Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL) Tears: Everything You Should Know

Medically Reviewed By:

Lateral collateral ligament (LCL) tears occur when the ligament on the outer side of the knee becomes overstretched or torn. Common causes may include trauma, sudden movements, and sports accidents. Symptoms often include pain, swelling, and knee instability, which may interfere with daily activities. Without treatment, LCL injuries may contribute to long-term knee instability and impaired function.

Isolated LCL injuries are uncommon, accounting for only 2% of all knee ligament injuries. However, they often occur alongside other ligament or knee injuries, particularly in individuals participating in high-impact activities.

Relying solely on pain medications may temporarily relieve symptoms but does not address underlying musculoskeletal issues. In some cases, this may contribute to ongoing joint instability or the progression of certain conditions.

Physicians in the licensed Regenexx network offer non-surgical options designed to support the body’s natural repair processes and improve function. In some cases, these approaches may help individuals explore alternatives to surgery depending on their condition and physician recommendations.

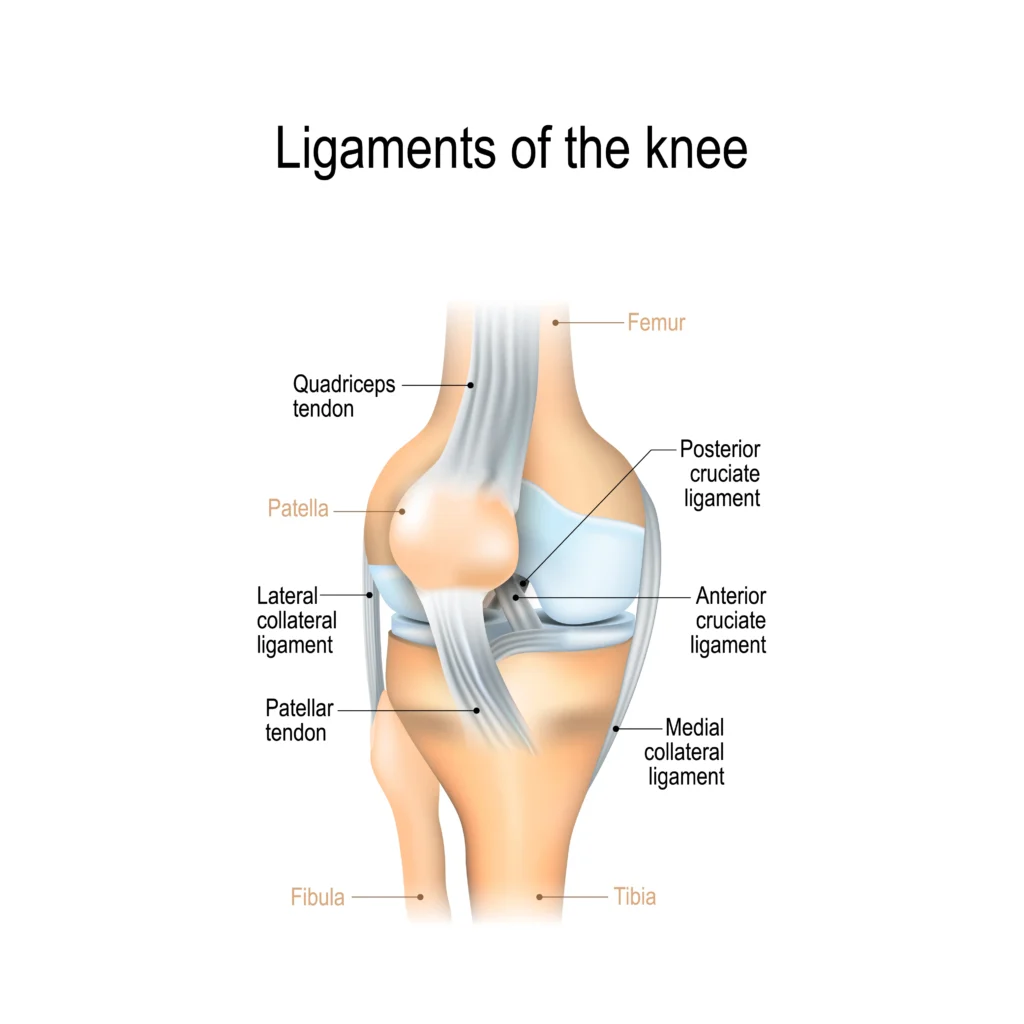

Looking Into The Anatomy Of The Knee

The knee is a complex joint that connects the thigh bone (femur) to the shinbone (tibia). It plays a crucial role in supporting body weight and redistributing forces during movement. Thanks to its hinge-like structure, it facilitates the straightening and bending of the leg, which are key motions for activities like walking, running, and jumping.

Four primary ligaments stabilize the knee by connecting bone to bone:

- Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL): The ACL is located at the center of the knee. It helps keep the tibia aligned with the femur, which may help prevent injuries like dislocations. The ACL also provides rotational stability, meaning it helps limit excessive inward rotation of the knee.

- Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL): The PCL is also centrally positioned in the knee joint. It helps prevent the tibia from sliding backward and stabilizes the knee during movements like walking downhill.

- Medial collateral ligament (MCL): The MCL is positioned on the inner side of the knee. It helps prevent excessive inward bending and supports joint stability during side-to-side movements.

- Lateral collateral ligament (LCL): The LCL is located on the outer side of the knee. It helps prevent the knee from bending excessively outward and provides lateral stability.

The LCL is critical for maintaining knee stability during rapid direction changes or lateral movements. An LCL tear may compromise this stability, potentially impacting side-to-side movement and increasing susceptibility to additional injuries.

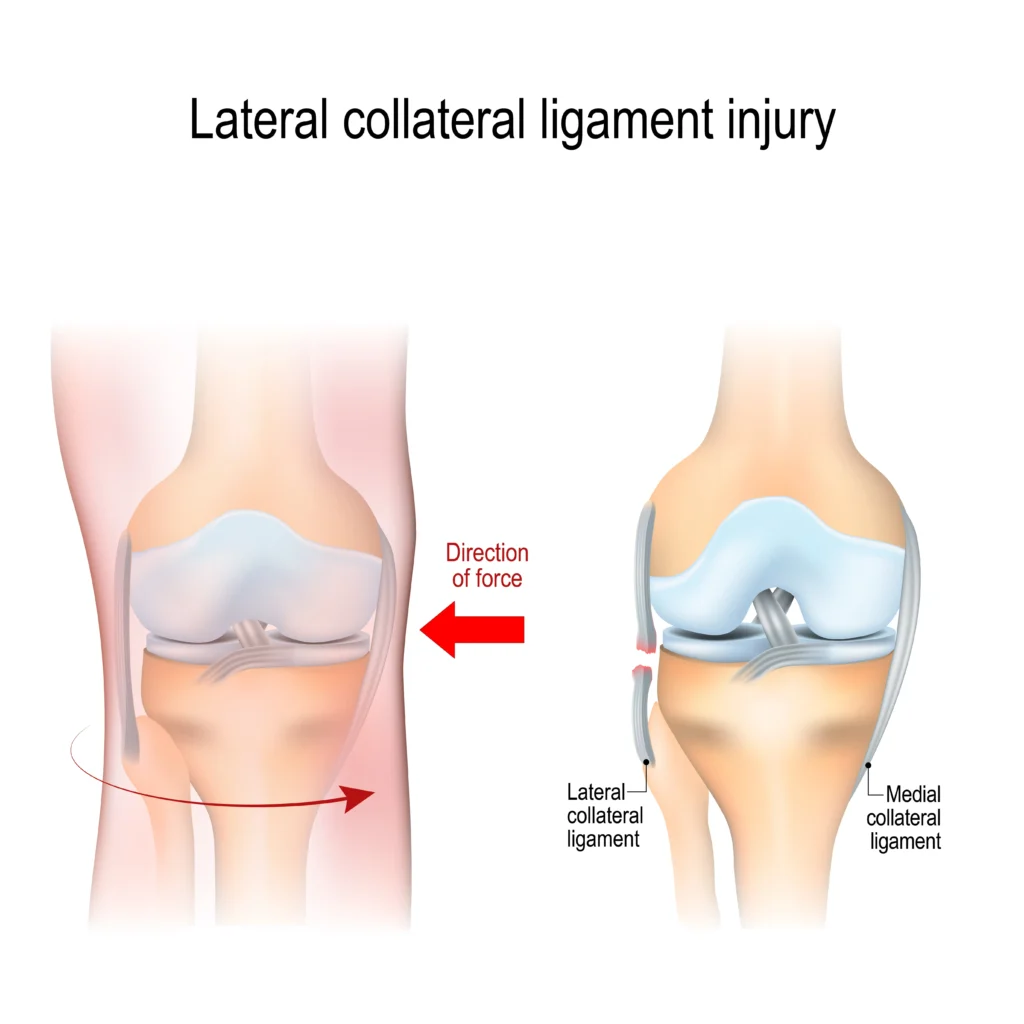

What Are LCL Tears?

LCL tears occur when the lateral collateral ligament becomes torn or overstretched, often due to excessive external pressure, rapid direction changes, or landing improperly on one leg.

While it is uncommon to injure just the LCL, this type of injury often occurs in conjunction with other knee injuries, such as ACL tears, fractures, or dislocations. LCL tears have been reported in up to 16% of knee injuries involving other ligaments. Depending on the severity, LCL tears may impair knee stability and function, potentially leading to pain, swelling, and difficulty bearing weight.

Where In The Knee Does A Torn LCL Occur?

The LCL is a cord-like ligament located on the outer side of the knee. It connects the femur (thighbone) to the fibula (the smaller bone of the lower leg). Its primary role is to help stabilize the outer side of the knee joint, limiting excessive outward bending.

Classification Of LCL Injuries

LCL injuries are classified into three grades based on severity:

- Grade I: Mild sprain. In a Grade 1 sprain, the ligament is overstretched but intact. Symptoms include mild pain, tenderness, and slight swelling. This type of damage has little to no impact on knee stability.

- Grade II: Partial tear. In a partial tear, only some fibers are affected, causing the structure to lose its strength and elasticity. However, the ligament remains attached to the thigh bone and lower leg bone. Symptoms include pain on the outer side of the knee, swelling, and mild instability.

- Grade III: omplete tear. In a complete tear, all ligament fibers are impacted. This can be:

- Non-retracted, when the ligament fibers still attach the bones together

- Retracted, when the structure detaches from the thigh bone or lower leg bones.

Symptoms include severe pain and knee instability.

Common Causes Of A Torn LCL

LCL tears may result from sports accidents or direct blows to the knee. Some demographics may have an increased likelihood of experiencing these injuries. These include:

- Physically active individuals: Athletes in high-impact sports involving pivoting or quick direction changes—such as soccer, tennis, or gymnastics—may be at higher risk. A 2021 study found that in recreational alpine skiing, ACL injuries were among the most common knee injuries and often occurred alongside LCL tears.

- Individuals with prior injuries: Research suggests that people who have previously sustained injuries to their knees, ankles, or hips may have a higher likelihood of experiencing LCL tears. Knee injuries that involve acute blows to the inside of a straightened knee or excessive outward bending without direct contact—such as during pivoting—may contribute to LCL damage.

- People with additional risk factors: These may include occupations involving frequent knee strain, age-related ligament changes, muscle imbalances, poor conditioning, and biological factors such as sex-related anatomical differences.

Direct causes of LCL tears include the following:

Direct Blow To The Knee

The most common cause of an LCL tear is a high-energy blow to the inside of the knee. The excessive force may push the knee outwards, causing the LCL to overstretch or tear.

This type of acute injury often results from accidents, such as a fall or a collision in contact sports. The sudden impact may also affect other knee structures, such as the medial collateral ligament (MCL), anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) or meniscus.

Contact Sports

Tackles, collisions, rapid direction changes, and pivoting movements—common in sports like football, soccer, or rugby—may increase the likelihood of LCL tears. Depending on the force and angle of impact, these injuries can sometimes involve multiple ligament tears.

A 2020 study on men’s professional soccer over 17 seasons found that approximately 58% of LCL injuries resulted from direct contact. Players experienced an average recovery period of about two weeks, with midfielders most commonly affected. Nearly half (45%) of the injuries were classified as Grade II, or moderate in severity.

Abrupt Changes Of Direction When In Motion

The LCL helps stabilize the knee during lateral (side-to-side) movements. Sudden directional changes may place significant stress on the ligament, potentially increasing the risk of overstretching. This risk may be higher in sports like basketball or tennis, where quick pivots are frequent.

Repeated stress from such movements could also contribute to degenerative changes in the ligament over time.

Twisting Or Pivoting On One Foot

Twisting or pivoting motions may place the knee under excessive rotational forces, which can overstretch the LCL. These movements are common in sports like skiing, gymnastics, or dancing and may contribute to acute injuries if the rotational force exceeds what the ligament can withstand.

Twisting injuries often involve other knee structures, such as the ACL or meniscus.

Jumping Or Landing Badly

Landing with the knee in an awkward position—such as outward bending—can cause uneven force distribution across the joint. This stress may overstretch or tear the LCL.

Torn LCL Symptoms

The specific location and intensity of symptoms from an LCL tear may vary based on the injury’s severity and may include:

- Pain: Pain is usually felt on the outside of the knee. Grade I injuries typically cause mild discomfort, while more severe tears may result in intense pain, particularly during lateral movements.

- Bruising: Damage to blood vessels near the injured area may cause bruising, often appearing along the outer knee.

- Swelling: Swelling may occur due to the body’s inflammatory response to tissue damage, causing fluid buildup around the knee joint. This can sometimes limit movement and increase discomfort.

- Instability When Moving the Knee from Side to Side: LCL injuries may affect the ligament’s ability to stabilize the knee when moving from side to side. Patients may experience a feeling that the knee will “give out” or buckle outward.

- Abnormal Range of Motion: A torn LCL may disrupt normal joint mechanics. Patients may experience restricted movement due to swelling. Ligament instability could also cause the knee to feel loose.

- Numbness or Weakness in the Foot: Knee injuries may affect nearby nerves, such as the peroneal nerve. This could potentially disrupt motor and sensory signals, causing numbness or weakness. A 2021 study suggests that LCL injuries may contribute to foot drop, a condition that affects the ability to lift the front part of the foot, impacting walking mechanics.

- Side-Of-Knee Pain: Pain on the side of the knee may result from ligament injuries, iliotibial (IT) band syndrome, or meniscus issues. Accompanying symptoms can include tenderness, swelling, and discomfort, often worsening with movement or prolonged activity. Read More About Side-Of-Knee Pain.

- Back-of-Knee Pain: Pain behind the knee may result from conditions such as tendonitis, a Baker’s cyst, or hamstring strain. It may cause stiffness, swelling, or discomfort, often worsening with movement or prolonged activity. Read More About Back-Of-Knee Pain.

- Knee Hyperextension: Knee hyperextension occurs when the knee bends backward beyond its normal range, often due to ligament laxity or injury. It may cause pain, swelling, and instability, increasing the risk of further joint damage. Read More About Knee Hyperextension.

Diagnosing A Torn LCL

Diagnosing an injury to the LCL may be complex, particularly if other knee components are affected. Physicians use a combination of physical examinations, medical history evaluations, and imaging tests to assess the extent of the injury.

Physicians in the licensed Regenexx network perform comprehensive evaluations, which may include SANS methodology. These evaluations examine the body in motion, review imaging (such as MRI or X-ray), and may include real-time ultrasound to observe joint mechanics.

Together, these methods provide a comprehensive picture of the injury’s root causes, its impact on function, and its contributing symptoms.

Physical Examination

A physical examination helps evaluate how knee function may be affected. Physicians perform specific tests to detect looseness or instability in comparison to the healthy knee, which may suggest LCL damage. These tests include:

- Varus stress test: Pressure is applied to the outer side of the knee with the leg bent slightly, then straight. Increased looseness may suggest LCL damage. Performing this test on a straight leg may also help identify damage to other knee structures.

- External rotation recurvatum test: While the patient lies face up, the physician applies pressure above the knee and rotates the shin. A greater backward bend in one leg compared to the other may suggest LCL issues.

- Reverse pivot shift: With the patient lying face down, the physician bends and straightens the knee while assessing for clicking sounds, which may indicate ligament damage.

- Dial test: The physician rotates the leg outward at two angles while the patient lies face down. Excessive rotation may suggest ligament looseness.

Medical History

Evaluating a patient’s medical history helps physicians identify past injuries or conditions that could be contributing to pain. These may include past blows to the knee or nearby joints, anomalies in knee structure, and gait problems.

For example, research suggests that having a varus knee, or being “bow-legged,” may affect how loads are distributed across the joint. Over time, this may influence the structural integrity of the lateral side of the knee, where the LCL is located.

Imaging Tests

Imaging tests provide detailed insights into the knee joint:

- MRI: An MRI is commonly used to assess soft tissue injuries, such as partial or complete LCL tears and damage to related ligaments.

- X-ray: An X-ray is primarily used to assess hard tissues like bones and may help identify issues such as fractures or ligament avulsions (where a small piece of bone is pulled away from the main part of the bone).

Can LCL Tears Heal On Their Own?

An LCL tear may heal naturally depending on the severity of the injury. A 2022 study suggests that recent research shows Grade I and Grade II isolated LCL tears may have the potential to heal over time.

Time, rest, and physical therapy may support recovery for some LCL tears; however, the body’s natural healing ability varies, and in some cases, additional support may be beneficial. That’s where physicians in the licensed Regenexx network may help.

Interventional orthobiologics are designed to concentrate the body’s biologic materials, and because they are an injection-based treatment, they offer a non-surgical option that may help support the recovery process.

Common Treatment Options

Conventional treatment options for LCL tears may vary depending on the injury severity.

- Rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE) – This at-home approach is commonly used to help reduce swelling and pain by managing fluid buildup around the injured area. However, it may also temporarily reduce blood flow to the knee, which, according to recent research, could potentially slow down healing.

- Knee Braces and Splints: Supportive devices like crutches and a knee brace may help reduce the amount of weight placed on the knee. A knee brace or immobilizer may also provide additional stability while walking or standing.

- Physical Therapy: A structured physical therapy program is often recommended to help improve strength, flexibility, and function of the knee joint, supporting recovery.

- Surgery: Surgery may be considered for severe Grade III tears or when other parts of the knee are also affected. Common surgical approaches include:

- LCL repair: Reattaching torn ligaments to the bone.

- LCL reconstruction – Replacing the damaged ligament with tissue sourced from other ligaments, known as a graft.

- Arthroscopic Knee Surgery – Arthroscopic knee surgery is a less invasive procedure than open surgery, used to diagnose and treat knee issues like meniscus tears or ligament injuries. It involves small incisions and a camera for visualization. Risks and recovery vary. Read More About Arthroscopic Knee Surgery.

A 2020 study suggests that Grade I and Grade II tears are commonly treated conservatively, while surgery is generally considered for severe Grade III tears and injuries involving other knee ligaments. However, this approach may not apply to all cases.

A 2010 study conducted on National Football League athletes reported that treating isolated Grade III LCL tears without surgery may result in a faster return to play and could reduce risks for the player.

In addition to these conventional therapies, interventional orthobiologics offered by physicians in the licensed Regenexx network may help address symptoms of LCL tears. Procedures using Regenexx injectates help harness the body’s natural repair processes, offering an alternative to surgery and may help reduce the need for prescription drugs, such as opioids.

How The Regenexx Approach Supports Patients With Torn LCLs

Physicians in the licensed Regenexx network are trained in performing interventional orthobiologic procedures. These procedures involve injections of customized concentrations of healing agents, including platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and bone marrow concentrate (BMC) that contains the patient’s own biologic materials, such as mesenchymal stem cells.

Using imaging guidance, these injections are precisely delivered into the injured area. This approach is designed to support the body’s natural repair processes and may help reduce the need for surgery.

Regenexx SD Injectate

Procedures using Regenexx SD (same day) injectate follow a patented protocol that utilizes bone marrow concentrate (BMC), which contains the patient’s own mesenchymal stem cells. The cell-processing method used in Regenexx is designed to achieve a high concentration of stem cell-containing bone marrow, following proprietary techniques.

Regenexx SCP Injectate

The Regenexx-SCP (Super Concentrated Platelets) injectate procedure follows a proprietary lab process designed to refine platelet-rich plasma (PRP). In this process, a patient’s blood is drawn, processed to isolate platelets and growth factors, and then concentrated for injection into the knee area using advanced imaging guidance.

Procedures using Regenexx-SCP injectate are designed to provide a high concentration of platelets and growth factors, following a patented protocol used by physicians in the licensed Regenexx network.

Regenexx PL Injectate

Regenexx-PL (platelet lysate) injectate is a highly specialized derivative of platelet-rich plasma (PRP), processed using Regenexx’s proprietary lab techniques. This formulation is designed to deliver growth factors in a refined form.

Physicians in the licensed Regenexx network may use Regenexx-PL injectate alone or in combination with other interventional orthobiologic procedures, such as Regenexx-SCP or bone marrow concentrate, depending on a patient’s condition and treatment plan.

Take Charge Of Your Knee Health Today

LCL injuries can impact your daily mobility and sports career. Get in touch with a physician in the licensed Regenexx network to find out if you are a candidate for interventional orthobiologics.

Get started to see if you are a Regenexx candidate

To talk one-on-one with one of our team members about how the Regenexx approach may be able to help your orthopedic pain or injury, please complete the form below and we will be in touch with you within the next business day.

Medically Reviewed By: