Everything You Need To Know About Posterolateral Corner Injuries

Medically Reviewed By:

The knee’s posterolateral corner (PLC) plays a critical role in stabilizing the knee joint, especially by preventing outward rotation and backward sliding of the tibia. PLC injuries are common among athletes, accounting for approximately 7-16% of all knee ligament injuries.

These injuries can significantly impact daily activities, leading to knee instability, difficulty walking, and pain when navigating uneven surfaces. While surgery may be considered for some PLC injuries, many cases do not require it. Accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment are necessary to support recovery and prevent long-term instability.

Let’s explore the specifics of PLC injuries, including cases where conservative treatments or less invasive regenerative therapeutics may be sufficient.

Anatomy Of The Posterolateral Corner

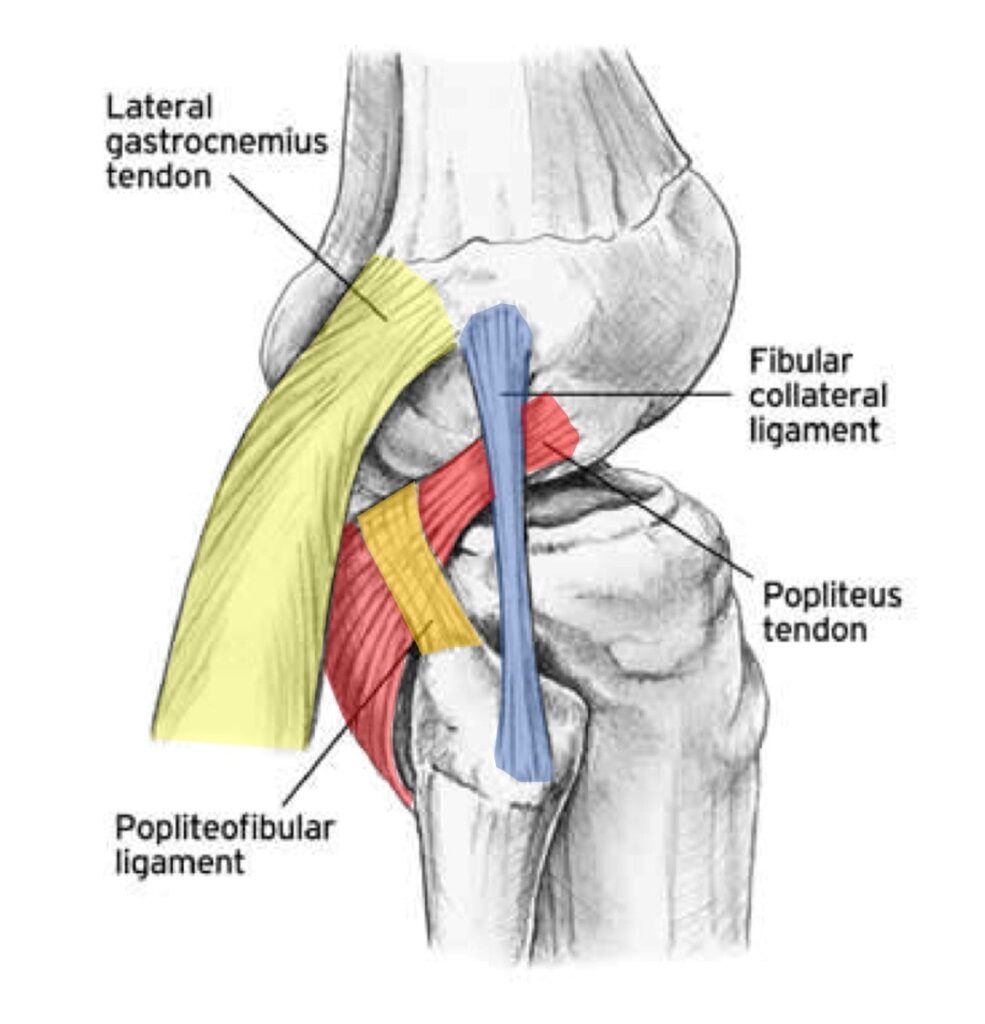

The PLC of the knee is a complex anatomical area critical for maintaining knee stability, particularly during rotational movements and resisting external forces. Several key structures, including ligaments, tendons, and muscles, work together to stabilize this region.

- Posterolateral meniscus: This part of the meniscus complex acts as a shock absorber for the knee. Injuries to the posterolateral meniscus can occur in the PLC, but degenerative tears, especially in individuals over 35, are common and may not be the source of pain. Research indicates that conservative treatments, such as physical therapy, can provide effective outcomes comparable to surgeries like partial meniscectomy.

- Popliteus tendon: This tendon sits in a bony groove at the back of the knee and helps move the meniscus during knee flexion. Injuries to the popliteus tendon can contribute to PLC pain and cause what’s known as the “boot sign,” where patients experience pain when removing footwear by using the opposite foot.

- Popliteofibular ligament: This ligament wraps around the popliteus tendon and controls tibial rotation like the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). It is essential for preventing excessive tibial rotation.

- Biceps femoris tendon: This tendon attaches the biceps femoris muscle to the fibula. Injuries to this tendon may be caused by irritation or nerve dysfunction, often resulting in pain that worsens with knee flexion.

- Lateral collateral ligament (LCL): Positioned on the outside of the knee, the LCL prevents excessive inward or varus pressure. While injuries to this ligament are often described as tears on MRI, many are partial injuries that do not require surgery, as the ligament may still be functional.

- Fibular head: The fibula connects to the tibia at the fibular head, held on with strong ligaments (tibiofibular). This joint can become arthritic or damaged, and instability in the joint may irritate surrounding structures.

- Peroneal nerve: The peroneal nerve wraps around the fibular head and can become irritated if the fibula is unstable, leading to tingling, numbness, or burning sensations along the leg and foot.

- Lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle: This part of the calf muscle attaches to the femur and can be injured, leading to pain during activities like stepping on the gas pedal (dorsiflexion).

Role Of The PLC In Knee Stability

The PLC plays a vital role in maintaining knee stability by preventing excessive twisting and hyperextension. Under typical conditions, ligaments, tendons, and muscles stabilize the joint, allowing for controlled movement. However, instability occurs when these structures are damaged, leading to abnormal motion that can further compromise knee function.

The PLC specifically resists excessive external rotation and backward sliding (posterior translation) of the tibia. This function is especially important during activities like walking, running, and pivoting, which put lateral and rotational forces on the knee.

The lateral collateral ligament (LCL), popliteus tendon, and popliteofibular ligament are particularly important in controlling these movements, helping to guide the joint through its range of motion and protect it from injury.

When internal knee ligaments like the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) or posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) are compromised, the PLC experiences increased stress. This additional stress can lead to further damage and exacerbate knee instability, resulting in buckling, increased fall risk, and difficulty controlling movements essential for daily activities and athletic performance.

Leading Causes Of Posterolateral Corner Damage

Several factors can lead to PLC injuries, many of which involve high-energy trauma or excessive forces acting on the knee joint. Here are the most common causes:

Trauma And High-Energy Injuries

High-energy impacts, such as those from sports like football or skiing, can place extreme force on the knee, leading to PLC damage. Car accidents and falls also pose a high risk, often causing dislocation or overstretching of the ligaments and tendons in the PLC, resulting in knee instability.

- Sports injuries: Contact sports like football, where sudden tackles or collisions occur, and high-impact activities like skiing, which involve quick directional changes, can significantly damage the PLC by putting excessive forces on the knee.

- Car accidents: The impact from car accidents often leads to knee dislocation or other traumatic injuries that can damage the structures of the PLC.

- Falls: A severe fall, particularly on a flexed or twisted knee, can result in PLC injury by overstretching or tearing the ligaments and tendons that provide stability.

Combined Knee Injuries

PLC damage often occurs alongside other knee injuries, especially with tears in the ACL or PCL. These combined injuries stress the PLC more, weakening the joint’s overall stability. In cases where both the PLC and cruciate ligaments are injured, patients often experience more severe knee instability and a higher risk of long-term joint dysfunction.

This combination of injuries may also complicate recovery and necessitate a more comprehensive treatment and rehabilitation approach.

Hyperextension Of The Knee

When the knee is forced into hyperextension, it can overstretch the ligaments and tendons in the PLC, leading to instability or tears. This is common in activities where the knee locks or extends beyond its normal range.

Hyperextension injuries are particularly problematic because they damage the PLC and can strain other critical knee structures, intensifying the injury. Untreated hyperextension injuries can lead to chronic instability and an increased likelihood of future knee issues.

Rotational Injuries

Sudden twisting motions, often seen in sports or accidents, can overstress the PLC by rotating the tibia externally beyond its normal range, leading to ligament or tendon damage. These rotational forces often occur when the foot is planted while the rest of the body turns, putting the knee at high risk.

Over time, repeated rotational injuries can result in permanent ligament damage and increased vulnerability to future knee injuries. Early intervention is crucial to preventing long-term instability.

Recognizing Symptoms Of PLC Injuries

PLC injuries can manifest through various symptoms, often impacting the knee’s stability and function. Identifying these symptoms early is crucial for proper diagnosis and treatment.

- Knee Instability: Patients often report the knee “giving out” during movement, particularly when walking on uneven surfaces or suddenly changing directions.

- Swelling and Bruising: Swelling and bruising manifest due to trauma sustained by the ligaments and surrounding tissues, which may increase after physical activity or weight-bearing.

- Lateral Gapping: This is an abnormal widening of the joint on the outer side, suggesting the stabilizing ligaments are no longer functioning properly, increasing instability with pressure.

- Back-Of-Knee Pain: Pain behind the knee may result from conditions such as tendonitis, a Baker’s cyst, or hamstring strain. It may cause stiffness, swelling, or discomfort, often worsening with movement or prolonged activity. Read More About Back-Of-Knee Pain.

- Side-Of-Knee Pain: Pain on the side of the knee may result from ligament injuries, iliotibial (IT) band syndrome, or meniscus issues. Accompanying symptoms can include tenderness, swelling, and discomfort, often worsening with movement or prolonged activity. Read More About Side-Of-Knee Pain.

Methods For Accurate Diagnosis Of Posterolateral Corner Injuries

Diagnosing PLC injuries accurately requires a combination of physical examinations, specialized tests, and imaging techniques to assess the severity and extent of the damage.

Physical Examination

A thorough physical examination is the first step in diagnosing PLC injuries. The clinician evaluates the knee for instability, swelling, and tenderness in the lateral area. This exam helps determine which ligaments and structures may be compromised.

Specialized Tests

Specialized tests help assess knee stability and identify which structures in the PLC are damaged. These tests, such as the varus stress and dial tests, apply pressure to evaluate ligament integrity and pinpoint instability.

- Varus stress test: This test applies outward pressure on the knee to assess the integrity of the lateral collateral ligament (LCL).

- Dial test: The dial test checks for excessive external rotation of the tibia, which can indicate PLC injury.

- Gait exam: The patient’s walking pattern is analyzed to detect any instability or abnormal motion that might suggest PLC involvement.

- External rotation recurvatum test: This test evaluates knee hyperextension and external rotation to identify excessive movement commonly associated with PLC damage.

- Posterolateral drawer test: By applying force to the tibia, this test assesses the posterior movement of the tibia within the knee joint, a key indicator of PLC injury.

- Reverse pivot shift test: This test detects abnormal knee shifting during flexion, a common symptom in PLC injuries.

Imaging Techniques

Imaging techniques such as MRI and stress radiographs provide detailed views of the soft tissues and measure joint stability under stress. These methods confirm the extent of ligament and tendon damage in PLC injuries.

- MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging provides detailed images of soft tissues, allowing for the identification of ligament, tendon, and muscle injuries in the PLC.

- Stress radiograph: This imaging technique measures joint gapping under stress to evaluate the extent of ligament damage and instability in the knee.

- Ultrasound: Ultrasound uses sound waves to provide real-time images of soft tissues, helping assess ligament damage and joint stability in PLC injuries. It’s a quick, cost-effective alternative to MRI.

Does A Posterolateral Corner Injury Heal?

Many PLC injuries can heal with time and rehabilitation, especially when treated early. The initial approach typically involves bracing the knee for four to six weeks to limit movement and promote healing.

Physical therapy (PT) focuses on strengthening the muscles that support knee stability, including those at the spine, hip, hamstrings, and popliteus.

Exercises to enhance knee stability during activities like landing and movement are often introduced as the knee improves. However, more severe injuries may require surgical intervention if the ligaments are significantly damaged or if the knee remains unstable after conservative treatment.

Conventional Treatment Options For PLC Injuries

Treating PLC injuries depends on the severity of the damage. Conservative treatments are usually the first approach, but more severe or unresponsive cases may require surgical intervention.

- Knee bracing: Often the first line of treatment, this is typically worn to limit knee movement and allow healing by stabilizing the ligaments and tendons.

- Physical therapy: PT typically accompanies bracing, and focuses on strengthening surrounding muscles to improve joint stability. Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) Injections

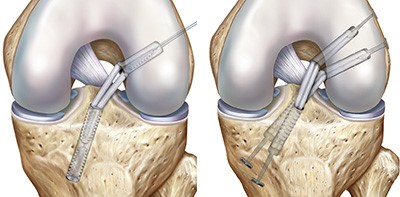

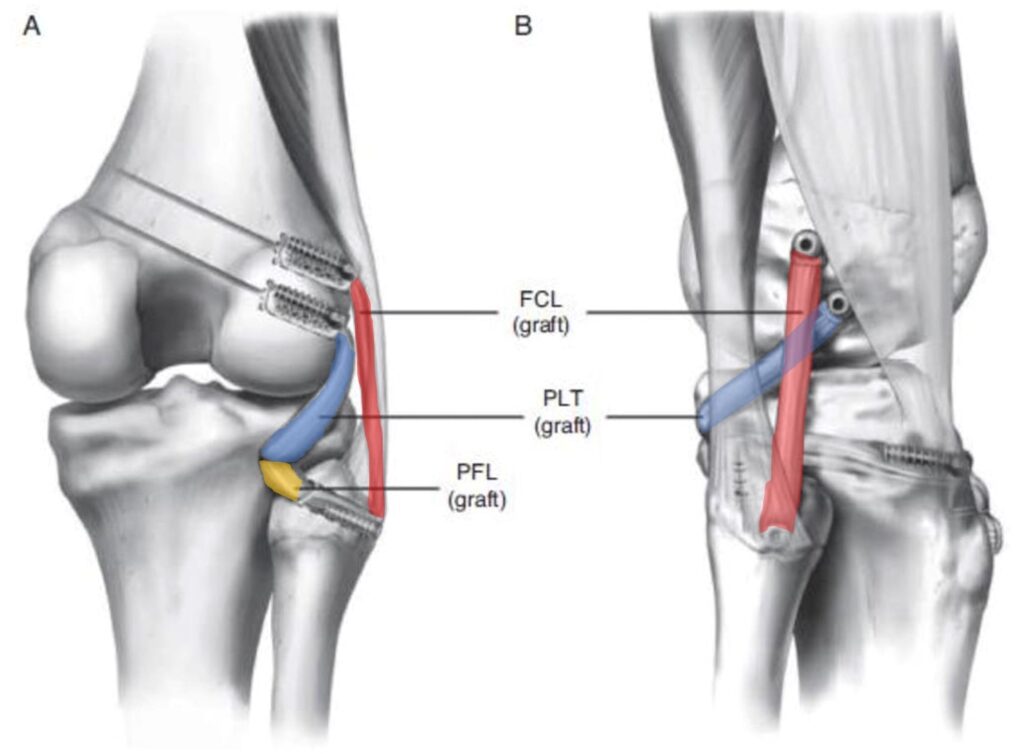

Reconstruction surgery for severe injuries with chronic instability often involves using tendon grafts to repair torn ligaments like the LCL or PCL. For PCL injuries in the posterolateral corner (PLC), multiple structures, such as the popliteus tendon and proximal tibiofibular joint, may be targeted. Surgeons choose between single-tendon or two-tendon reconstruction based on injury severity.

The two-tendon approach, specific to PCL reconstruction, offers more robust stabilization but comes with increased technical complexity. In some cases, these surgeries can be performed together to address multiple areas of damage, enhancing overall knee stability and recovery.

For instance, in lateral collateral ligament reconstruction, a tendon graft (shown in red) is anchored into the femur (thigh bone) and threaded through a tunnel drilled in the fibula. The popliteus tendon and ligament are reconstructed using a tendon (blue) anchored in the front of the tibia, which is then passed to the back and up to the femur.

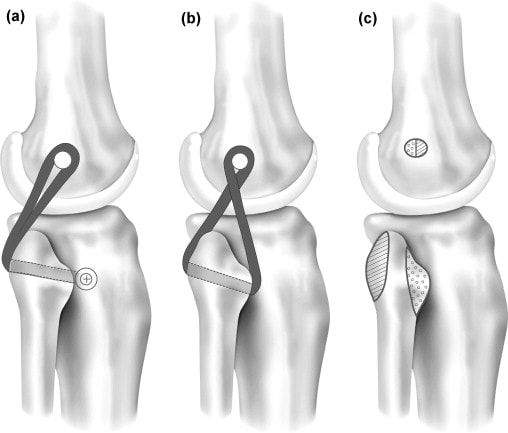

Another tendon (yellow) is also threaded through the same tibial tunnel and anchored into the fibula to recreate the ligament connecting the tibia and fibula. For tibiofibular joint reconstruction, when the ligaments that hold the fibula to the tibia are damaged, a tendon is anchored to the femur, passed through a drilled hole in the fibula, and threaded back to the femur (below).

In posterior-lateral corner capsular reconstruction, an osteotomy (bone cutting) is performed on the lateral femoral condyle (outer end of the thigh bone) to improve access to the affected area. The joint capsule covers the knee joint and is then sutured to tighten and stabilize the knee, reducing instability.

Surgical Outcomes And Side Effects Of PLC Reconstruction

Surgical outcomes for PLC reconstruction can vary depending on the complexity of the injury. Patients undergoing reconstruction for multiple ligaments, such as combined ACL and PLC injuries, often experience less favorable outcomes compared to those needing a single ligament repair.

For instance, studies have shown that ACL surgeries combined with PLC reconstruction may result in persistent knee instability and decreased function compared to ACL surgery alone. In another study, only about one-third of patients who had both PCL and PLC reconstruction achieved normal ligament function after surgery, while many continued to experience some degree of joint laxity or no improvement.

There are also no studies showing that these procedures are more effective than sham or placebo procedures.

Side Effects Of PLC Reconstruction

Potential side effects of PLC reconstruction include persistent knee laxity, nerve or blood vessel damage, and complications such as bone death (osteonecrosis) or compartment syndrome. Additionally, patients may experience scarring in the knee, reduced range of motion, or pain in the front of the knee.

Other risks include fractures, infection, and wound healing issues, which can further complicate recovery. These risks highlight the importance of carefully considering the benefits and potential complications before surgery.

The Regenexx Approach To A Posterolateral Corner Injury

Physicians within the licensed Regenexx network offer a non-surgical approach to treating PLC injuries with advanced interventional orthobiologics. Procedures using Regenexx proprietary methods promote the body’s natural ability to heal stretched or damaged ligaments, providing a less invasive alternative to procedures like PLC reconstruction surgery.

Orthobiologics are customized and concentrated to address each patient’s unique condition and injected into the area using imaging guidance for precision.

Informed Decisions Will Help To Promote Recovery

Making informed decisions about your treatment is key to promoting the best possible recovery from a PLC injury. Understanding surgical and non-surgical options, such as those offered with the Regenexx approach, can help you choose the path that reduces risks while supporting recovery.

Learn how a physician specializing in using Regenexx injectates can help you explore non-surgical steps toward using your body’s natural healing abilities and improving knee stability.

Get started to see if you are a Regenexx candidate

To talk one-on-one with one of our team members about how the Regenexx approach may be able to help your orthopedic pain or injury, please complete the form below and we will be in touch with you within the next business day.

References

(1) Chahla J, Moatshe G, Dean CS, LaPrade RF. Posterolateral Corner of the Knee: Current Concepts. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2016;4(2):97–103. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4852053/

(2) Risberg MA. Degenerative meniscus tears should be looked upon as wrinkles with age—and should be treated accordingly. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2014;48:741. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2014-093568

(3) Katz JN, Brophy RH, Chaisson CE, et al. Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 15;369(7):683]. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1675–1684. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1301408

(4) Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itälä A, Joukainen A, Nurmi H, Kalske J, Järvinen TL; Finnish Degenerative Meniscal Lesion Study (FIDELITY) Group. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med. 2013 Dec 26;369(26):2515-24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305189.

(5) Jacobson KE, Longacre MD. Posterolateral reconstruction of the knee using capsular procedures for evaluation and treatment of posterolateral instability of the knee. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2015 Mar;23(1):27-32. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000048.

(6) Fanelli GC, Fanelli DG. Fibular head-based posterolateral reconstruction of the knee combined with capsular shift procedure. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2015 Mar;23(1):33-43. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000042.

(7) Fanelli GC, Monohan TJ. Complications in posterior cruciate ligament and posterolateral corner surgery. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine. Volume 9, Issue 2, April 2001, Pages 96-99. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1060187201800174

(8) Cartwright-Terry M, Yates J, Tan CK, Pengas IP, Banks JV, McNicholas MJ. Medium-term (5-year) comparison of the functional outcomes of combined anterior cruciate ligament and posterolateral corner reconstruction compared with isolated anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2014 Jul;30(7):811-7. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.02.039.

(9) Khanduja V, Somayaji HS, Harnett P, Utukuri M, Dowd GS. Combined reconstruction of chronic posterior cruciate ligament and posterolateral corner deficiency. A two- to nine-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006 Sep;88(9):1169-72. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16943466

(10) Petrillo S, Volpi P, Papalia R, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Management of combined injuries of the posterior cruciate ligament and posterolateral corner of the knee: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2017 Sep 1;123(1):47-57. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldx014.

(11) (4) Sihvonen R, Englund M, Turkiewicz A, Järvinen TL; Finnish Degenerative Meniscal Lesion Study Group. Mechanical Symptoms and Arthroscopic Partial Meniscectomy in Patients With Degenerative Meniscus Tear: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016 Apr 5;164(7):449-55. doi: 10.7326/M15-0899.

(12) Katz JN, Shrestha S, Losina E, Jones MH, Marx RG, Mandl LA, Levy BA, MacFarlane LA, Spindler KP, Silva GS; MeTeOR Investigators, Collins JE. Five-year outcome of operative and non-operative management of meniscal tear in persons greater than 45 years old. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1002/art.41082.

(13) Jadhav SP, More SR, Riascos RF, Lemos DF, Swischuk LE. Comprehensive review of the anatomy, function, and imaging of the popliteus and associated pathologic conditions. Radiographics. 2014 Mar-Apr;34(2):496-513. doi: 10.1148/rg.342125082.

(14) La Rocca Vieira R, Rosenberg ZS, and Kiprovski K. MRI of the Distal Biceps Femoris Muscle: Normal Anatomy, Variants, and Association with Common Peroneal Entrapment Neuropathy. American Journal of Roentgenology 2007 189:3, 549-555. https://www.ajronline.org/doi/10.2214/AJR.07.2308

(15) Grawe B, Schroeder AJ, Kakazu R, Messer MS. Lateral Collateral Ligament Injury About the Knee: Anatomy, Evaluation, and Management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2018 Mar 15;26(6):e120-e127. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00028.

(16) Sarma A, Borgohain B, Saikia B. Proximal tibiofibular joint: Rendezvous with a forgotten articulation. Indian J Orthop. 2015;49(5):489–495. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.164041

(17) Van den Bergh FR, Vanhoenacker FM, De Smet E, Huysse W, Verstraete KL. Peroneal nerve: Normal anatomy and pathologic findings on routine MRI of the knee. Insights Imaging. 2013;4(3):287–299. doi: 10.1007/s13244-013-0255-7

(18) Bordoni B, Waheed A, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Gastrocnemius Muscle. [Updated 2019 May 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532946/

(19) Pache S, Aman ZS, Kennedy M, et al. Posterior Cruciate Ligament: Current Concepts Review. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2018;6(1):8–18. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5799606/

(20) Franciozi CE, Albertoni LJB, Gracitelli GC, et al. Anatomic Posterolateral Corner Reconstruction With Autografts. Arthrosc Tech. 2018;7(2):e89–e95. Published 2018 Jan 8. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2017.08.053

Medically Reviewed By: