When Not to Have Rotator Cuff Surgery?

Are you wondering when not to have rotator cuff surgery? These days, more people are opting to skip this surgery. Who should do that and who really needs the surgery? I’ll also cover a patient here who decided to skip the surgery despite a rotator cuff tear and is back to full activities. Let’s dig in.

What is A Rotator Cuff Tear?

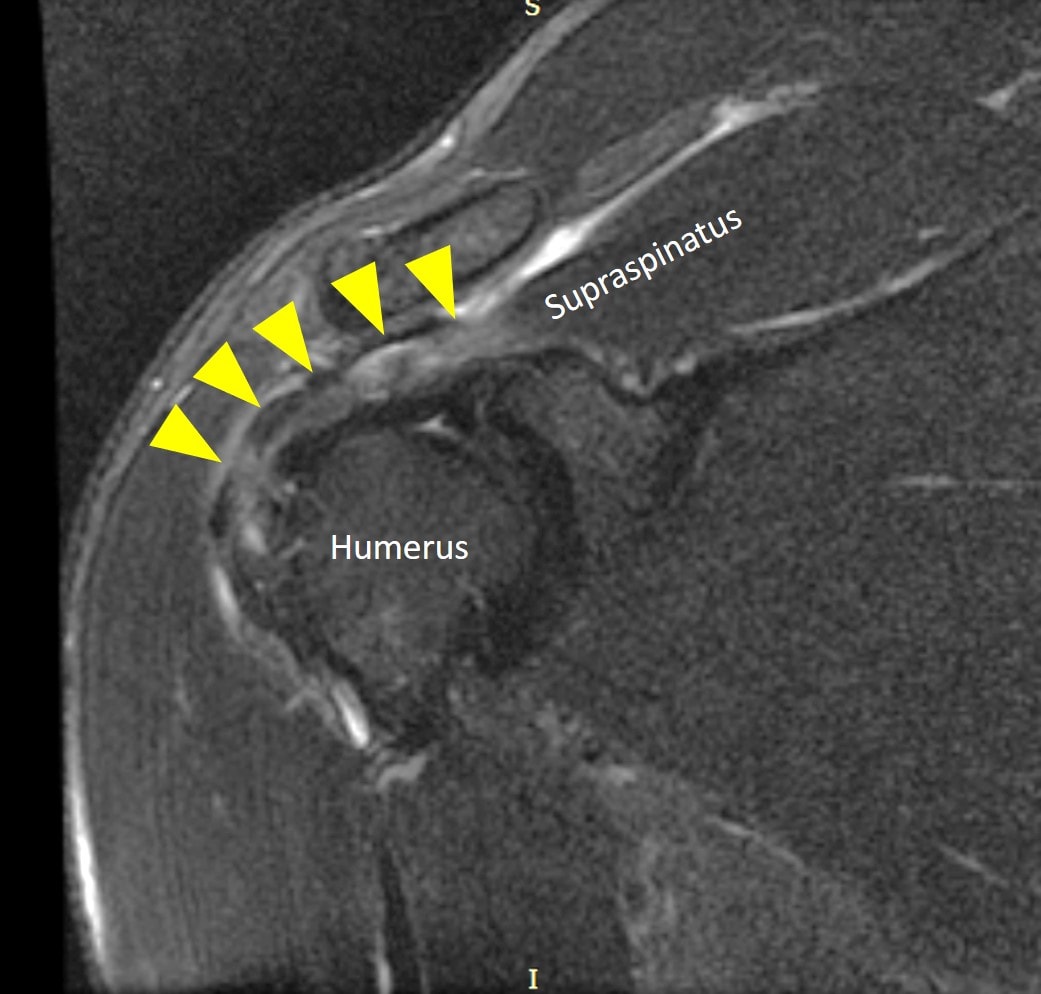

The rotator cuff muscles and tendons surround the shoulder joint and move it as well as stabilize it. There are four muscles which include, from front to back, the subscapularis, the supraspinatus, the infraspinatus, and the teres major/minor. The tendons can get injured or torn due to trauma or age. This can cause pain with shoulder movement and if physical therapy doesn’t help, surgery is often recommended.

How Does Rotator Cuff Surgery Work?

The tear in the rotator cuff tendon is often sewn together surgically. If the tendon has broken off the area where it inserts on the bone, anchors can be used to adhere the tendon back to the bone. Other procedures are often also performed such as acromioplasty. This is where one of the bones of the shoulder is shaven down to make more room for the rotator cuff.

When Not to Have Rotator Cuff Surgery?

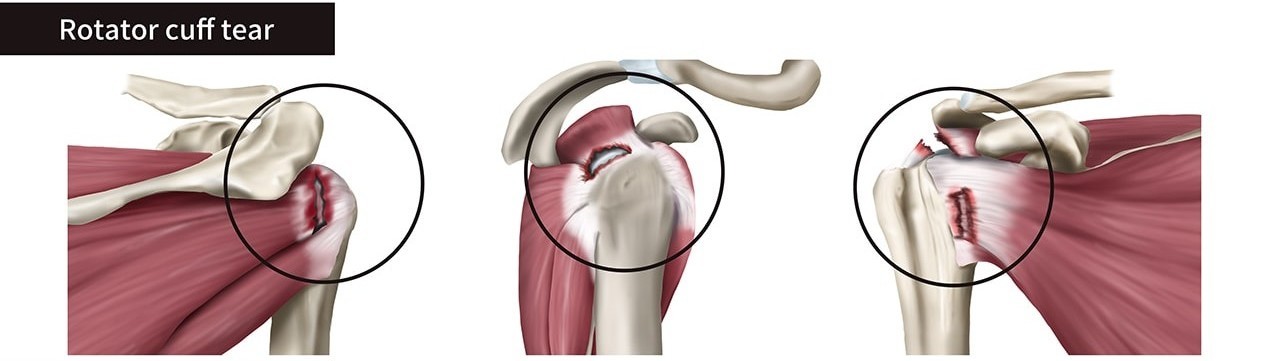

There are three different types of rotator cuff tears:

- Partial Tear. This is where a part of the tendon has been torn, usually the top (bursal side) or bottom (articular side). The partial tear can also be inside the tendon, in which case it’s called interstitial or intrasubstance.

- Complete Non-retracted Tear. This type has many small tears throughout the whole tendon, but it’s still held together as one piece. Regrettably, many MRI reports don’t point this type out clearly.

- Complete Retracted Tear. This is also called a massive rotator cuff tear. Basically, the tendon is completely torn and pulled back like a rubber band.

Traditionally, all three of these types of tears were surgical candidates. However, more recently, research has shown that surgery for a partial tear produces no better outcomes than just physical therapy (1). Hence, if you have a partial tear, this is the clear definition of when not to have surgery.

Complete retracted or massive tears are tricky. One problem is that the retear rate is very high, with about 6 in 10 of these rotator cuff tendons tearing again after surgical repair (6). One way to avoid retears is by having your own bone marrow stem cells injected into the surgically repaired site (3). This seems to reduce that problem by about half.

Finally, the middle category of a complete non-retracted tear is really interesting. For this type of tear, many surgeons recommend surgery. However, research shows that surgery isn’t better than no surgery (2). In addition, there’s also information showing that injecting PRP or bone marrow concentrate into the tear can help avoid surgery (4,5). How does that work? By stimulating the tendon to heal itself. Below is a video that shows that newer procedure:

How Long Can You Wait to Have Rotator Cuff Surgery?

Generally, after an acute tear, you can wait a few months before rotator cuff surgery. Having said that, many rotator cuff tears have been there for many years before they are surgically repaired.

___________________________

References

(1) Nazari G, MacDermid JC, Bryant D, Athwal GS. The effectiveness of surgical vs conservative interventions on pain and function in patients with shoulder impingement syndrome. A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0216961. Published 2019 May 29. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0216961

(2) Khatri C, Ahmed I, Parsons H, Smith NA, Lawrence TM, Modi CS, Drew SJ, Bhabra G, Parsons NR, Underwood M, Metcalfe AJ. The Natural History of Full-Thickness Rotator Cuff Tears in Randomized Controlled Trials: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2019 Jun;47(7):1734-1743. doi: 10.1177/0363546518780694. Epub 2018 Jul 2. PMID: 29963905.

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.