Regenerative vs. Ablative: The Battle Over Lumbar RFA and Multifidus Atrophy

Medicine advances because advocates for various treatments duke it out in the research literature. That time-honored system produces an intellectual Darwinism effect and one of those evolutionary battles happening in pain medicine is between opposing regenerative and ablative camps. Today we’ll dive into one example of that conceptual crucible by focusing on little muscles in your back that stabilize your spine.

Regenerative vs. Ablative

Regenerative medicine is a philosophy that physicians should be using substances that help the body heal or at least mitigate damage. This whole way of viewing the spine and designing treatments is so dramatically different than traditional pain management that when we add new providers to our national network who are expert pain management physicians, substantial retaining is often required. For example, if you’re treating someone with back pain as a traditional interventional spine physician, you’re taught to identify the most painful structure and inject steroids or kill the nerve carrying those pain signals. However, the regenerative medicine approach is to treat the whole functional spinal unit by stabilizing sloppy movement and treating damaged areas with platelet growth factors.

Ablative care is a mainstay of traditional interventional pain management for the spine. For example, when a nerve is carrying pain signals because a part of the spine is damaged, the doctor ablates that nerve using radiofrequency (RFA or Radiofrequency Ablation). That means that a probe is inserted near the nerve and the radiowaves heat the tissue so that it’s literally cooked and the nerve is killed off. In fact, thermal radiofrequency vendors used to show us chicken breasts with a cooked line in them to demonstrate the efficacy of their RFA probes.

Our practice dropped the use of RFA more than a decade ago and almost two decades ago dedicated itself to developing regenerative techniques for patients with spinal disorders. However, many practices offering regenerative spine care live in both camps. Some have yet to do much regenerative care, instead still focusing on treatments like RFA.

RFA is big business, so despite its destructive nature, the companies that make these machines and expensive disposable probes aren’t going to go quietly into that good night. For example, I blogged many years ago about breaking the wire that went into an RF probe and spending $1,000 to replace a $1 part. So I wouldn’t expect RFA to be fully replaced anytime soon, as the profit margins are just too high.

Multifidus

Credit: Shutterstock

There are little muscles deep in your spine that stabilize one level on another called multifidus. Your spine protects its parts and pieces including the facet joints discs, nerves, and other structures by using these muscles to keep everything aligned with submillimeter precision as you move. For example, if you reach for something, the multifidus muscles in your spine actually precontract by 100 milliseconds so nothing in your spine gets out of place.

We’ve known for decades that when the multifidus muscles in the low back atrophy, back and leg pain follow (1-3). This makes sense because when this muscle isn’t working, critical structures are getting more wear and tear as the person moves, lifts, or twists. Despite this, most radiologists haven’t gotten the memo, so the vast majority of patients with this problem have no idea that they have atrophy causing their back dysfunction. In fact, I’ve seen countless patients with disabling back or leg symptoms who have been told they have a completely normal MRI and who have severe multifidus atrophy on that same MRI. To learn more about the multifidus, see my video below:

RFA and Multifidus

RFA for low back pain usually focuses on ablating the nerve that takes the pain from a damaged and arthritic facet joint. That nerve, the “medial branch” also supplies the multifidus muscle. Hence, from the very first use of RFA for back pain, one way to tell if the RFA was successful was to stick an EMG needle in the multifidus to see if it still had electrical activity. If the muscle was electrically dead, then the RFA was successful. Obviously, killing critical stabilizing muscles in patients with chronic low back pain is not an elegant or smart treatment, as while you’re reducing the facet joint pain felt by the patient, you’re creating a new problem by increasing instability.

In addition, research on multifidus problems after RFA has been published. For example, Dreyfus et al published a small 2009 case series that showed diffuse multifidus atrophy in patients after RFA, but the radiologists reading the low back MRIs couldn’t discern which exact levels had been treated (there’s a reason for that which I’ll discuss below) (4). Wu et al also observed this widespread multifidus atrophy following RFA (5). Wu discussed the reason behind the more diffuse atrophy was that many multifidus levels were actually innervated by the same medial branch.

Polysegmental and Crossed Innervation

As resident physicians in training, we were taught that one spinal nerve (and medial branch) innervated each multifidus muscle, which is why Dreyfus was confused when his study showed that widespread atrophy of the multifidus occurred after RFA. However, like many things in medicine, that “fact” turns out to be fiction when more research is performed. To that end, in 2008, Kottlors et al published showing that (6):

” In conclusion, the medial paraspinal muscles might be thought to be innervated by one single nerve root on anatomical studies, electrophysiologically the extension of axonal lesion signs of one single lumbar nerve root is much broader.”

Translation? When you ablate one medial branch in an RFA, it impacts many multifidus levels. In addition, it also impacts the other side because these nerves cross over from the left to right and vice versa. Keep this in mind as we review some new research highlighted below.

The New Research as Ammunition in the Intellectual Battle

Suffice it to say that if RFA nukes the multifidus muscle, that’s a problem. So we see these intermittent studies which always seem to be published by physicians who are still performing RFA. This new study is no different:

The new research looks super fancy involving “3-D computer-assisted MRI analysis using iSix software”! I’m not sure why you would need software to see multifidus atrophy as it can literally be spotted from across the room on a lumbar MRI, but let’s see what’s up.

First, the study is retrospective, meaning they looked backward at RFA patients that they had already treated. Hence, at no time did they measure the status of the multifidus on MRI, perform an RFA, and then repeat the MRI. They also excluded a huge number of treated patients, starting with 62 patients and excluding 42 for various reasons and ending up with a final n of 20.

The study concludes that RFA doesn’t cause multifidus atrophy. However, right away, in the abstract, there’s something fishy:

“A total of 31 treated and 9 non-treated sides (Level L2/3 – L5/S1) were examined.”

Remember, if we’re trying to compare one treated level or side to a level or side that was untreated that’s a problem. Why? Because one treated medial branch nerve supplies many levels as well as the opposite side. So what you think went untreated that could be used for comparison is actually going to show multifidus atrophy as well.

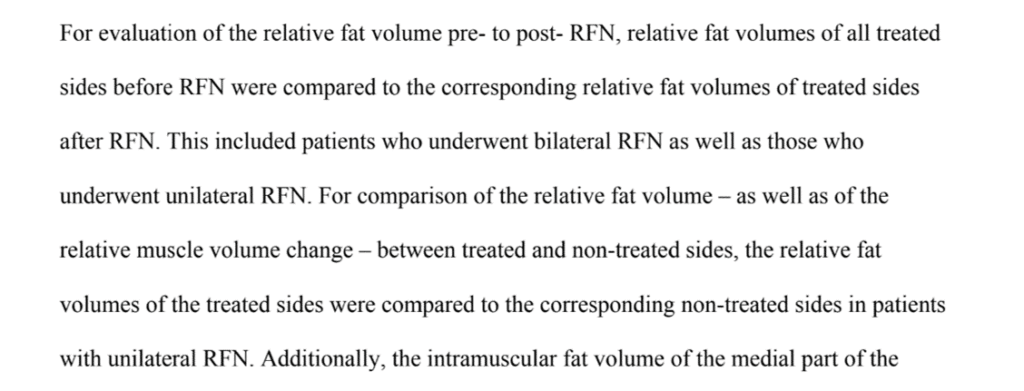

This problem is also confirmed by this statement in the paper:

Basically, as suspected, the authors assumed they could compare the treated side to the nontreated side. So if you’re relying on that side-to-side comparison to show that the treated left looks the same as the untreated right, that’s not going to work as the multifidus atrophy you caused on the left through an RFA would impact the right.

The authors also reported confusingly that they somehow compared what sounds like the same side before and after, but it was never really spelled out how this was done. For example, nowhere in the paper does it state for example that R L5-S1 was treated in X number of patients and that this level was compared before and after. We just get vague statements that relate that treated “sides” were compared to treated “sides”. Which levels on those sides were treated and compared? Your guess is as good as mine.

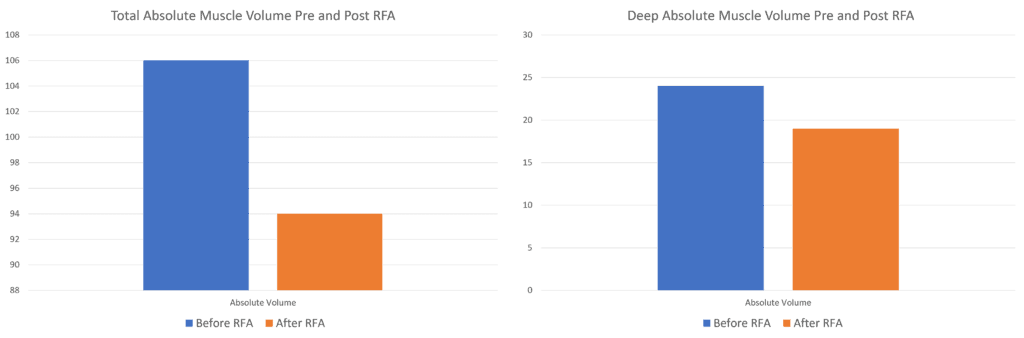

Hiding Decreased Muscle Volume Post RFA in the Stats

When looking at the discussion of the data in table 3 of the study, the authors make the claim that they observed no decreased muscle size due to RFA. However, that’s not entirely accurate. Above I graphed the author’s data concerning the absolute muscle volume observed in all of the paraspinal muscles versus the “Deep” (read multifidus) compartment pre and post-RFA. There was actually a precipitous drop in muscle volume after RFA. In fact, the only metric where is no drop is in the “relative” volume.

How was relative muscle volume calculated? I could find no explanation either in this paper or the prior paper the authors published on the computerized technique (7). Hence, the conclusions that RFA causes no observed atrophy can’t be supported by this published data.

Thoughts on the Regenerative vs Ablative

This new paper doesn’t really support that RFA has no impact on the multifidus muscle. However, even if somebody can prove that RFA doesn’t cause atrophy of the multifidus (which hasn’t happened to date), we still know that the muscle is electrically silent and not working for some significant time after RFA, leaving that segment unstable for that time period. Meaning there is some time period after RFA where additional damage is happening to the treated segment because the stabilizing muscle is offline.

How could this issue be settled in the research literature? It would take a prospective randomized controlled trial where some patients receive RFA and others do not. These patients would need to be followed with pre and post MRI images and several years of follow-up. The goal would be to look for any additional atrophy in the RFA treated patients as well as more degenerative disease in treated versus untreated patients.

The upshot? At the end of the day, medicine advances when different treatment approaches are used and one wins in the end. That process improves patient care and outcomes. So while the hand wringing over multifidus atrophy may seem like a small thing, it’s really that bigger process of scientific evolution playing itself out. Is RFA the best treatment for a painful low back? Not in our clinic where we jettisoned the practice more than a decade ago. However, I expect we’ll see more back and forth on this topic before it’s settled.

_______________________________________________________

References:

(1) Seyedhoseinpoor T, Taghipour M, Dadgoo M, Sanjari MA, Takamjani IE, Kazemnejad A, Khoshamooz Y, Hides J. Alteration of lumbar muscle morphology and composition in relation to low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine J. 2022 Apr;22(4):660-676. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2021.10.018. Epub 2021 Oct 27. PMID: 34718177.

(2) Kader DF, Wardlaw D, Smith FW. Correlation between the MRI changes in the lumbar multifidus muscles and leg pain. Clin Radiol. 2000 Feb;55(2):145-9. doi: 10.1053/crad.1999.0340. PMID: 10657162.

(3) Goubert D, De Pauw R, Meeus M, Willems T, Cagnie B, Schouppe S, Van Oosterwijck J, Dhondt E, Danneels L. Lumbar muscle structure and function in chronic versus recurrent low back pain: a cross-sectional study. Spine J. 2017 Sep;17(9):1285-1296. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2017.04.025. Epub 2017 Apr 26. PMID: 28456669.

(4) Dreyfuss P, Stout A, Aprill C, Pollei S, Johnson B, Bogduk N. The significance of multifidus atrophy after successful radiofrequency neurotomy for low back pain. PM R. 2009 Aug;1(8):719-22. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.05.014. PMID: 19695523.

(5) Wu PB, Date ES, Kingery WS. The lumbar multifidus muscle in polysegmentally innervated. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 2000 Dec;40(8):483-5. PMID: 11155540.

(6) Kottlors M, Glocker FX. Polysegmental innervation of the medial paraspinal lumbar muscles. Eur Spine J. 2008 Feb;17(2):300-6. doi: 10.1007/s00586-007-0529-1. Epub 2007 Oct 31. PMID: 17972114; PMCID: PMC2365552.

(7) Hoppe, S., Maurer, D., Valenzuela, W. et al. 3D analysis of fatty infiltration of the paravertebral lumbar muscles using T2 images—a new approach. Eur Spine J 30, 2570–2576 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-021-06810-7

If you have questions or comments about this blog post, please email us at [email protected]

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.