Can You Have Serious Neck Injuries and a “Normal” MRI?

MRI has been a game-changing technology in medicine. However, as I have blogged many times, our overreliance on MRI reports as physicians who treat patients in pain isn’t a net positive. So today we’ll go over a concept that’s not new, that serious traumatic neck injuries may not be detected on MRI. Let’s dive in.

Talor and Twomey

If a doctor wants to become a real expert in treating neck pain, a few names are required reading. One was a Yale-based professor named Monohar Panjabi, Ph.D. Another required reading for doctors who treat patients with chronic neck pain is a series of articles published by James Taylor and Lance Twomey from western Australia.

James was training to be a surgeon when his career steered toward academic anatomy. As he recounts it, that switch happened after needing to be rescued from medical missionary work in the Belgian Congo in the 60s. His first Ph.D. student was Lance Twomey who was a physical therapist. The team eventually developed new methods of sectioning frozen autopsy specimens that began to reveal all sorts of neck injuries that had been missed.

These two published a series of spine publications in the 90s that very much shaped a critical core belief of mine. What’s that? Serious neck injuries that evade the detection of even our most powerful MRI machines are probably more common than we’re willing to admit. Let’s review their research and the contents of their seminal book, “The Cervical Spine”.

A Book Appears

My wife yesterday was trying to find some permanent markers in my office and was digging through a bookshelf and this book by Taylor and Twomey, “The Cervical Spine” appeared. I hadn’t seen it in years, but leafing through the pages at the amazing one-of-a-kind images, I knew that this topic needed a blog. This text was put together after the team published a series of seminal papers on obvious occult neck injuries in patients who had died of blunt trauma (1-4).

The amazing cross-section slides they prepared and that are featured in the book all were of patients who had died of blunt trauma. What’s that? That’s when someone dies of something like a burst spleen in a car crash. These autopsies had identified the cause of death, but according to the pathologist, they had no obvious neck injuries. Many of these neck injuries would never have been detected even with our more powerful 3T MRIs of today.

Some Examples

First, this book is hard to get, which means that these days you can’t find it on Amazon. So my purpose of sharing a few images from the book of hundreds of amazing images is editorial in nature and to get you to purchase your own copy.

Now let’s review the obvious occult neck injuries identified by Taylor and Twomey.

Dorsal Root Ganglion Injury

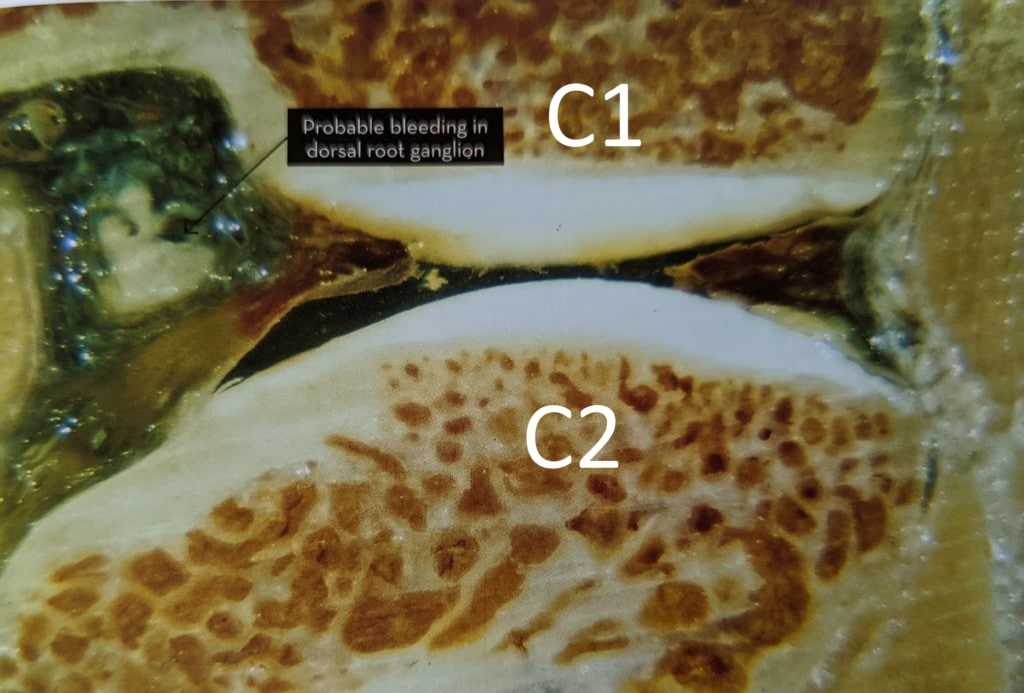

Credit: James Taylor, Elsevier-ISBN: 9780729542715

This is a cross-section through the C1-C2 facet joint. You can see the red/white bone and then white cartilage just below the “C1” and above the “C2”. Behind that joint lives the C2 dorsal root ganglion which is the part of the spinal nerve that carries pain signals. In this cross-section, you can see bleeding in that C2 DRG.

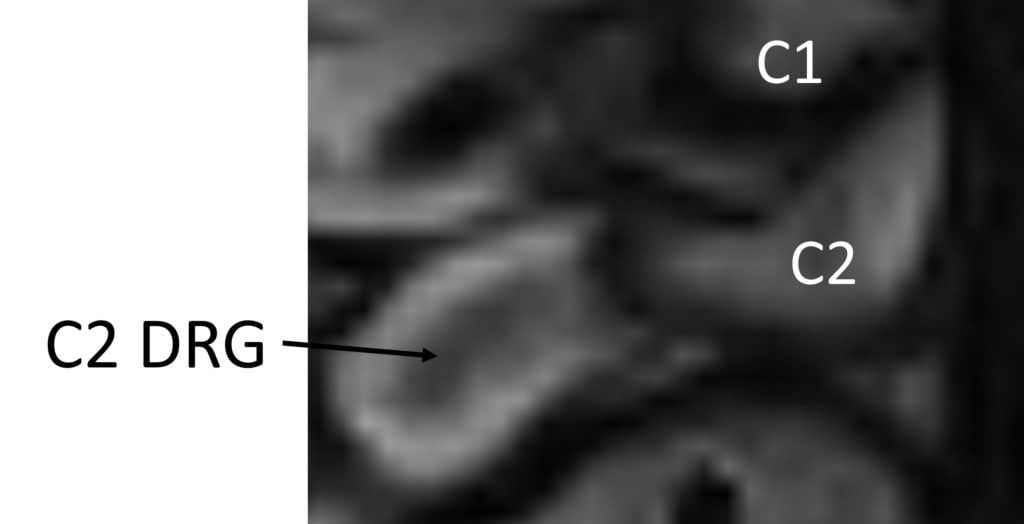

This is what this area looks like on a standard 1.5T MRI of today. That little pixelated smudge is the C2 DRG. We got lucky on this patient as the DRG is bigger and likely was caught making a turn, so we see more of it. The problem is that there is no way on God’s green earth that any reading radiologist would be able to pick up what you clearly see in the Taylor and Twomey book image above on this neck MRI. That’s despite the fact that this injury could cause chronic permanent headache pain. Why? This nerve supplies sensation to the head. So how many patients have damaged their C2 DRGs in car crashes or other traumatic injuries and these injuries went undetected on MRI?

Maybe this kind of injury is uncommon? Nope, Taylor and Twomey identified 109 of these injuries. That was 14% of all patients who died of blunt trauma and 35% of those patients who survived from hours to days (4).

Disc Injuries

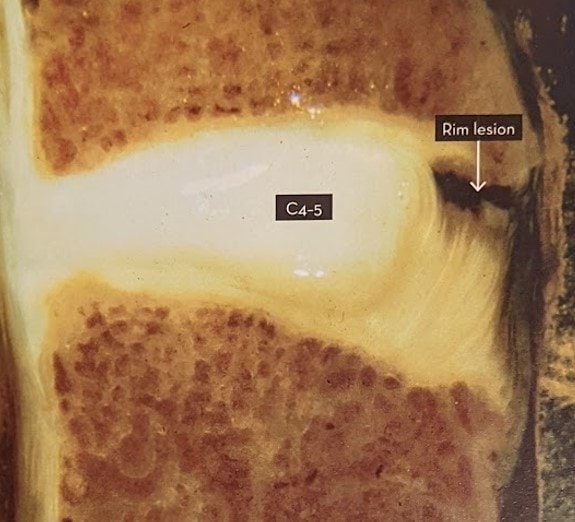

Above we see a cross-section through the neck of a 20-year-old woman who again died of blunt trauma. There was no neck injury reported on the autopsy report, but here we see a serious injury in the front of the C4-C5 disc called a “rim lesion”. That’s where the fibrous part of the disc called the annulus has pulled away from the bone of the vertebra. Taylor and Twomey also published a series of identified disc injuries (2).

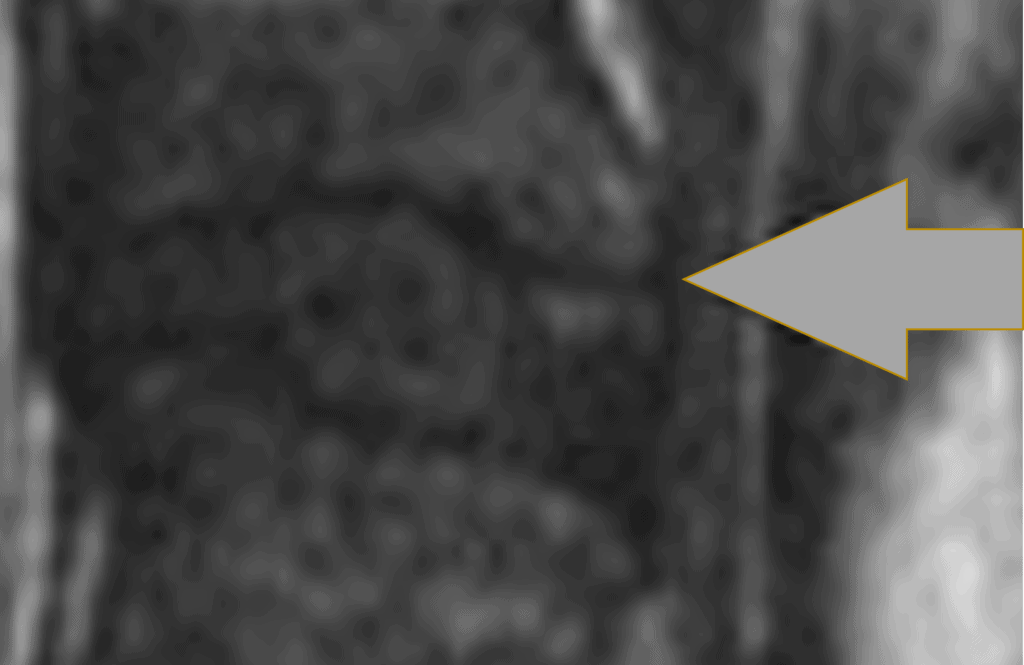

Above we see a standard 1.5T MRI with the grey arrow pointing to a disc rim injury, which is that little brighter line in the top part of the disc. Despite this being a serious injury that also usually involves injury to the Anterior Longitudinal Ligament in the front of the neck, this finding is unlikely to make it into an MRI report. That’s despite this injury possibly causing the C4 vertebra to move backward on the C5 in neck extension (retrolisthesis). If this was noticed by the reading radiologist it would usually be called pre-existing degenerative disc disease.

Facet Joint Injuries

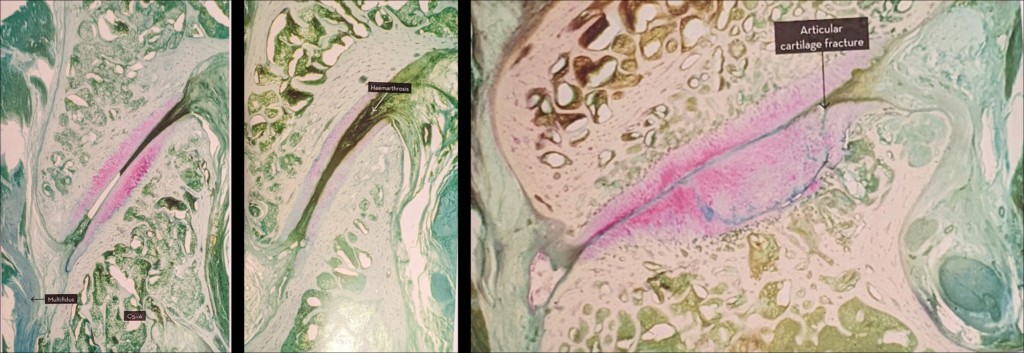

The neck facet joints are finger-sized articulations that are present at every spinal level in the neck. Injuries to these structures can cause chronic pain and are treated in different ways including steroid injections and radiofrequency ablation (5). Above we see three different facet joint injury cases from Taylor and Twomey. On the left is bleeding into the joint, in the middle is a joint filled with blood, and on the right is cartilage and bone injury.

Above is the current state-of-the-art MRI of the facet joint. This is a very good and “lucky” image as the sagittal slices happen to catch the joint perfectly as we see it in the Talor/Twomey images, which doesn’t always happen. Despite this being a very good MRI image of this small joint, any reasonable person can see that it’s a “smudge-o-gram”. Meaning it’s a fuzzy and badly pixelated representation of what’s really there.

If this joint were filled with blood would it be noticed? Nope. If anything that would likely be read out as a small joint effusion (swelling) indicative of early degenerative disease and not related to a neck injury. Also, note that the cartilage in this MRI image is barely visible as a single grey line. So an injury to that cartilage would at most show up as a pixelated spec that would be ignored.

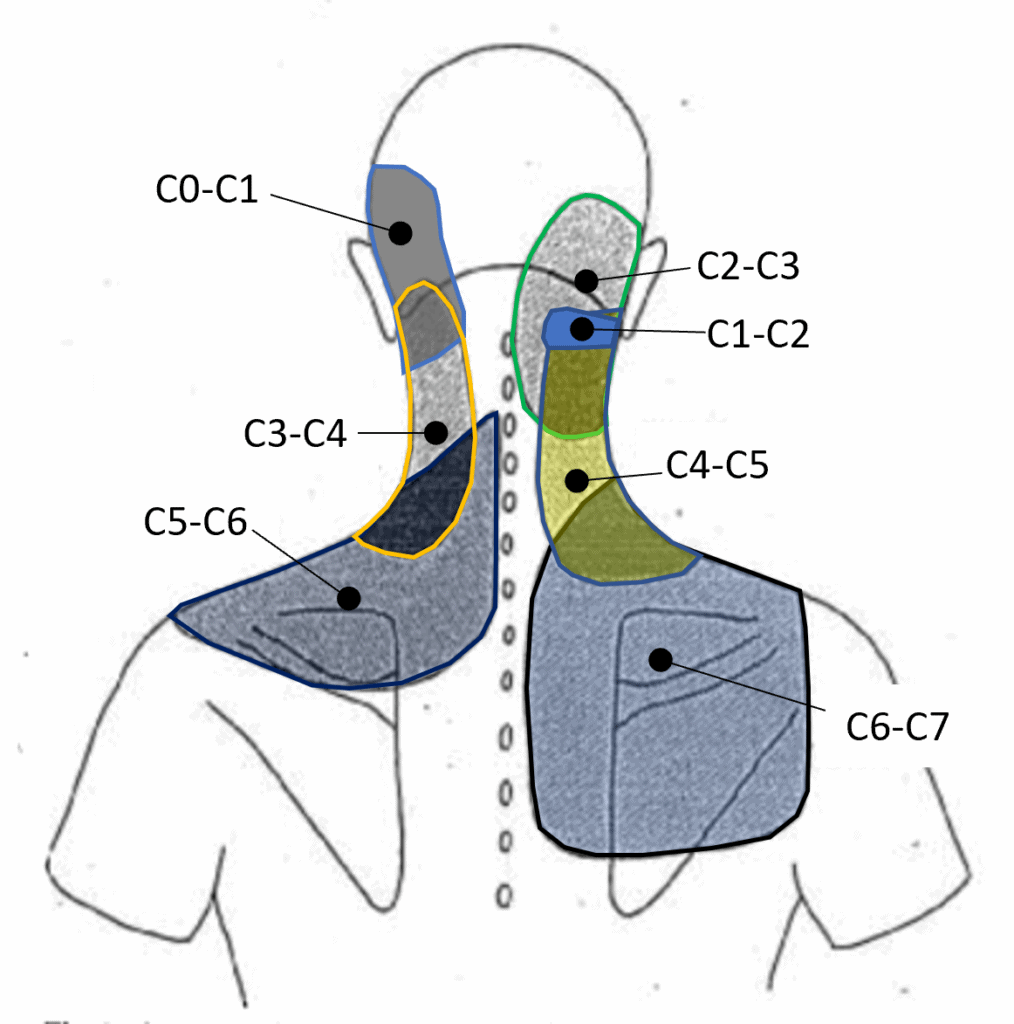

Here’s a map of where these facet joint injuries can refer chronic pain (6):

Credit: Heavily modified image taken from Dwyer et al

As you can see, permanent pain everywhere from the head to the neck to the upper back can come from these facet joint injuries that we really can’t “see” with today’s MRI technology.

Summary

I hope you see the frustrations of a physician who treats patients with chronic neck injuries. The MRI technology available to us really doesn’t have the ability to detect injuries to these small, but critical structures that when injured, can cause a lifetime of chronic neck, head, or upper back pain. If anything, these structures show up as a pixelated smudge on closed bore 1.5T or 3.0T MRI. The quality of those images is even worse on lower field upright MRI imaging.

Is there any hope of getting a diagnosis and help? Yes, that’s why a good hands-on physical exam where the doctor examines every single facet joint through palpation is key. In addition, these days adding motion to imaging may identify the downstream consequences of these injuries. For example, instability at C1-C2 as seen on DMX (7). Or a flexion-extension upright MRI that shows a retrolisthesis at C4 on C5 in extension indicating an injury to the ALL.

The upshot? As you can plainly see based on the excellent work of Taylor and Twomey in the nineties, we still don’t possess imaging technology good enough to identify many serious neck injuries. Given that this hasn’t changed in 30 years, it’s unlikely to get better anytime soon. Hence, that’s why there is no substitute for a good hands-on physical exam.

________________________________________________________

References:

(1) Taylor JR, Twomey LT. Acute injuries to cervical joints. An autopsy study of neck sprain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1993 Jul;18(9):1115-22. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199307000-00001. PMID: 8362316.

(2) Taylor JR, Twomey LT. Disc injuries in cervical trauma. Lancet. 1990 Nov 24;336(8726):1318. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)93001-6. PMID: 1978139.

(3) Schonstrom N, Twomey L, Taylor J. The lateral atlanto-axial joints and their synovial folds: an in vitro study of soft tissue injuries and fractures. J Trauma. 1993 Dec;35(6):886-92. PMID: 8263988.

(4) Taylor JR, Twomey LT, Kakulas BA. Dorsal root ganglion injuries in 109 blunt trauma fatalities. Injury. 1998 Jun;29(5):335-9. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(98)80027-2. PMID: 9813674.

(5) Bogduk N. On cervical zygapophysial joint pain after whiplash. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011 Dec 1;36(25 Suppl):S194-9. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182387f1d. PMID: 22020612.

(6) Dwyer A, Aprill C, Bogduk N. Cervical zygapophyseal joint pain patterns. I: A study in normal volunteers. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1990 Jun;15(6):453-7. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199006000-00004. PMID: 2402682.

(7) Freeman MD, Katz EA, Rosa SL, Gatterman BG, Strömmer EMF, Leith WM. Diagnostic Accuracy of Videofluoroscopy for Symptomatic Cervical Spine Injury Following Whiplash Trauma. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Mar 5;17(5):1693. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051693. PMID: 32150926; PMCID: PMC7084423.

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.