MIS, the Minuteman, and Fusion: Is This a Good Idea?

I cruised around on Linkedin this morning and chanced upon a discussion where someone had fused a patient for a herniated disc. This raised a critical point regarding fusion and the new trend for interventional pain management (IPM) physicians to fuse patients using “MIS.” Let’s review that idea through one specific device that IPM physicians use called “Minuteman.”

What is MIS?

MIS stands for Minimally Invasive Surgery. This has been a trend in spine surgery for some time, focusing on procedures that can be done through smaller incisions. However, lately, these smaller procedures have also been offered by non-surgeons. Most of these physicians are interventional pain management physicians.

What is Minuteman?

Minuteman is a screw that is placed sideways across the spinous processes and locked in place. The goal is to fuse the spinal segment so it can no longer move and to deliver this screw in a procedure that can be performed by a wide array of providers, from spine surgeons to interventional pain physicians.

How common is the use of this device among IPM doctors? I reviewed the LinkedIn posts from the company that makes the device (Spinal Simplicity) to see which provider types are posting on that thread. All of the providers were IPM physicians (the first ten that I counted). Hence IMHO, it’s reasonable to conclude that this device is being marketed as a way for IPM physicians to fuse their patients.

The Linkedin Post that Got Me Thinking This Morning

The post that I found that prompted this blog was about new professional guidelines and had mentioned that a physician used MIS fusion to treat a herniated disc, which is below the current standard of care for those devices. On that thread was an insightful comment from an academic pain physician:

“Unfortunately, too many patients are being treated with whatever reimburses the highest instead of EBM. I remember fellowship training emphasized that fusions were reserved for structural and instability issues, and the goal of pain management was trying to avoid invasive surgical options as much as possible. As soon as pain and other specialists were trained and able to bill for these high paying procedures in their ASCs, somehow “everyone needs a fusion”. These surgeries will unfortunately continue to be abused and I wonder how many of these patients also end up getting a SCS trial afterwards for “failed back” 😉”

This comment encapsulates what I see every day. Some IPM physicians, whose job was to keep people out of surgery through image-guided pain procedures, are now fusing patients themselves. Why? Is the research that good that devices like Minuteman are truly revolutionary? First, let’s review the science behind fusion, and then we’ll delve into this specific device.

The Research Behind Fusion

I’ll break this into a few categories:

- Serious Complications

- Outcomes

- Adjacent Segment Disease

Serious Complications

Spinal fusion complications are common. First, it’s well known that spine surgeons generally have under-reported complications (1). That’s a phenomenon that I’ve observed for years. The patient comes back with more pain or a new problem after the fusion, and the surgeon looks at the films and comments that the fusion looks solid and discharges the patient or refers to an IPM physician.

Taking that underestimate of complications into account, the serious complication rate of spine surgery has been reported to be 10-24% (2). Even minimally invasive fusions of the type we’re discussing here have a reported complication rate of 19%, with some studies reporting that the bigger fusion surgeries that use a full incision have complication rates as high as 31% (3). Specifically, complications can include nerve damage, infection, increased pain, hardware failure, and the need for more surgery.

Outcomes

The single biggest question about fusion is whether taking the additional risk of adding the hardware to fuse the spine creates a better outcome for the patient. Regrettably, the research has shown that this answer is a resounding “No.”

Here’s what we know:

- Back pain, quality of life, and disability have been shown to be no better with a fusion than they are with conservative approaches alone (4).

- Physical therapy was shown to be as effective at relieving pain and restoring function as a back fusion (5).

- Two- and five-year post-surgery outcomes were no better for patients with fusions than for those who only underwent a laminectomy (decompression) (6).

- A Scandanavian paper published in the NEJM randomly assigned patients with Degenerative Spondylolisthesis (slippage of one vertebra on the other) to either fusion or just surgical decompression (7). After two years, there was no benefit to adding a fusion.

- A meta-analysis of eleven studies compared fusion to decompression surgery (7). The results of more than three thousand patients demonstrated that there was no difference in results between fusion and decompression alone (8).

Adjacent Segment Disease

What happens when you fuse a spinal segment? That site sends forces to the adjacent areas, which in many patients, over time, break down and get arthritic. The problem with this phenomenon is that it takes years to show up and depends on patient activity, genetics, and other factors.

How much of an issue is ASD? Two years after a low back Fusion, 12% of patients will have evidence of ASD (9). From there, about 2-4% of patients will develop this problem every year after the fusion. Hence, five years later, up to 20% of patients will have ASD (10).

Minuteman Research

I could find no published research listed in the US National Library of Medicine on the safety or efficacy of the Minuteman device as of this writing.

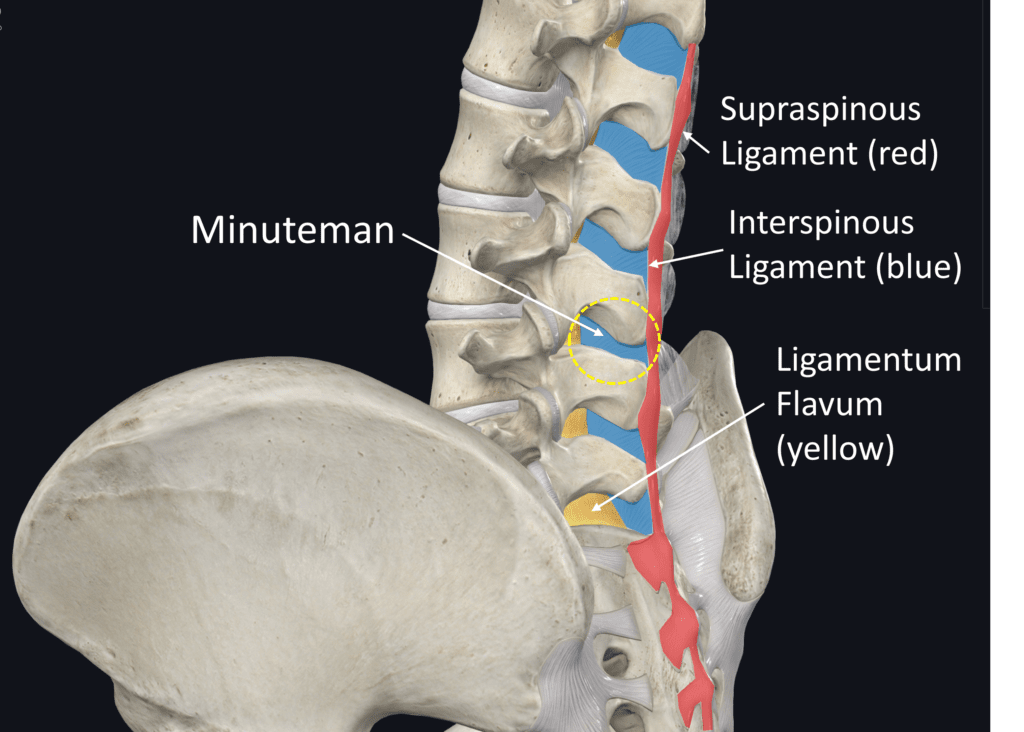

What is Destroyed by Inserting a Minuteman or Similar Device?

On the low back anatomy illustration above, note the interspinous ligament in red. This is one continuous band that anchors in the sacrum and attaches each spinous process in the back to the next vertebra. This continuous strong ligament band is critical in helping to stabilize the entire spine. The Minuteman device disrupts this structure. What happens when you cut this ligament at one level? That likely destabilizes the levels above and below as they no longer have the tension provided by the whole system.

Next up is the interspinous ligament in blue. This critical ligament attaches to the ligamentum flavum (LF), as shown in yellow. The LF requires tension to stay out of the spinal canal when the patient is upright or in extension. Hence, what happens when you destroy the interspinous ligaments? That critical tension is lost, IMHO likely leading to more problems with LF-caused spinal stenosis down the road.

Finally, what happens to the multifidus muscles that actively stabilize this now-fused segment? They are no longer required to work, so they will atrophy.

Summary

Even if the Minuteman device is less invasive (remember MIS fusion, in general, has a reported complication rate of about 19%), it’s reasonable to assume that it still has the problem of causing ASD. In addition, you’re destroying the critical ligament structures that will destabilize other areas of the spine. Finally, you can kiss the active stabilization system (multifidus muscles), as the body has a strict “use it or lose it” rule. In other words, fusing any level, no matter how small a procedure, will cause these critical muscles to go south.

The upshot? Why are IPM physicians who have been charged with helping patients avoid big surgeries like fusion now offering MIS fusions themselves? While I have my theories, I’ll let you be the judge.

_______________________________________________________________

(1) Ratliff JK, Lebude B, Albert T, Anene-Maidoh T, Anderson G, Dagostino P, Maltenfort M, Hilibrand A, Sharan A, Vaccaro AR. Complications in spinal surgery: comparative survey of spine surgeons and patients who underwent spinal surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009 Jun;10(6):578-84. doi: 10.3171/2009.2.SPINE0935.

(2) Zaina F, Tomkins-Lane C, Carragee E, Negrini S. Surgical versus non-surgical treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(1):CD010264. Published 2016 Jan 29. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010264.pub2

(3) Joseph JR, Smith BW, La Marca F, Park P. Comparison of complication rates of minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion and lateral lumbar interbody fusion: a systematic review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus. 2015 Oct;39(4):E4. doi: 10.3171/2015.7.FOCUS15278.

(4) Hedlund R, Johansson C, Hägg O, Fritzell P, Tullberg T; Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. The long-term outcome of lumbar fusion in the Swedish lumbar spine study. Spine J. 2016;16(5):579-587. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2015.08.065

(5) Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, Tosteson A, et al. Long-term outcomes of lumbar spinal stenosis: eight-year results of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT). Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015;40(2):63-76. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000731

(6) Försth P, Ólafsson G, Carlsson T, et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Fusion Surgery for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(15):1413-1423. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1513721

(7) Austevoll IM, Hermansen E, Fagerland MW, Storheim K, Brox JI, Solberg T, Rekeland F, Franssen E, Weber C, Brisby H, Grundnes O, Algaard KRH, Böker T, Banitalebi H, Indrekvam K, Hellum C; NORDSTEN-DS Investigators. Decompression with or without Fusion in Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis. N Engl J Med. 2021 Aug 5;385(6):526-538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2100990. PMID: 34347953.

(8) Dijkerman ML, Overdevest GM, Moojen WA, Vleggeert-Lankamp CLA. Decompression with or without concomitant fusion in lumbar stenosis due to degenerative spondylolisthesis: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2018 Jul;27(7):1629-1643. doi: 10.1007/s00586-017-5436-5. Epub 2018 Feb 5. PMID: 29404693.

(9) Zhong ZM1 Deviren V, Tay B, Burch S, Berven SH. Adjacent segment disease after instrumented fusion for adult lumbar spondylolisthesis: Incidence and risk factors. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2017 May;156:29-34. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2017.02.020.

(10) Tobert DG, Antoci V, Patel SP, Saadat E, Bono CM. Adjacent Segment Disease in the Cervical and Lumbar Spine. Clin Spine Surg. 2017 Apr;30(3):94-101. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000442.

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.