What Does Tommy John Surgery Research Show?

Yesterday I was working out on an elliptical and watching the TV in the health club. A feature called ESPN Sports Science was on about Tommy John surgery in major league pitchers and kids. One of the more disturbing things was that the commentators were arguing back and forth that an injured pro pitcher was waiting before getting the surgery. One talking head was on the side that it was ridiculous that the pitcher would wait, the other was obviously a retried pitcher who said he let his heal and it was fine. The twilight zone quality of the argument was the vehemence of the one commentators that Tommy John Surgery was a foregone conclusion. So is there much Tommy John surgery research to show that this procedure is so good that pitchers must be forced into it?

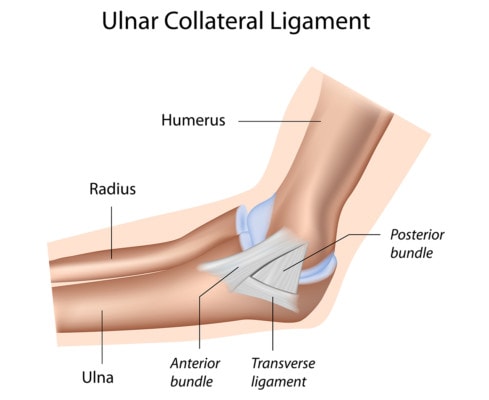

Alila Medical Media/Shutterstock

Tommy John surgery is a surgical reconstruction of an injured ulnar collateral ligament (UCL). The UCL is the “duct tape” that holds the inside of the elbow stable. When you throw, you place force on this ligament as you whip the ball. So the injury that leads to a surgical reconstruction of the ligament is a partial or complete tear. What was really surprising in this ESPN piece (that I’m sure 99% of viewers took as gospel) was that nobody really discussed that other research has shown that the elbow UCL ligament gets injured more often when there’s poor range of motion at the shoulder. So the first way to deal with the injury in the elbow is to look at what’s not happening in the shoulder.

So is there Tommy John surgery research to show that this very invasive procedure involving drilling holes in the elbow and stringing a hamstrings tendon to take the place of the UCL ligament actually works? First, there’s not a single randomized controlled trial that I can find that compares the effectiveness of the surgery to doing nothing. So despite the back and forth on ESPN that the pitcher was an idiot for not immediately pulling the trigger on the surgery, no high level research shows that the surgery is effective. So score 1 for our stubborn pitcher, 0 for ESPN. In fact, our pitcher could have been very concerned by this study, that shows that despite reasonably high rates of return to pitching, pitching performance goes down after surgery. ERA goes down, WHIP (Walks and Hits per Innings Pitched) goes up, and the number of innings pitched goes down. Why? Isn’t the surgery magic in repairing the torn ligament? Nope. The reconstructed ligament will never have the normal bio mechanics of the original equipment.

One could make the argument that the pitcher wasn’t throwing all that well before the surgery, so what does he have to lose? Well based on a study from June, quite a bit. In this research of 17 pitchers whose grafts were well maintained (meaning that they hadn’t ruptured), only 53% got back to pitching! Even this study, which was published by advocates for the surgery paints a picture different than what most people believe about the procedure. Career longevity was only three years after return to play, with major and minor league baseball players pitching longer than college or high school players. This last part is a bit disturbing, as I don’t know many college or high school pitchers who would opt for this surgery who don’t have big dreams of becoming a major league pitcher, as the only rationale for the surgery is to keep pitching (i.e. if you retire at that point your elbow is unlikely to hurt). Hence despite the study’s conclusions, it would seem likely that this inversion of recovery (older patients paradoxically doing better than younger ones) is more due to the motivating factors involved in professional play (i.e. money). Which begs the point of how accurate self-report by pitchers is concerning return to play (on which advocate studies heavily rely). Another amusing issue about this study is that while most players didn’t retire because of their bad elbow, many retired because of a bad shoulder (see discussion above about this elbow condition being caused by the shoulder)! Score is stubborn pitcher 2, ESPN 0.

The upshot? Tommy John surgery is major reconstructive surgery. When detailed analyses are performed of baseball statistics rather than self report of pitching abilities by pitchers who desperately want to pitch, the surgery reduces performance. In addition, many pitchers who have the surgery never make it back to high levels of play. Finally, the injury is a shoulder problem masquerading as a elbow issue, so aggressively operating on elbows may be ill advised. In addition, outside of studies by advocates for the surgery, we have no controlled trials showing that it’s better than no surgery. So after my analysis of what’s out there, this pitcher who was berated for not immediately joining the “Tommy John Surgery Club” may have been much smarter than the commentators!

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.