ITB Release Surgery – What Orthopedic Surgeons Won’t Tell You

Tight ITBs (iliotibial bands) are a cottage industry now. There are many cool devices designed to loosen up your ITB and a trip to any local gym will always turn up a few individuals aggressively stretching this area. When these efforts fail to produce results, some people turn to ITB release surgery. And while ITB release surgery may seem like a reasonable concept on the surface, the negative implications for the knee joint can be significant.

Iliotibial Band Release Surgery = Bad Idea

The ITB is a tight band that runs down the side of the leg from the hip to the knee. The structure supports the lateral stability of the spine, hip, and knee and has fascial connections that extend all the way down to the bottom of the foot. Tightness here is common, so physical therapists, personal trainers, and athletic trainers usually recommend that patients stretch or roll out this area. However, many athletes turn to ITB release surgery looking for a solution to this problem.

ITB release surgery involves the surgeon cutting a piece of the tendon out (usually near its attachment at the side of the knee), with the goal of weakening the tendon a bit so it lengthens and then hopefully heals over. While this typically accomplishes the goal of lengthening the tendon and reducing the tightness, this structural change to a delicately balanced system can have some real downside consequences.

Had ITB Surgery and Now Regrets It

Case in point is the runner I evaluated this past week who had the surgery and now regrets it. The patient is an avid weekend warrior who runs, bikes, hikes, and cross country skis. He had an ITB release surgery several years back that at first seemed successful. However, shortly thereafter he had a medial (inside) meniscus tear in the same knee. He didn’t connect the dots at the time and neither did his surgeon.

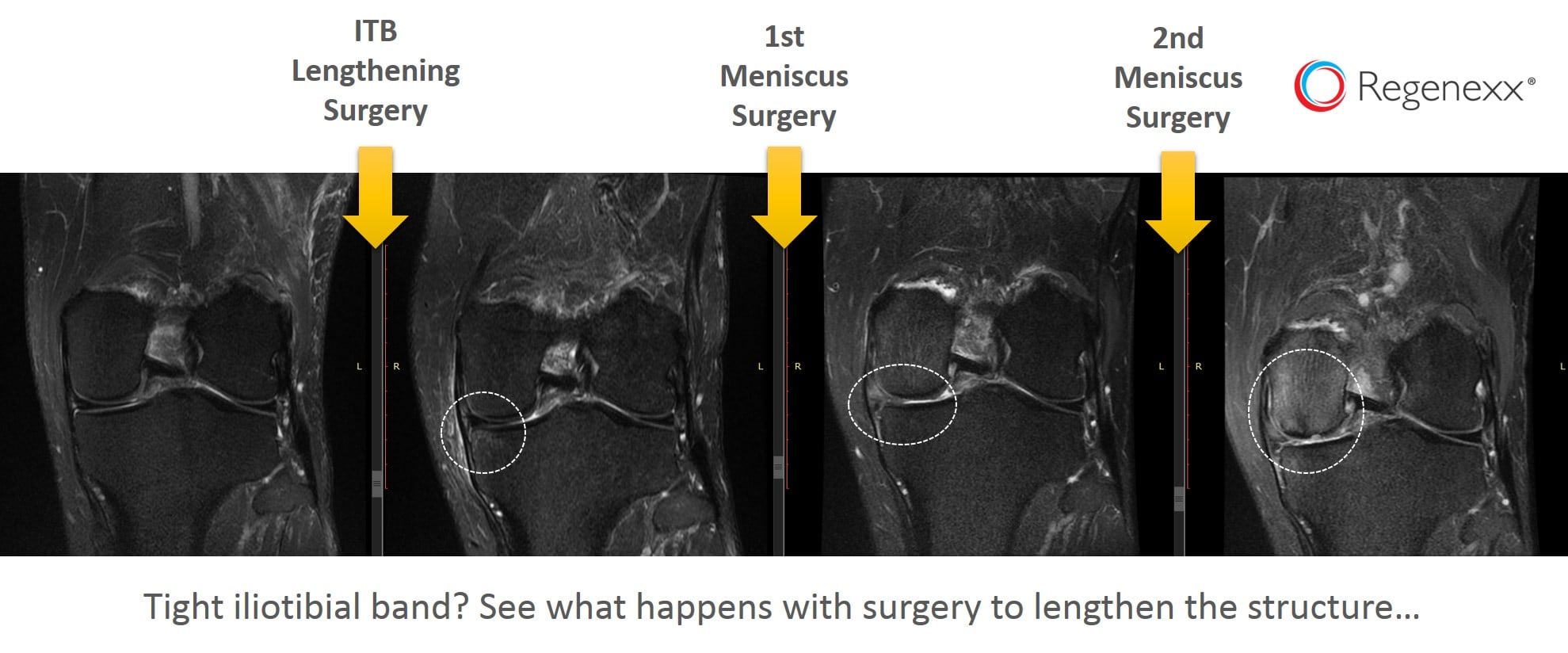

His images are above and arranged from earliest to latest. As you can see, his first MRI didn’t have any issues, which is what lead to the release surgery. Then a few months later, a meniscus tear shows up with some swelling in the bone (dashed white line and whitish color in the otherwise dark bone). He then underwent a partial meniscectomy surgery, one of the most common elective surgeries in the U.S. today. His knee got a bit better for a while, but then he re-tore the meniscus and had his second surgery. By that time, almost a year later, the cartilage on that side of the knee is beginning to erode. This is the lack of grey cartilage in the white dashed circle and the femur bone swelling (becoming whiter in color) in the third image. A second surgery was then performed, taking out even more meniscus. This lead to his current state and the MRI image on the far right, where his medial compartment cartilage is toast. At that point, he was offered a partial knee replacement, but he chose a Regenexx stem cell procedure instead.

Where ITB Release Surgery Falls Apart

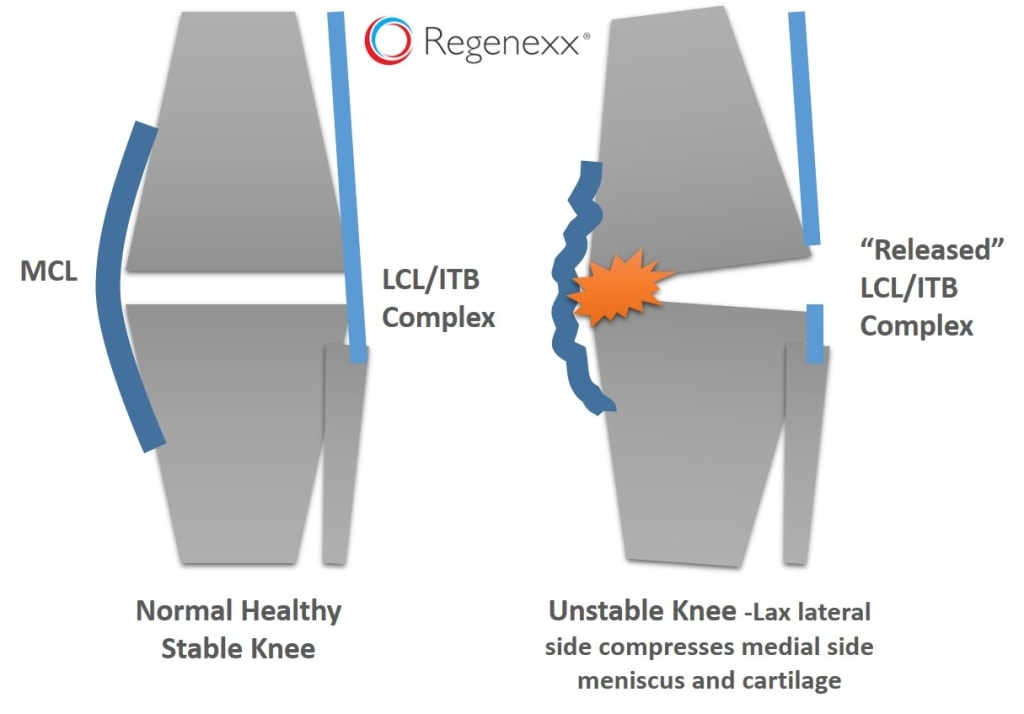

So why did an otherwise healthy runner’s knee go from almost perfect to totally destroyed in 24 months? The ITB release surgery. Check out the diagram below and read on…

The normal healthy knee on the left has tight “duct tape” on the sides that are there to keep each side of the knee stable with activity. The knee on the right after the surgical release of the ITB (which blends in with the lateral collateral ligament) has had the outside of the joint destabilized. Now that duct tape isn’t intact, or as tight. This allows the outside of the joint to open, which causes the inside (medial) to compress. This is why our runner’s medial meniscus was damaged and his cartilage was eventually chewed up. All of this was confirmed with a stress ultrasound exam, which shows that the outside of the knee is now horribly unstable.

The upshot? What seems like a simple surgical solution to a chronically tight ITB has wrecked this runner’s knee. Why? the body is tuned to micro-millimeter precision and disturbing that balance by cutting tight ligaments and tendons is a bad idea. In this case, his ITB tightness went away but resulted in an unstable and overloaded knee. Chances are good that his orthopedic surgeon lacked the biomechanical insight to link these two things (cutting his ITB and frying his medial knee compartment) and considered the procedure a resounding success! There are countless ways to treat a tight ITB and it’s important to be aware that it’s often caused by irritated nerves in the back or pelvic instability. Platelet rich plasma and other interventional and non-surgical techniques can now help heal this problem, so consider regenerative alternatives before signing up for this surgery!

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.