2 years. They measured a few bio mechanical parameters with walking, but one interesting one was peak force in the leg as it begins to hits the ground. This force was important because earlier studies had associated an increase in this metric with more arthritis. Sure enough, in the partial meniscectomy patients versus the non-operated group, this peak force increased. So the authors concluded that this was a bit of a double whammy for knee surgery patients. Not only is the cushioning effect of the meniscus compromised because there’s less of it, but for some reason the whole leg is taking more force of the type that can lead to arthritis!

The upshot? There are no spare parts in the body that can be removed. Knee meniscus surgery has no evidence that it’s effective and there’s evidence that it harms knees by leading to more arthritis. This last bit of evidence continues to mount. So why are we still doing these surgeries again?

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.