The Low Back Pain Circulus in Probando Experiment

What if you lied to your patients about what was wrong with them? Meaning, what if you told them there was nothing wrong when you as the doctor had no idea if that was accurate? What impact would that have on them? That was recently studied in an RCT on the biopsychosocial model of pain which is also a great example of circular reasoning. Let’s dig in.

The Biopsychosocial Model and Circulus in Probando

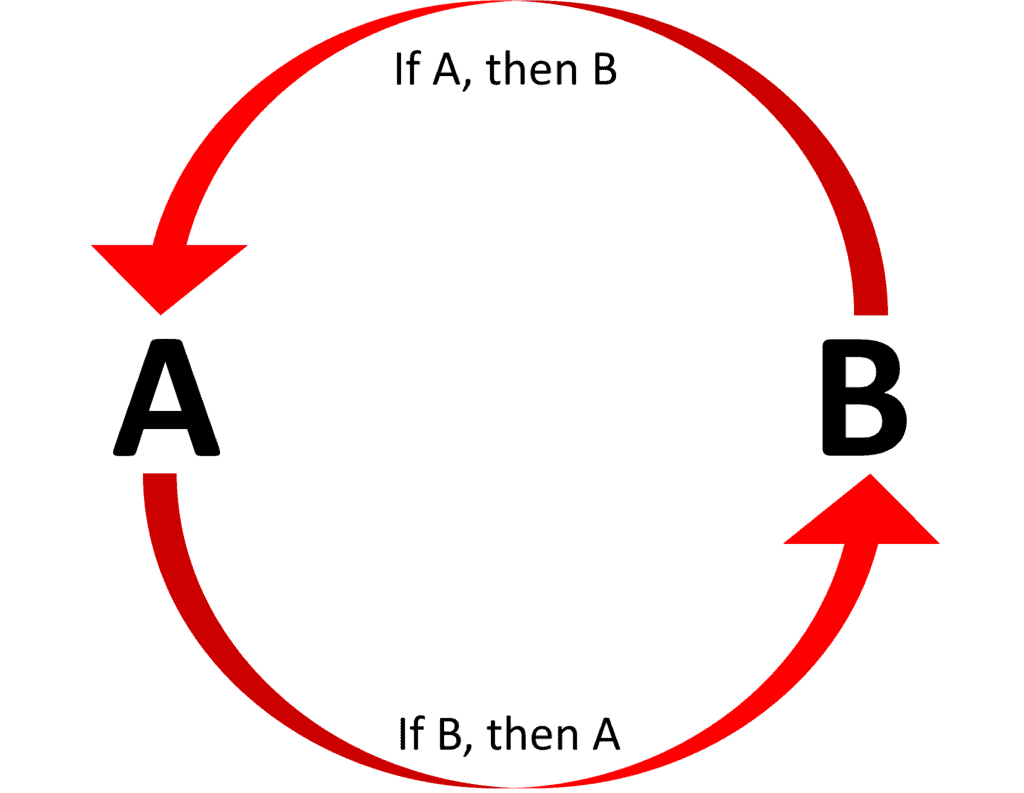

A circular argument, or what’s known in the world of logic as “Circulus in Proando” is when we begin with what we are trying to prove. Or said another way, the premises are just as much in need of proof as the conclusion and each is used to justify the other. So if A is true because B is true, B is true because A is true. For example, eighteen-year-olds have the right to vote because it’s legal for them to vote

One of the areas in pain medicine research that frequently uses circular reasoning is the biopsychosocial model (BPS model) of chronic pain. The idea behind this movement is that there is really no such thing as chronic pain due to damaged tissues and that this pain is created by how our brains interpret pain signals. Hence, psychological counseling to help patients reframe pain signals is all that’s required to get rid of the scourge of chronic pain.

A classic biopsychosocial experiment is also often circular. For example, patients with the highest perceived disability or more catastrophizing on a questionnaire take longer to recover. This data is then used to conclude that patients are magnifying their pain and that’s what’s causing delayed recovery. However, not considered is that patients who in fact are sicker often believe they are more disabled because they are in fact more medically disabled. For example, a patient with rheumatoid arthritis believes they are more disabled and will score high on a “catastrophizing questionnaire” because they really are more functionally disabled.

How do these experiments get past simple peer review when they always neglect to provide imaging or any modern diagnostic tests to locate a pain generator? That’s a question for which I have no polite answer.

What Implications Do These Experiments Have on Pain Medicine and Real Patients?

Patients in chronic pain are often desperate. They see specialist after specialist who has no idea what’s wrong. Some get test after test and image after image with nobody finding much of anything. Some finally spend the big bucks and end up at places like the Mayo clinic, in hopes that these vaunted institutions know more than their doctors. However, in my direct experience, most are sadly disappointed.

Because the biopsychosocial model of pain uses invalid circular reasoning, I’ve largely ignored it as pseudoscientific. However, it has nonetheless spawned an entire cult of providers who have taken over entire university rehab departments. One example is Mayo Clinic, where I have seen countless patients after they have failed their Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE) programs which are based on the biopsychosocial model (see this link for the Mayo PNE video shown above). These patients are taught that there is nothing wrong with them and that they need to reconceptualize their pain signals. Obviously, the success of such programs is self-fulfilling with the providers believing they are wildly successful and the patients quickly figuring out what to tell providers to end this treatment nightmare. They then end up in my office, still in pain and trying to find answers. We often find real diagnoses in these patients that were missed by Mayo and when specific treatments are applied these patients get better.

IMHO, the idea that serious pain medicine experts can continue to ignore the biopsychosocial model and PNE is problematic. Our patients are getting bombarded with this stuff and there is an entire academic push to declare chronic pain as merely a function of our modern society and bad messaging delivered by the PNE uninitiated. As an example of this trend, let’s delve into a recent BPS/PNE study that uses the Circulus in Probando argument.

Lying to Patients About What’s Wrong with Them

One of the main tenants of the BPS/PNE model is that bad providers tell chronic pain patients that there is something seriously wrong. This messaging then sets these patients on a path of chronic pain and care-seeking behavior. Hence, if we could educate medical providers to avoid telling patients that they have real medical problems, we can prevent new chronic pain patients from being minted.

Recently, in the world’s BPS and PNE capital, Australia, researchers randomized 1,375 patients with and without low back pain as follows:

“Participants received one of six labels: ‘disc bulge’, ‘degeneration’, ‘arthritis’, ‘lumbar sprain’, ‘non-specific LBP’, ‘episode of back pain’. The primary outcome was the belief about the need for imaging.”

So basically the experiment looked at how patients were messaged about what was wrong with their low back by either using language that suggested possible structural problems:

- ‘disc bulge’, ‘degeneration’, ‘arthritis’

Or language which suggested that the problem was minor:

- ‘lumbar sprain’, ‘non-specific LBP’, ‘episode of back pain’

What did the researchers find? That using the structural language with low back pain patients caused them to have lower expectations for recovery and caused them to be 25% more likely to want imaging or a second opinion when compared to the labels suggesting the problem was minor. However, there were no differences noted in the ability of the two groups to be active or their ability to work.

So what was proved? Telling patients that they are less injured means that some will believe what you tell them. This seems like a classic case of circular reasoning as no concrete conclusions can be drawn.

For example, if a qualified mechanic tells you there’s nothing wrong with your car despite you complaining that it frequently stalls, some people will believe the mechanic. However, that tells us little about whether the car really had a problem and whether some people believe their car to be more damaged than it really is. In fact, the mechanic telling you that your car has no issue doesn’t change the rate at which the cars in this experiment will eventually finally break down and no longer run.

What can be concluded from this Australian BPS study? The implication is that if doctors tell back pain patients who are seeking care that there is nothing seriously wrong, they can help reduce the need for imaging and second opinions. However, what happens to these patients who are told nothing is wrong when something is later discovered on imaging that matches their complaints? For example, did the later MRI diagnosis of a structural problem cause them to use fewer healthcare resources or more resources because they were pissed off because they had obviously been lied to?

The upshot? BPS and PNE “research” is often amusing to physicians who treat patients with chronic pain. While there are always those patients who could benefit from a good discussion about how they need to get out and live their lives and ignore every ache and pain, when this stuff becomes mainstreamed and used in most chronic pain patients, it becomes more of a hindrance to finding out the real diagnosis and helping the patient. In addition, the fact that unscientific circular reasoning often lies at the heart of the BPS and PNE “scientific” literature and that large university rehab departments have swallowed this fake “red pill” is a serious disservice to most chronic pain patients.

______________________________________________________

References:

(1) O’Keeffe M, Ferreira GE, Harris IA, Darlow B, Buchbinder R, Traeger AC, Zadro JR, Herbert RD, Thomas R, Belton J, Maher CG. Effect of diagnostic labelling on management intentions for non-specific low back pain: A randomized scenario-based experiment. Eur J Pain. 2022 Aug;26(7):1532-1545. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1981. Epub 2022 Jun 21. PMID: 35616226.

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.