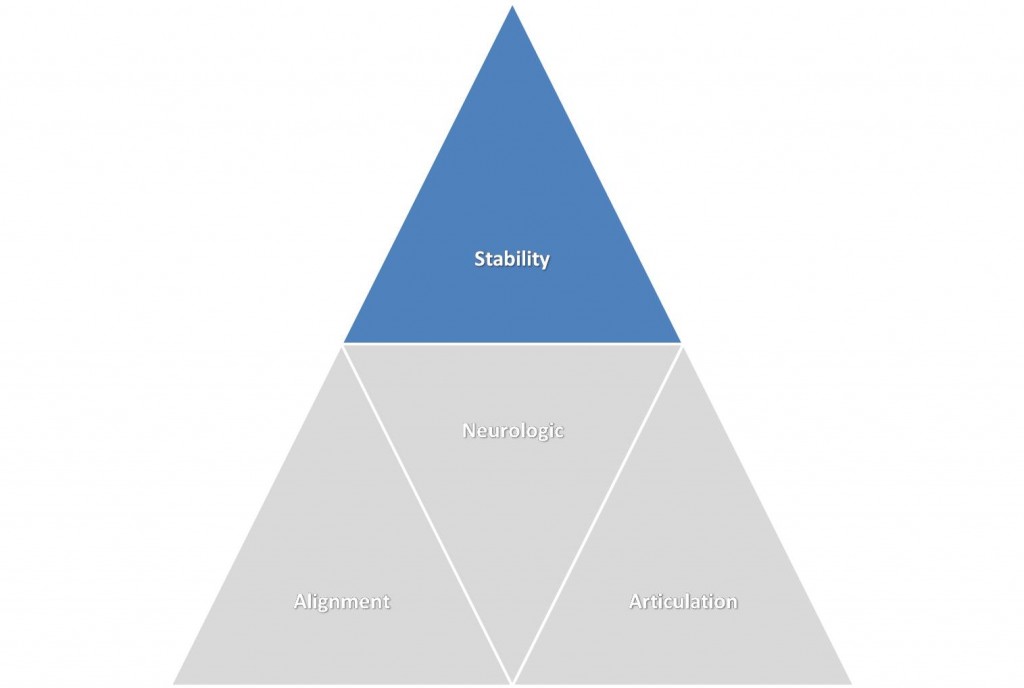

Orthopedics 2.0-Stability

Stability

What does it mean to be stable? Stable in a mechanical sense means resistance to falling part or falling down. Stable in terms of a joint means that the surfaces of the joint are kept in good alignment as we move. Why is this important? When the joint surfaces crash into one another and can’t be kept in good alignment while we move, the joint wears down much faster. It literally experiences many times the wear and tear of a stable joint. Since stability in many joints is the number one determinant of whether that joint will have a long happy life or be miserable very quickly and become “old” before it’s time, it’s a wonder more time isn’t spent accessing this component of joint health.

Let’s define joint stability a little further. Most of what’s been accessed with regard to joint stability is called “surgical stability”. This means that if a joint (either a joint like the knee or those in the spine) is very, very unstable and unable to hold itself together at all, surgery might be needed to stabilize the joint. Examples would be a completely torn ACL in the knee or severely damaged ligaments in the spine where a spinal cord injury is feared if the spine isn’t immediately stabilized. The knee may need a new cadaver or artificial ACL ligament implanted through surgery, while the spine may need a fusion where the spine bones (vertebra) are fused together with additional bone. These types of instability are rare. The more common type of instability is where small extra motions occur in the joint beyond the normal range, but not enough to warrant surgery. This type of instability has been called “sub-failure” instability, since it doesn’t involve the joint falling apart. This is the focus of this section, a discussion of what causes sub-failure instability and how it might be helped and why it’s so important when one considers joint repair or salvage rather than replacement. Our understanding of subfalure instability is younger and more immature, as more sophisticated instruments and tests have been needed to identify this type of instability. However, this type of instability is quite real and it’s a long-term insidious drag on joint health.

Sub-failure Stability 101

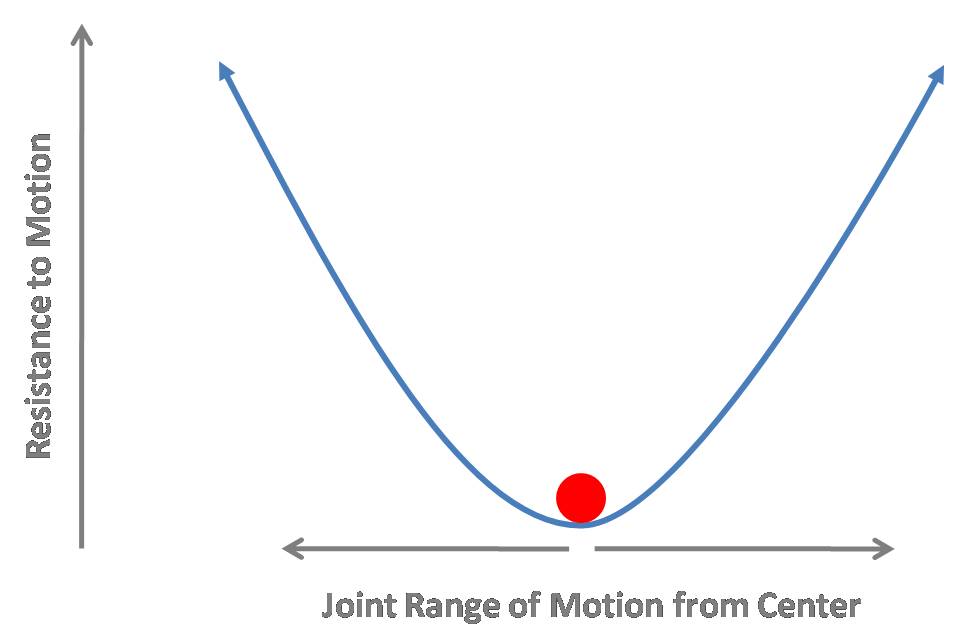

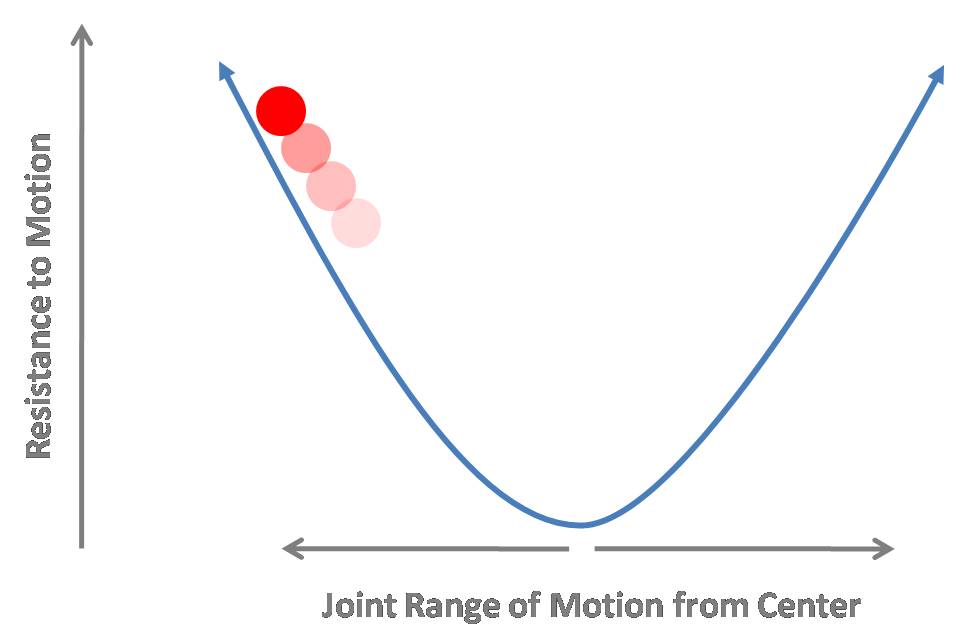

There are two types of sub-faulire instability. The first is muscular stability or what’s been called neuro-muscular stability. One of my favorite authors on stability, Panjabi has a great diagram that sums up normal stability of any joint. Consider the diagram below, the red ball in a blue cup. It represents what happens when you move any joint. Let’s start with your finger. Move it back and forth right now. As you move it only a little bit in a back and forth motion, there isn’t much resistance to motion. If you move it allot (bend it all the way back), there’s more resistance to motion. In fact, it eventually stops. This is because the ligaments that surround the joint (along with the covering of the joint, called the joint capsule), prevent motion and ultimately stop the joint from moving. In the picture below, the ball represents the amount of joint movement from the center. Like any ball in a cup, the ball naturally wants to stay at the bottom.

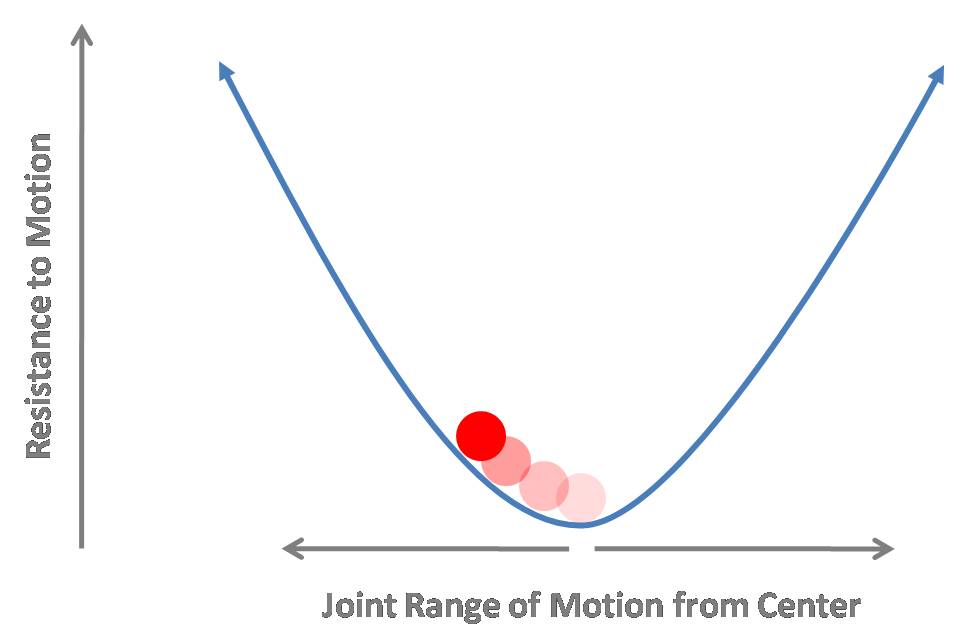

In the new diagrams below, we see what happens to the ball in two conditions. One is where the ball is kept in the middle of the cup. In this case, small forces act on the joint to keep the ball in the center of the cup. This is what our muscles do. They act as constant stabilizers for the joint, keeping it in good alignment while we move. Note that as the resistance of gravity tends to keep the ball in the middle of the cup, just as our muscles keep our joint in good position. This area is called the “neutral zone”, or the place in the joint range of motion in the middle where the muscles constantly act to keep the joint aligned properly. This is the middle of the range of motion of the joint.

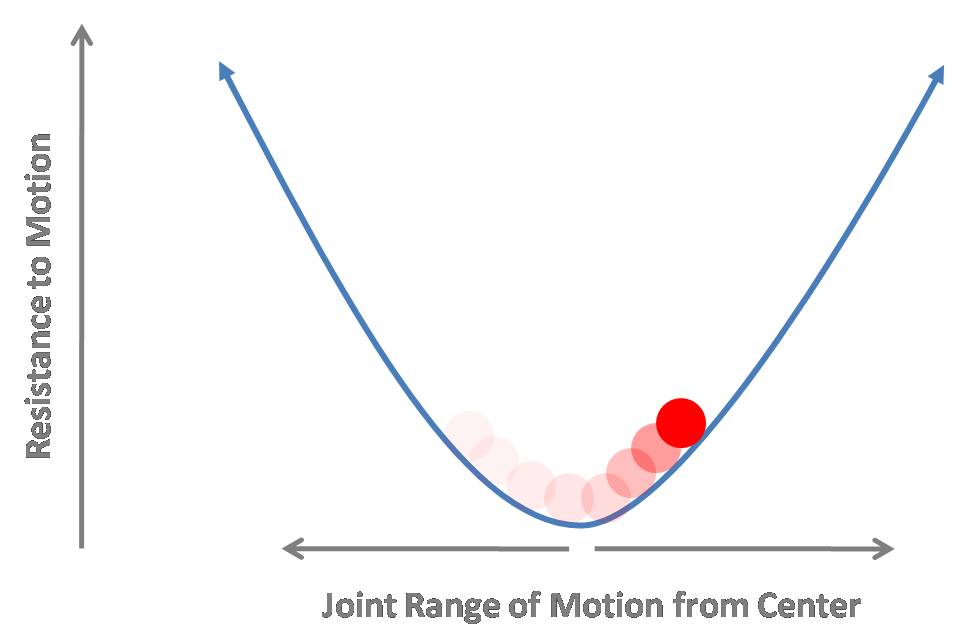

Now consider what happens as you bend your finger back again. The resistance goes dramatically up (it gets harder to bend the finger back) as you bend it way back. This is what happens as the ball ascends the wall of the cup, the resistance to continued motion gets more. This resistance to motion happens because the ligaments kick in to keep the joint aligned. The diagrams below show what happens to the ball, again in this circumstance, as it gets harder for the ball to climb the sides of the cup. In these instances, the ligaments act as the joint comes out of the neutral zone to protect the joint. They are in many respects the last line of defense against catastrophic failure of the joint.

So in summary, understanding stability is a bit like a ball in a cup. Our muscles provide constant input to the joint to keep the joint aligned as we move (the ball in the bottom of the cup or the joint in the neutral zone). When the joint goes too far in movement, the ligaments act as the last defense to prevent the joint moving too far and damaging the inside of the joint (the ball finding it harder to scale the sides of the cup).

Originally published on

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.