What You Need to Know Before Signing Up for Spinal Decompression

Much of modern back surgery is about solving one problem and then creating two others. Spinal decompression is no different. So let’s dive into this topic.

Spinal Decompression Addresses One Problem but Creates Another

Spinal decompression (aka laminectomy) damages local stabilizing muscles, so it is yet another procedure that in most cases I would label as surgery that is damage to accomplish a goal. Why? Because it fixes one problem by creating another. Let me explain.

Spinal decompression is most commonly performed for spinal stenosis, because the space the nerves travel through in the spinal canal has narrowed. The purpose of a decompressive laminectomy is to open up this space in the spine by excising some bone to eliminate pressure on the nerves. In the process, the surgery also removes stabilizing structures that attach to the bone as well as part of the facet joint, creating instability in the spine. In order to attempt to stabilize itself, the body will form more bone spurs in that area, potentially creating even more problems.

So as you can see, spinal decompression is a problem all in itself; however, add in a spinal fusion, as is often done, and it could make the situation even worse. More concerning is that the research shows that adding in the fusion doesn’t help. Before we get there, let’s dive deeper into some of the terms the surgeon or hospital likely used when explaining these spine procedures.

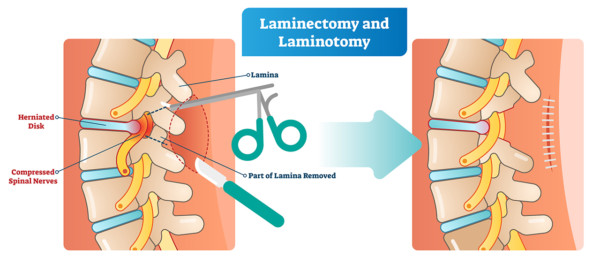

What Does Laminectomy Mean?

VectorMine/Shutterstock

The lamina is the roof of the spinal canal. Think of the canal (the place where your spinal cord and nerves travel up and down in the spine) as a house. The bony roof of the house that contains your spinal cord and nerves is called the lamina. The ceiling under the roof is the yellow ligament called the ligamentum flavum. The windows on either side of the house are called the foramina (each is called a foramen). The walls are the facet joints on either side. The floor of that house is where the vertebrae and discs live.

A laminectomy, therefore, is a surgery to unroof the house to open more space because the ceiling (ligamentum flavum) has grown too big and the walls (the facet joints) have also become too big. In addition, the discs and vertebrae can also put pressure from the bottom up (disc bulge or bone spur). A foraminotomy is a procedure to open the windows when they become closed due to bony overgrowth (usually by thickening of the walls, called facet hypertrophy or arthritic facet joints).

Spinal Fusion No Better Than Spinal Decompression Alone

If you do decide to sign on the dotted line for spinal decompression, something you should only consider as a very last resort, at the very least, make sure spinal fusion is not part of the procedure. Over the last couple of decades, in an effort to minimize movement in the operated area of the spine, surgeons started adding back fusions in conjunction with these laminectomies. Studies have shown that in addition to increasing complications following surgery, outcomes with fusion are no better than with spinal decompression alone. In addition, laminectomy for spinal stenosis, for example, has been found to be 60–90% safer when performed without a fusion.

More Reasons to Avoid Back Fusion

If spinal decompression is a bad idea, a back fusion (with or without laminectomy) is often a dumb one. With a back fusion two or more backbones, or vertebrae, are “locked” together using hardware and screws to encourage the bones to fuse into a solid mass. Back fusion is most commonly performed for spinal stenosis, which occurs due to arthritis creating pressure on nerves, degenerative disc disease, or other spinal conditions that result in pain or functional issues.

Fusions are highly invasive and risky, and recovery is lengthy. Outcomes, unfortunately, aren’t good and can even be quite debilitating as the areas of the spine above and below the now fused spine (adjacent segments) become overloaded, attempting to compensate with extra motion. This causes more pain, degeneration, bone spurs, and arthritis, and, in many cases, more fusions in the future. This condition is so common it has a name: adjacent segment disease (ASD).

Learn more about adjacent segment disease by watching my video below:

Additionally, even as far out as two to five years following spinal fusion, the surgery has been shown to not improve patient outcomes any more than a spinal decompression alone. Even if one is willing to risk the ASD, spinal fusion just doesn’t seem to be helping patients. In other words, you’re risking further damage with ASD, and the goal of the fusion isn’t even being realized.

How About Replacing My Disc?

A newer idea is disc replacement. This means that rather than fusing the spine, the degenerated disc is removed and a prosthetic disc is put in its place. The idea is that this is supposed to allow for more normal motion and avoid ASD. The problem? This doesn’t really work as advertised, as recent studies have shown that you still get adjacent segment disease with a disc replacement and that the rates of breakdown are similar to if you had a fusion.

Can All of This Be Treated Without Surgery?

It’s important to note that there are nonsurgical interventional orthopedics solutions for spinal stenosis, arthritis, and other spine conditions. However, if you are still considering going the surgical route with a spinal decompression, please don’t agree to a fusion in the process. See my video below to learn how all of this can be treated nonsurgically:

The upshot? Again, most spine surgery solves one problem and creates two more. Spinal decompression surgery is no different. So please first look at newer nonsurgical options that involve placing your own platelets or stem cells into precise spots to open up these areas through ligament tightening without the surgical bull-in-the-china-shop approach!

Originally published on

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.