Sternocleidomastoid Syndrome: What You Need to Know

What’s on this Page:

- What is sternocleidomastoid syndrome?

- What is the SCM muscle, and what does it do?

- How does sternocleidomastoid syndrome relate to nerves in the neck?

- SCM trigger points and referred pain

- The SCM and vertigo

- Does CCI play a role in sternocleidomastoid syndrome?

If you or a loved one has neck pain, learning about what’s in your neck is important so you can relay what’s wrong to your doctor. So today we’ll cover the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle. When this muscle has a chronic problem, that’s often called sternocleidomastoid syndrome. Let’s dig in.

Sternocleidomastoid Syndrome

This is the term used to describe chronic neck stiffness with decreased neck rotation and pain in the eye, temple, ear, and front of the neck. This is also usually associated with vertigo (dizziness with or without nausea), tinnitus (ear ringing), and chronic neck spasm in one direction (torticollis). To understand what’s going on here, we need to learn about the SCM muscle itself.

Where is the SCM? What Does it Do?

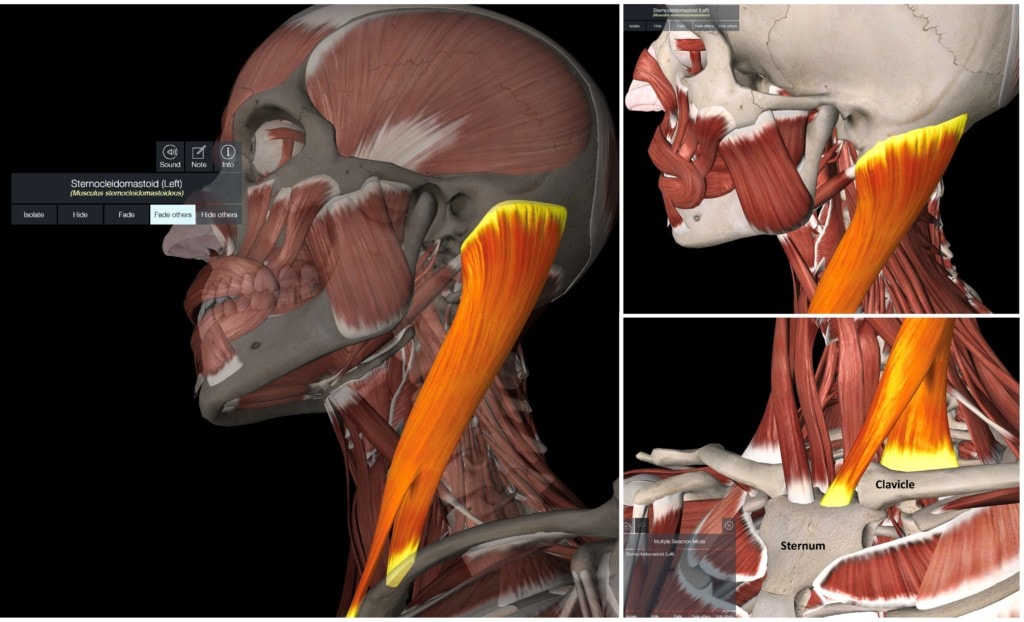

To understand sternocleidomastoid syndrome we first need to learn a little anatomy. The SCM lives in the front of the neck and travels between the skull and the sternum/clavicle (in yellow). It originates from the mastoid process of the skull and travels downward (right upper diagram). It has two heads, one that inserts on the sternum and the other on the clavicle (collar bone) (right lower diagram).

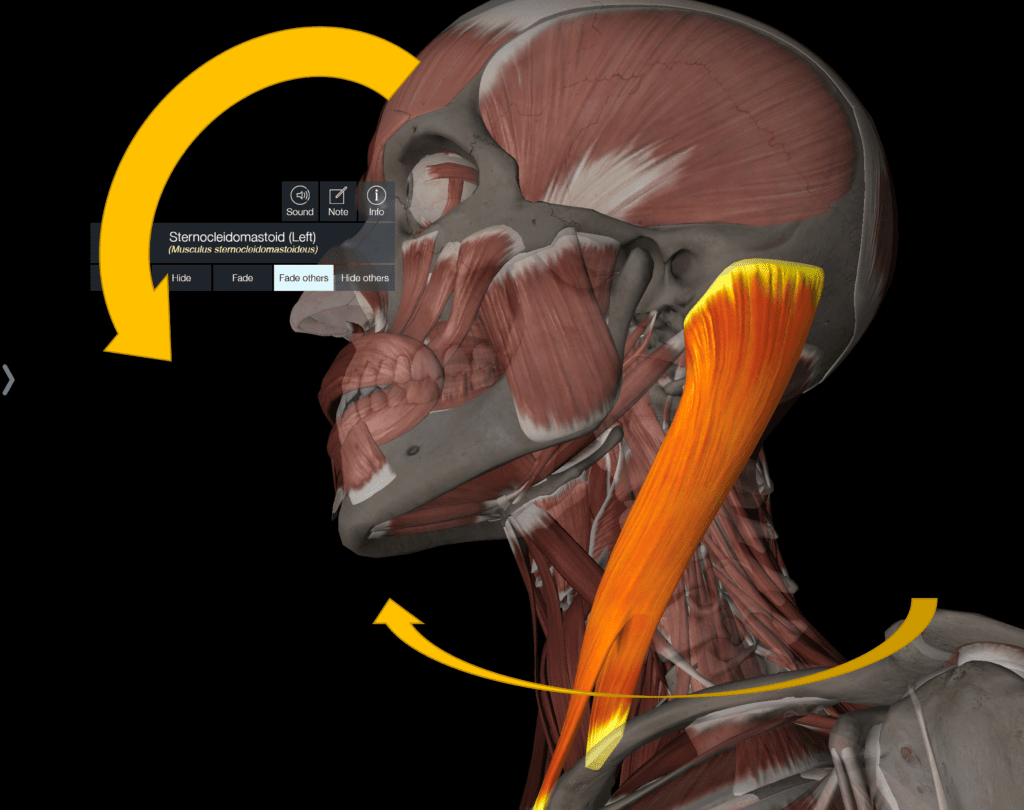

The muscle’s primary functions are to rotate and flex the head forward. It also acts to laterally bend the head on the neck. Note that the opposite SCM contracts to turn the head. For example, the right SCM turns the head to the left.

The SCM and Nerves

Sternocleidomastoid syndrome means that there are chronic problems with the SCM. One way to understand those issues is to learn about the relationship between this muscle and nerves.

The SCM is supplied by the spinal accessory nerve (CN XI). This nerve exits the skull and travels downward, also innervating the upper trapezius muscle. Given this skull exit point, in many patients with craniocervical instability, CN XI gets irritated by excessive skull on C1 motion, and this can cause the SCM and upper trapezius to go into spasm.

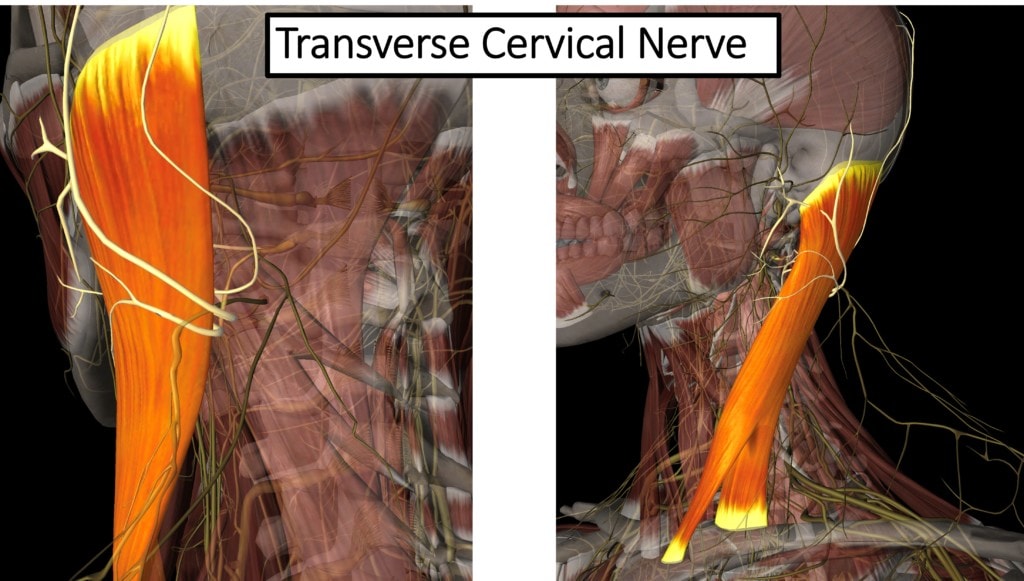

The transverse cervical nerve TCN), which originates from the cervical plexus (C1-C4), also exits at the back of the SCM. Because it traverses under this muscle, this nerve complex, which supplies sensation to the front of the neck, ear area, and back of the head, can become irritated if the SCM is in spasm. This often leads to pain in those specific areas. The TCN can be treated using ultrasound-guided platelet lysate hydrodissection, a procedure where the doctor places platelet growth factors around the nerve to help with nerve repair and function.

SCM Trigger Points

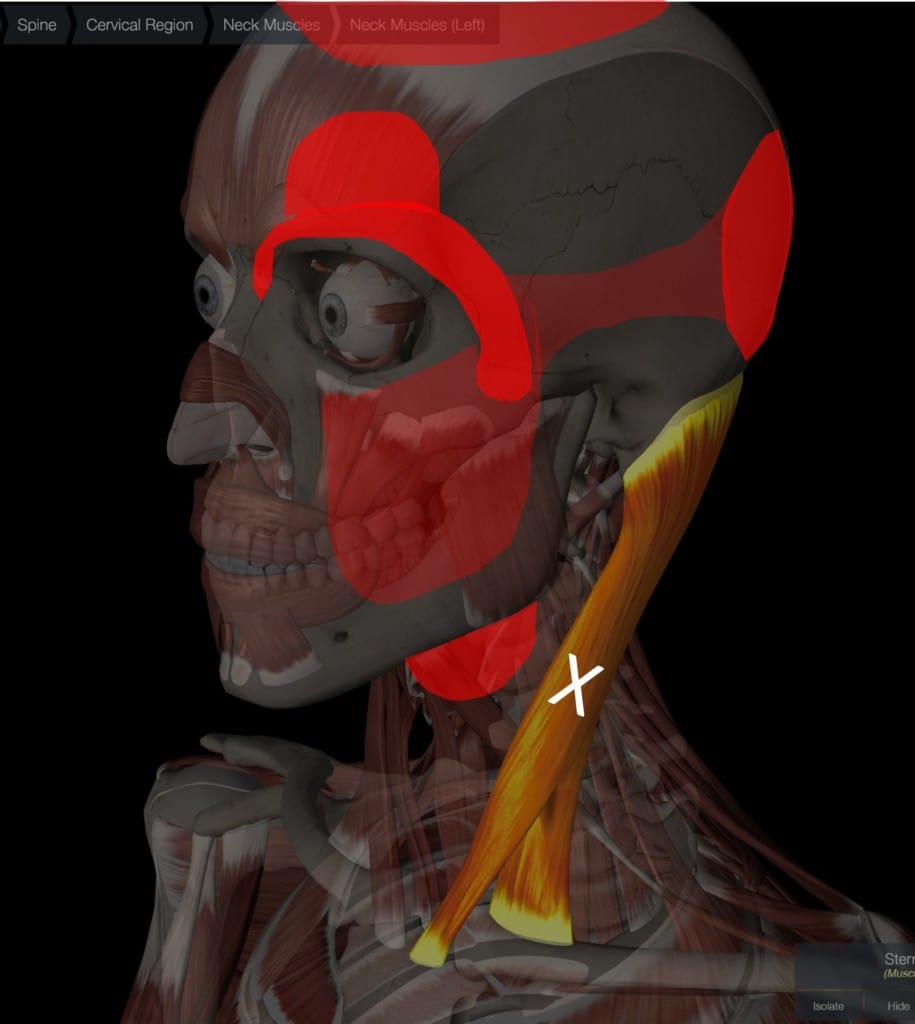

Sternocleidomastoid syndrome is often characterized by referred pain in other areas. Like all muscles, the SCM can develop tight, and non-contracting bands called trigger points that can refer pain elsewhere. For the SCM, the trigger point referral areas (shown above in red) are the eye and forehead, the back of the head (occiput), front of the neck, cheek, and side of the head. Trigger points can be treated by direct manual massage, dry needling, or platelet-poor plasma injection.

The SCM and Balance

Sternocleidomastoid syndrome is characterized by vertigo/dizziness and balance problems. While you wouldn’t think that a neck muscle is critical for balance, it turns out that the SCM has a role to play. In the late 50s and early 60s, NASA wanted to figure out what would happen to astronauts if they injured certain neck muscles during the immense g-forces of take off. Since the SCM was vulnerable, the space agency surgically cut the SCM muscles in primates (this is a horrible experiment that likely would never happen today). The primates had trouble walking and staying upright, confirming that the SCM plays a role in providing proprioceptive information to maintain normal balance. I bring this up because we have seen patients with SCM problems who have trouble maintaining normal balance (1-3).

It should also be noted that the position sensors in the SCM (proprioceptors) are linked to eye movement, similar to the upper neck. Meaning stimulating the SCM with vibration initiates specific involuntary eye movements (5). This connection between the eyes and neck is a key neurologic mechanism by which we can track an object that crosses our visual field by both moving the neck and eyes in a coordinated fashion which is known as “Smooth Pursuit”.

Torticollis

Some patients with sternocleidomastoid syndrome, have torticollis. Torticollis means that one SCM is in chronic spasm, causing the head to turn to the other side involuntarily. There is a body of literature that relates this problem to instability at the C1-C2 joint (non-traumatic rotatory subluxation that can happen after ENT surgery or Grisel’s Syndrome) (7). While there are other theoretical causes of torticollis, the connection between the upper neck and this disorder is important for my patients. Hence, treatment is either focused on the C1-C2 joint (meaning platelet-rich plasma injections to this joint) or if that fails, then the use of Botulinum Toxin (BoTox) injections into the SCM every 3 months.

CCI and Sternocleidomastoid Syndrome

Because the SCM is the primary rotator of the head and the C1-C2 facet joints allow the single largest amount of neck rotation (50% at this one joint), the two structures are intimately connected. For example, torticollis has been noted due to subluxation and instability of the C1-C2 joint, which was “fixed” via upper neck fusion of that joint (6).

Because of these connections, in patients with chronically tight SCMs (not quite a torticollis), we often look for issues at the C1-C2 joint and atlantoaxial instability (AAI or a sub-type of CCI). That means that the ligaments that hold the C1-C2 joint together and the head on the neck may be damaged and loose. Interventional orthobiologic procedures can restore normal neck stability without surgery.

The SCM and TMJ

The SCM muscle is overactive in patients with Temperomandibular Joint pain (4). This is likely because the SCM is a stabilizer of the anterior neck and one of the many strap muscles that act to help head stability when the TMJ is painful.

The upshot? The SCM is an interesting muscle that can cause lots of problems like headaches, dizziness, and pain referred to the face or neck. When that happens, the diagnosis of sternocleidomastoid syndrome is often made. Hence, learning about where this muscle is located and what can go wrong may help chronic neck pain patients get to a solid diagnosis and treatment.

____________________________________________________________

References:

(1) Missaghi B. Sternocleidomastoid syndrome: a case study. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2004;48(3):201-205.

(2) Sremakaew M, Treleaven J, Jull G, Vongvaivanichakul P, Uthaikhup S. Altered neuromuscular activity and postural stability during standing balance tasks in persons with non-specific neck pain. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2021 Dec;61:102608. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2021.102608. Epub 2021 Oct 13. PMID: 34662829.

(3) Hsu WL, Chen CP, Nikkhoo M, Lin CF, Ching CT, Niu CC, Cheng CH. Fatigue changes neck muscle control and deteriorates postural stability during arm movement perturbations in patients with chronic neck pain. Spine J. 2020 Apr;20(4):530-537. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2019.10.016. Epub 2019 Oct 28. PMID: 31672689.

(4) Choi KH, Kwon OS, Kim L, Lee SM, Jerng UM, Jung J. Electromyographic changes in masseter and sternocleidomastoid muscles can be applied to diagnose of temporomandibular disorders: An observational study. Integr Med Res. 2021 Dec;10(4):100732. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2021.100732. Epub 2021 May 16. PMID: 34141576; PMCID: PMC8185238.

(5) Han Y, Lennerstrand G. Eye movements in normal subjects induced by vibratory activation of neck muscle proprioceptors. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1995 Oct;73(5):414-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.1995.tb00299.x. PMID: 8751119.

(6) Akiyama Y, Takahashi H, Saito J, Aoki Y, Nakajima A, Sonobe M, Akatsu Y, Yamada M, Yanagisawa K, Shiga Y, Inage K, Orita S, Eguchi Y, Maki S, Furuya T, Akazawa T, Koda M, Yamazaki M, Ohtori S, Nakagawa K. Surgical treatment for atlantoaxial rotatory fixation in an adult with spastic torticollis: A case report. J Clin Neurosci. 2020 May;75:225-228. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.03.017. Epub 2020 Mar 13. PMID: 32178992.

(7) Iaccarino C, Francesca O, Piero S, Monica R, Armando R, de Bonis P, Ferdinando A, Trapella G, Mongardi L, Cavallo M, Giuseppe C, Franco S. Grisel’s Syndrome: Non-traumatic Atlantoaxial Rotatory Subluxation-Report of Five Cases and Review of the Literature. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2019;125:279-288. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-62515-7_40. PMID: 30610334.

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.