How to Interpret the Different Trajectories of Ligament Healing

Credit: Shutterstock

We can now help many ligament injuries heal through precise injections rather than surgery. Most patients do great, but some are left trying to read the tea leaves of their recovery pattern to see how this impacts their future. So let’s review most of the possible outcomes and learn from them.

My Ligament Healing History

I still remember a study I published almost 2 decades ago. I had successfully treated many chronic neck pain patients with fluoroscopy-guided prolotherapy injections. The idea was that their spinal instability caused by damaged ligaments could be easily measured on flexion-extension x-rays. The goal was to help those ligaments heal and improve that excessive motion. Hence, in the study, we used a blinded reader who didn’t know which set of x-rays was done before the treatments and which after. In the end, we demonstrated that cervical instability improved after these procedures (1). Meaning, this was the first published evidence that prolotherapy was capable of ligament healing in patients with chronic neck pain caused by trauma.

Ligament Healing 101

How do ligaments heal? The first thing that happens is an injury that brings bleeding which allows platelets and other cells into the area. This then causes swelling which artificially tightens the ligament. The platelets and stem cells in the area then do their jobs by excreting growth factors, cytokines, and exosomes to orchestrate healing. Local fibroblasts are then stimulated to produce new collagen (or the local progenitor (stem) cells turn into new fibroblasts). Think of this as the bricks and mortar that are initially laid down in a disorganized way. Over time, as the ligament is loaded, this disorganized collagen gets remodeled into strong dense fibers that all go the same direction.

Think of injection-assisted ligament healing as giving you another bite at the above-described healing cascade when the normal process didn’t get it done. Hence, we can use precise injections of prolotherapy, platelet-rich plasma, or things like your own bone marrow concentrate (that contains stem cells) to give your ligaments another shot at healing.

The Trajectories of Ligament Healing

The vast majority of patients do great with injections to assist their ligament healing. Hence they tend to be in the first three categories I’ll describe:

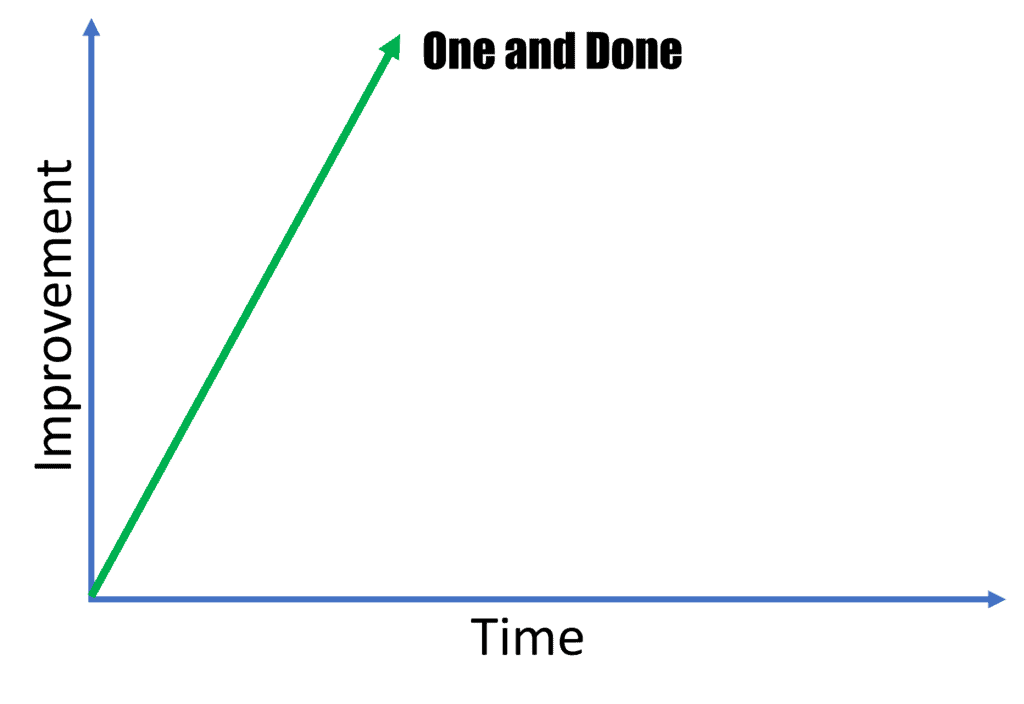

One and Done

These are patients who get better quickly after a single ligament injection. They usually have less severe ligament injuries and depending on the ligament injured they can make up a large or small proportion of the patients we treat. For example, most patients with a lower grade MCL ligament injury of the knee are one and done. On the other hand, fewer patients with chronic spinal injury are in this category.

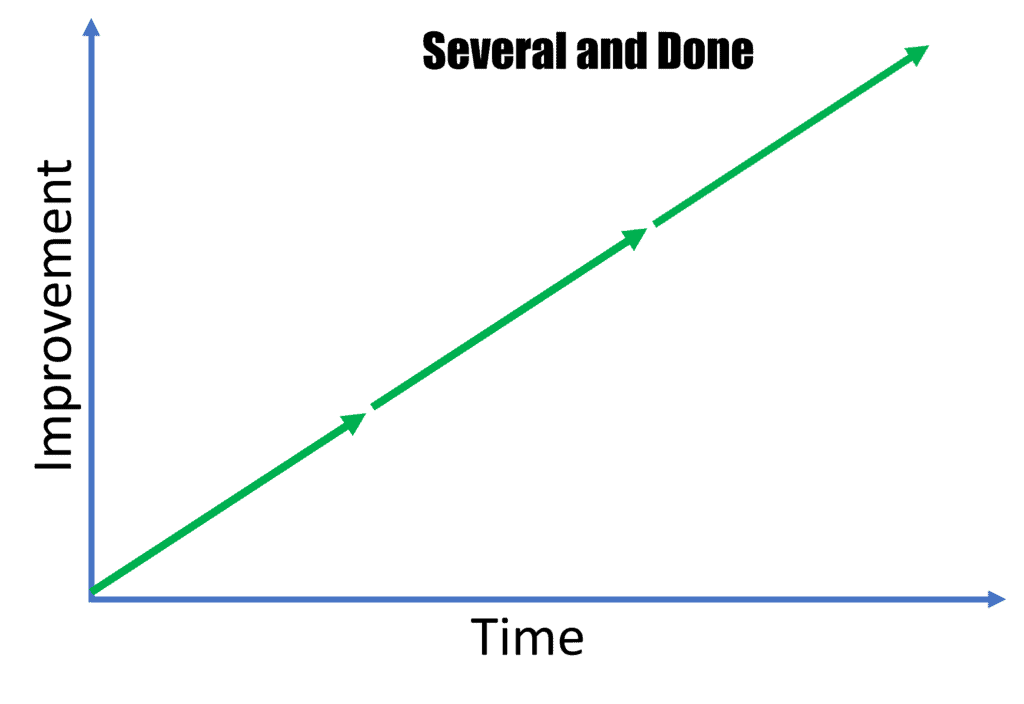

Several and Done

This is the category that most patients with chronic spinal instability find themselves. They get better with each injection and at some point, we reach a plateau of what can be done or they’re fully better and need no more care. This is usually accomplished through 2-4 rounds of treatment.

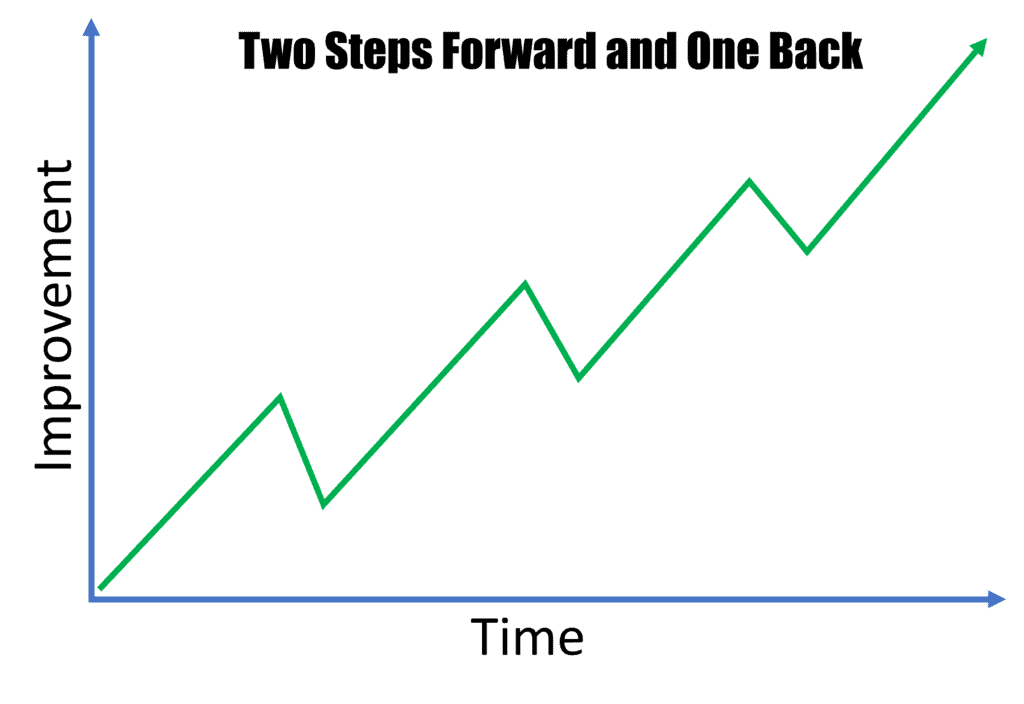

Two Steps Forward and One Back

This is also a common recovery scenario that we observe. Basically, the patient’s symptoms are better for weeks to months after the injection, but then they partially regress. However, they don’t regress all of the way back to their pre-injection symptoms, so they make overall progress. Basically, it’s two steps forward and one back.

Why is this happening? If the patient feels better for weeks, then this is due to the artificial stability provided by the swelling of the ligament in the acute healing phase.

If the progress lasts for months and then the patient regresses, it’s likely the difference between ligament hypertrophy and normal tight ligament bundles. When the body is trying to heal a ligament and can’t get it fully done, it just throws more disorganized collagen at the area, making the ligament bigger. The good news is that a bigger ligament is usually tighter, but it’s also weaker. During this phase of healing, there may be some relief that comes from the bigger ligament. However, ultimately the body aligns all of that new disorganized collagen into organized bundles that all head in the same direction. This creates a smaller and more dense ligament, but one that is no longer as tight as the hypertrophic one. The good news is that this denser ligament will have greater overall strength for the long run.

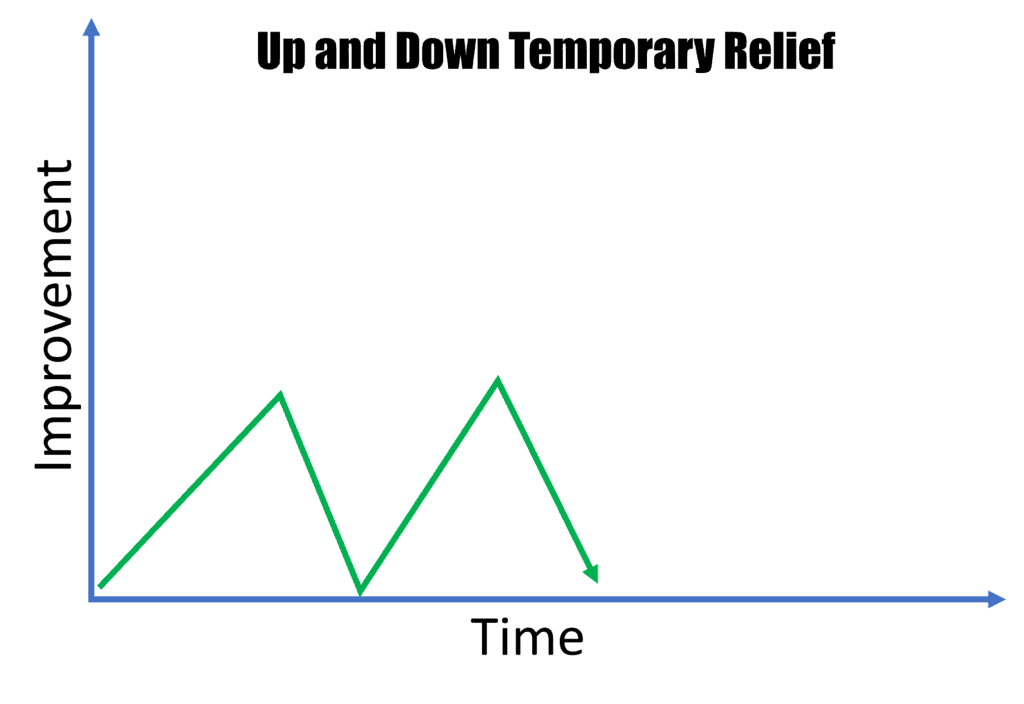

Up and Down Temporary Relief

Now we enter into recovery trajectories where action could be needed. The first is up and down relief. The patient gets better for a few months and then completely regresses backward to where they were prior to the procedure. In this case, the ligament injury is usually more severe. There are a few options here to get forward traction:

- More frequent treatment-If the ligament injury is big enough and the load on the area is large enough, then the progress toward healing over several months can be lost to continued wear and tear. Hence, in this case, more frequent treatment usually solves the issue. Meaning, if someone was getting treated every couple of months, moving them up to monthly or every 6-week treatment could be the answer.

- Reduce the load on the area-This is a tough one, as sometimes it can be done easily with bracing that allows activity, and sometimes it can’t be done. For example, a knee MCL that isn’t healing can be easily braced with activity by a device that takes the weight off the MCL, but still allows walking or even light jogging. However, you can’t do this with the neck or back, as your only option is to fully immobilize the spine, which causes muscle atrophy. Given that those muscles are required to stabilize and protect the ligaments, making them smaller and weaker through a brace is counterproductive. You can try to “thread the needle” and only use spine bracing when the patient is performing certain activities, which is usually the best move.

- Increase the punch of the therapy-You can also increase the healing power behind what’s injected. Hence, if the patient was first treated with prolotherapy, you can upgrade to PRP. If at a lower dose of PRP, you can increase the dose of platelets. If the patient fails with high-dose PRP, you can upgrade to bone marrow concentrate.

- Too much systemic inflammation-We know from lab and animal studies that too much chronic systemic inflammation (like many people with metabolic syndrome experience) can hurt ligament healing (2). One proposed solution is to add high-dose omega 3 fatty acids. For patients, this can be adding high-quality fish oil supplements or getting rid of the metabolic syndrome. That last part usually means shedding pounds and getting rid of the dietary habits that usually kill Americans like sugar, artificial fats, and processed food.

- Malnutrition-In Americans this is rarely the case, but we do know that nutrients like vitamins C and D, manganese, copper, and zinc are involved in healing, so taking a good multi-vitamin or getting these nutrients through a balanced whole food diet is a good idea.

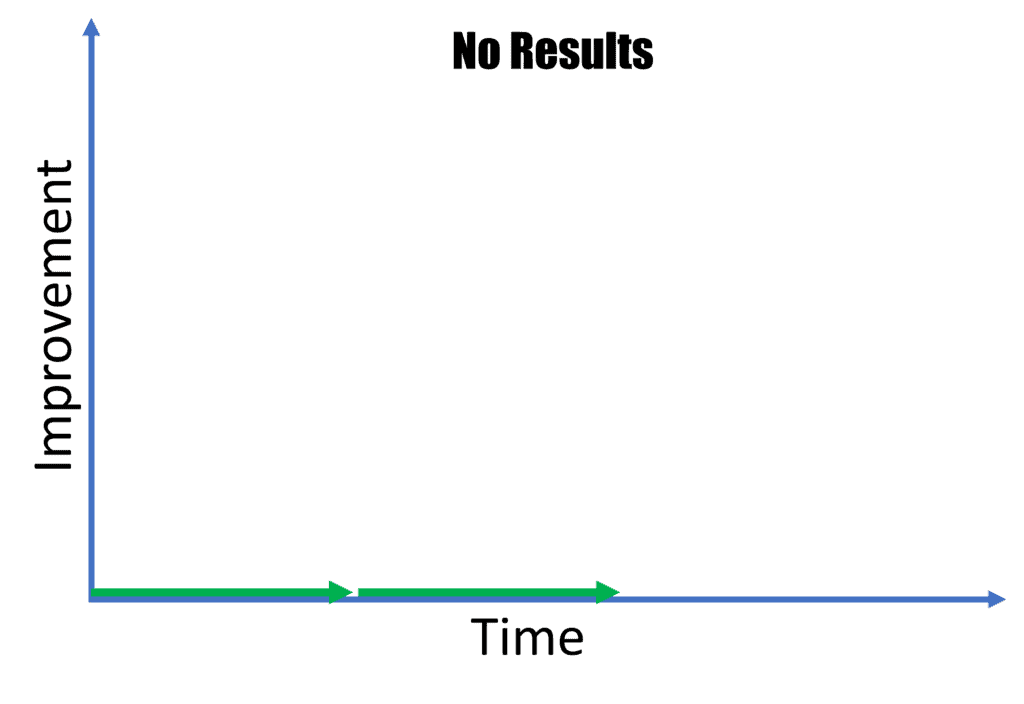

No Results

In this post-procedure trajectory, no improvement at all is observed. Obviously, this can be due to the fact that the ligament injury is just too big to be a candidate for injection-based healing enhancement. Also, rules 2-5 above also apply and should be tried before throwing in the towel.

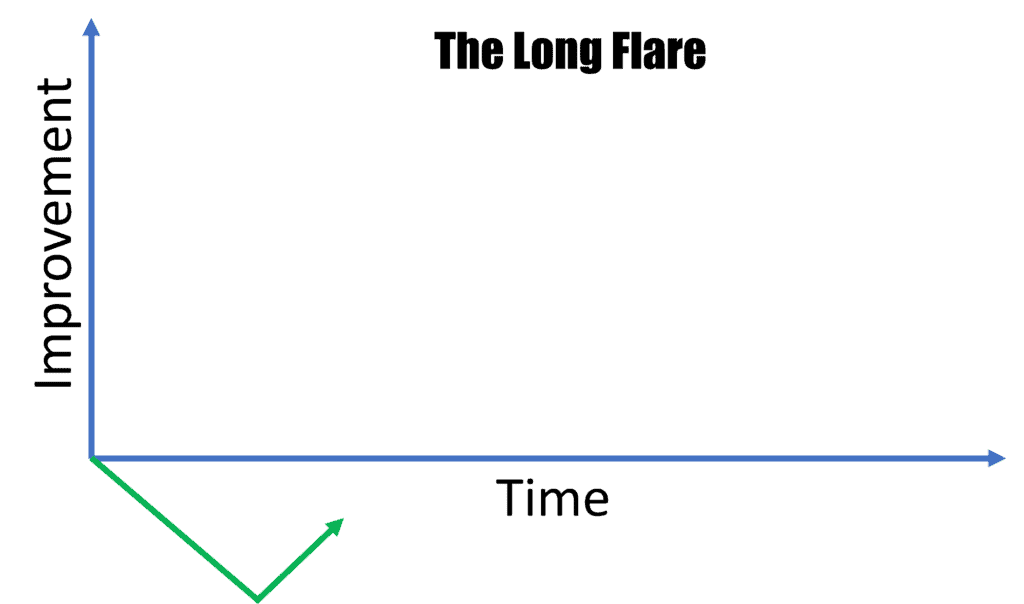

The Long Flare

In this trajectory, the patient gets worse for much longer than the average patient. For example, usually, these therapies cause a few days to a week of increased pain or soreness. However, when that flare-up lasts months or never seems to go away, the issue is usually central sensitization. That means that there has been a neurologic injury that’s big enough (like the new discovery of spinal cord injury in some car crash victims) or the nerves are ramped up so much, that the patient over-reacts to the stimulus and inflammation of injection. There are multiple possible solutions:

- Reduce systemic inflammation, see fish oil discussion above. Other things to add could also be high-dose curcumin and other anti-inflammatory supplements.

- Add a drug like Lyrica. This is a medication that’s very effective for nerve pain and can blunt this overreaction.

- Make sure the patient is fully anesthetized during the procedure (i.e. not conscious). This reduces the input to the nervous system so it reacts less.

- Less is more. Meaning, injecting fewer structures and working up to more over time usually reduces the flare-up and makes it more manageable.

The upshot? Helping ligaments heal through injections is a real thing and also a bit of an art. When all goes well, which is usually the case, then everything is easy. However, knowing what to do or how to alter things when the result is less than optimal is also a key skill in helping patients get the best possible outcome.

_______________________________________________

References:

(1) Centeno CJ, Elliott J, Elkins WL, Freeman M. Fluoroscopically guided cervical prolotherapy for instability with blinded pre and post radiographic reading. Pain Physician. 2005 Jan;8(1):67-72. PMID: 16850045.

(2) Hankenson KD, Watkins BA, Schoenlein IA, Allen KG, Turek JJ. Omega-3 fatty acids enhance ligament fibroblast collagen formation in association with changes in interleukin-6 production. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 2000 Jan;223(1):88-95. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.2000.22312.x. PMID: 10632966.

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.