Can Obesity Turn Your Spine Ligaments Into Inflexible Bone?

We know that being overweight places us at all sorts of enhanced risks for various serious diseases. We also know that it adversely impacts your spine and joints not only because of the extra forces but also because of chemical influences. New research has a new risk for the spine: your ligaments may turn to bone!

Understanding Spine Ligaments

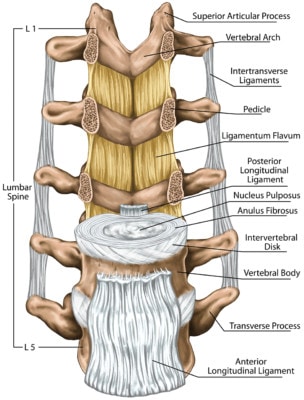

To understand the spinal ligaments, you first need to know how the spine is constructed. The spine is a gently curving column of bones called vertebrae, which as stacked one on top of the other. At the top end, it starts at the base of the skull, and at the bottom, it ends at the tailbone. There are five vertebral segments: cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacrum, and coccyx (the tailbone). The primary purpose of the spinal column is to house and secure the spinal cord, the large bundle of nerves that travels through the spinal canal (the interior of the spinal column).

A cross section of the spine. Stihii/Shutterstock

The spinal column also consists of the facet joints, which along with the disc between the bones provides flexibility. Between the vertebrae, we have discs that cushion the bones and absorb forces, and we also have spinal ligaments that stabilize and support the spinal column as well as protect the discs. The major ligaments include the ligamentum flavum, the anterior longitudinal ligament, and the posterior longitudinal ligament (see left) as well as others. The ligamentum flavum makes up the back wall of the spinal canal.

Does Obesity Cause Calcification of the Spinal Ligaments?

The new study investigated calcifications (ligament turned to bone) in spine ligaments to determine if they were associated with obesity. Calcification of a ligament means a thickening or hardening of the ligament due to a buildup of calcium deposits. Since calcification is common with aging, researchers studied younger (age 29–50) obese subjects to determine whether or not obesity alone can also cause these calcifications. Three spine ligaments were analyzed: the ligamentum flavum (LF), the anterior longitudinal ligament and annulus (ALL), and the posterior longitudinal ligament and annulus (PLL).

The results? Calcifications of two of the ligaments, the ALL and PLL, were not found to be associated with obesity; however, calcification of the third ligament, the LF, was linked only to the obesity. While age was a factor in the other two calcified ligaments, in the LF, degeneration in the ligament due to age was not a factor, and researchers concluded that obesity plays a greater role here.

Let’s learn a little more about the ligamentum flavum.

What Is the Ligamentum Flavum (LF)?

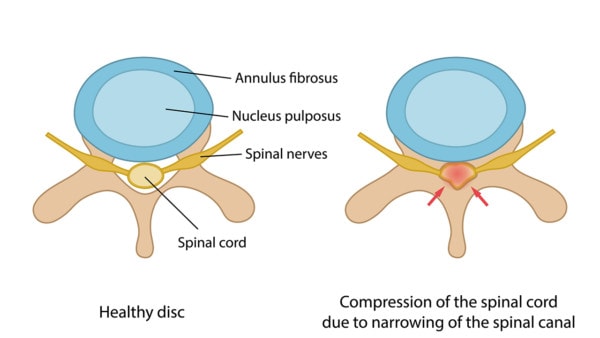

The ligamentum flavum is an important spinal ligament that lives in and forms the roof or back of the spinal canal. It can weaken or become hypertrophic, meaning enlarged, and can press on spinal nerves. I’ve shared a diagram, showing the location of the ligamentum flavum in the spine as well as explained this more in-depth in a recent spinal decompression blog post. Calcifications of the ligamentum flavum are also associated with spinal stenosis, again potentially creating pressure on the nerves that travel through the canal.

Olga Bolbot/Shutterstock

Spinal stenosis is a narrowing of the spinal canal created when ligaments become enlarged (such as by calcification) and/or when bone spurs form, which is common with arthritis. This also happens as the ligament becomes less pliable and buckles when you stand up straight or bend backward. This stenosis compresses the spinal cord and can present as severe pain in the back or legs. This pain is most prominent while standing, and may improve with sitting or forward bending; standing compresses the spinal space where the nerves live, while sitting helps open it up a bit. The fact that obesity is connected to the ligament getting stiffer and that in spinal stenosis the stiff ligament often buckles into the canal may mean that losing weight may be a good thing for these patients.

The upshot? The fact that being overweight may cause this important ligament to get stiff may help define a treatment strategy for spinal stenosis that doesn’t involve surgery. Given that there are so many other great reasons to shed weight, your heart, as well as your back, may thank you!

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.