Understanding Medical Risk: Where Patients Go Wrong

I’ve blogged on this a few times, but when it comes to where patients often go wrong with keeping themselves safe, understanding medical risk is usually where they have a hard time. Hence, today we’ll go over several common medical risk scenarios to help you better decide how to manage your risk and live your life. Let’s dig in.

Risk is Everywhere

Whether it’s walking down the street or deciding on which medical procedure is best, deciding how best to access risk is critical to staying alive and healthy. It’s when that risk assessment gets out of whack that people develop problems living their best life. Why? This causes bad decisions to get made that lead to bad outcomes.

Today we’ll focus on places where I observe patients making irrational or the wrong medical risk decisions:

- COVID-19

- Spine Surgery

- Inverting the Ladder of Invasiveness

Many times these bad decisions get made because the information out there is slanted or the medical care system provides too little risk information. Hence, it’s the people who do their homework at a deep level rather than trusting the first thing they hear that often avoid these risks.

COVID-19

At this point, it’s becoming clear to physicians that we all made bad decisions during the pandemic. Some of those poor decisions were due to a lack of information, and some weren’t.

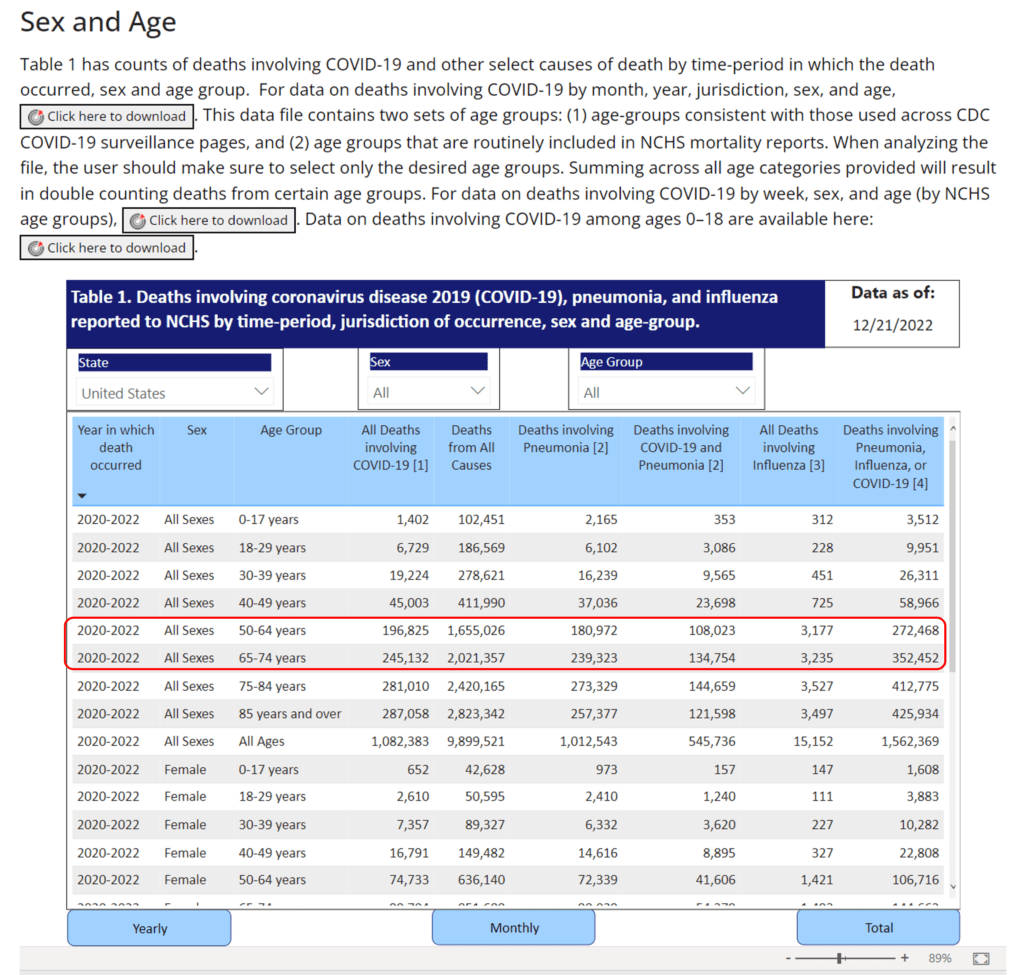

So how does a medical doctor view COVID-19 risk rationally at the end of 2022? I went to the CDC website and pulled up this information on deaths by age group, as age has always been the single biggest predictor of COVID risk:

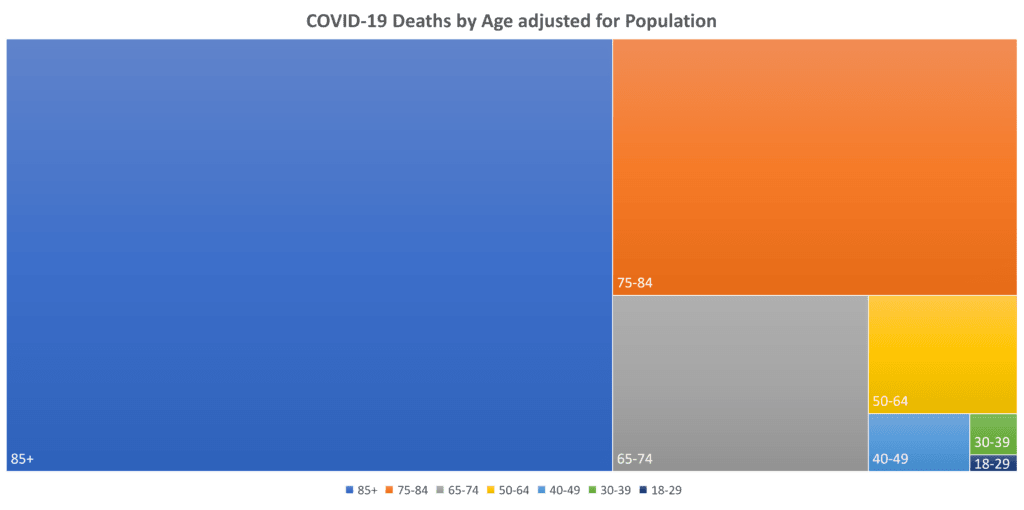

Wow, at first glance, this looks like there are lots of people aged 50-74 years old who are perishing. Not so fast because that’s the baby boom generation, so there are MANY more people at that age than in any other age group in the US. Once I manually adjusted for the population size, this is your actual risk by age group of dying from COVID-19. To understand how clinics like Regenexx have created COVID-safe zones to mitigate that risk, see this example from their Tampa Bay location.

So as you can see, the baby boomers aged 50-74 make up only a tiny fraction of the deaths in older age groups. The aged 75 and up crowd makes up the vast majority of deaths. Hence, as a 59-year-old, the serious health impact of COVID-19 on someone my age is minimal.

How about Long-COVID, as the information on this shows that it’s a plague-like epidemic? The problem is that all we’ve had to date are observational point-in-time studies. That means that researchers have looked at a specific patient population and showed that the patient who reported having COVID had a set of complaints. However, we have no idea if COVID caused those symptoms. This past month we finally had our first cross-sectional studies that compared COVID+ and COVID- people over time to see what symptoms or problems each developed. Both studies showed that patients who were COVID+ were no more likely to develop the symptoms of what has been called Long-COVID than COVID- patients (2,3). Hence, the data to date shows that long-COVID is more a product of the pandemic than an actual disease we should all be concerned about.

Conclusions? I’m not concerned about COVID-19 as in the pantheon of risks a 59-year-old faces, like diabetes, heart disease, and cancer, COVID is no longer in that category. So I’ll mask when told to and keep washing my hands, but I won’t allow the fear of catching COVID-19 to impact living my life.

Spine Surgical Risks

To illustrate this one, let me discuss a patient I treated this week. This elderly woman is miserable after a C2-C4 fusion. She hasn’t slept in a month because that fusion is causing overload at the level above at C1-C2, and the surgeons fused her into a backward neck curve. Did she need that fusion?

This patient had a very tight central canal at C2-C4 that was irritating the spinal cord. She also had swollen ligaments in the back of the spinal canal, making this worse. From a surgical standpoint, the usual move in 2022 is to decompress the area surgically by removing parts of the disc, bone, and swollen ligament and then bolting the bones together with a fusion. First, let’s see if adding the fusion, which is now causing so many disabling problems, was needed or just the decompression would have sufficed. Several studies show that fusion with decompression produces the same results as decompression alone (4-6). That means that this patient could have just been surgically decompressed and that this surgery would not have resulted in her current serious overload problem at C1-C2, as the lower C2-C4 levels would have still moved.

The problem here is a classic one; the patient listened to what the surgeon recommended. She likely never realized that the hardcore research in this area had confirmed many times that adding the fusion only adds complications without adding benefits.

Inverting the Ladder of Invasiveness

One of the hardest concepts for patients to grasp is that to stay safe in today’s medical system, you must always go with the least invasive procedure that may help. I call this the ladder of invasiveness. The problem here is that patients mix this up by not understanding medical risk and often choose procedures that are far too invasive. Let me explain with a common one I hear every day.

A good chunk of my practice is seeing patients with cranial-cervical instability. Many of these patients will get diagnosed with the rather shaky diagnosis of occult tethered cord. This means that the spinal cord isn’t free to move and that this is causing symptoms. Never mind that making this diagnosis is more judgment call than science, the solution often recommended to them is to cut the filum terminale, a piece of connective tissue that anchors the spinal cord in the sacrum. This is called a “tethered cord release.” Let’s look at the risks of that procedure.

Here are the common tethered cord release complications:

- 4.7-7% risk of serious infection in the spinal cord area (7,9)

- A 4.5-18.6%% chance of spinal fluid leak (8,9)

Despite these complications, many of these patients put a tethered cord release before far less invasive specialized injections to treat their CCI that, to date, have had none of these associated complications. That’s a dangerous inversion of the ladder of invasiveness. You should instead put the lower-risk treatment first (injections), and only if the symptoms associated with tethered cord persist, then choose surgery.

The upshot? Understanding medical risk can help you make good medical decisions. Sometimes it does take some digging to figure out the actual risks you’re facing.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

References:

(2) Pinto Pereira SM, Shafran R, Nugawela MD, Panagi L, Hargreaves D, Ladhani SN, Bennett SD, Chalder T, Dalrymple E, Ford T, Heyman I, McOwat K, Rojas NK, Sharma K, Simmons R, White SR, Stephenson T. Natural course of health and well-being in non-hospitalised children and young people after testing for SARS-CoV-2: A prospective follow-up study over 12 months. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022 Dec 5:100554. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100554. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36504922; PMCID: PMC9719829.

(3) Subramanian, A., Nirantharakumar, K., Hughes, S. et al. Symptoms and risk factors for long COVID in non-hospitalized adults. Nat Med 28, 1706–1714 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01909-w

(4) Dijkerman ML, Overdevest GM, Moojen WA, Vleggeert-Lankamp CLA. Decompression with or without concomitant fusion in lumbar stenosis due to degenerative spondylolisthesis: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2018 Jul;27(7):1629-1643. doi: 10.1007/s00586-017-5436-5. Epub 2018 Feb 5. PMID: 29404693

(5) Machado GC, Ferreira PH, Harris IA, Pinheiro MB, Koes BW, van Tulder M, Rzewuska M, Maher CG, Ferreira ML. Effectiveness of surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015 Mar 30;10(3):e0122800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122800. PMID: 25822730; PMCID: PMC4378944.

(6) Chen B, Lv Y, Wang ZC, Guo XC, Chao CZ. Decompression with fusion versus decompression in the treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020 Sep 18;99(38):e21973. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000021973. PMID: 32957316; PMCID: PMC7505294.

(7) Alexiades NG, Shao B, Ahn ES, Blount JP, Brockmeyer DL, Hankinson TC, Nesvick CL, Sandberg DI, Heuer GG, Saiman L, Feldstein NA, Anderson RCE. High prevalence of gram-negative and multiorganism surgical site infections after pediatric complex tethered spinal cord surgery: a multicenter study. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2022 Jul 22:1-7. doi: 10.3171/2022.6.PEDS2238. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35901675.

(8) Baldia M, Rajshekhar V. Minimizing CSF Leak and Wound Complications in Tethered Cord Surgery with Prone Positioning: Outcomes in 350 Patients. World Neurosurg. 2020 May;137:e610-e617. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.02.073. Epub 2020 Feb 20. PMID: 32088374.

(9) Elmesallamy, W., AbdAlwanis, A. & Mohamed, S. Tethered cord syndrome: surgical outcome of 43 cases and review of literatures. Egypt J Neurosurg 34, 4 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41984-019-0029-8

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.