Should I Have Artificial Disc Replacement?

If you read this blog, you know that I often write about what I experience on a day-to-day basis. Yesterday, I spoke to a patient from New York who had already had an artificial disc implanted in his back that failed and was contemplating another in his neck. Given that my neck on MRI was far worse than this patient’s, should I have artificial disc replacements (ADR) in my neck? Let’s dig in to what ADR is, and what the research shows…

What Is an Artificial Disc?

The idea behind artificial discs really starts with the disaster of back and neck fusion. Fusion surgery involves installing hardware or bone or both to fix certain spinal segments in place. This then leads to adjacent segment disease (ASD). See my video below for more information:

Enter the idea of an artificial disc. The concept is that a prosthesis will be installed where the collapsed disc once was, between the vertebrae. This will allow for better disc height as well as permitting the disc area to still move. This, in turn, will hopefully reduce ASD and allow for better outcomes.

My Neck vs. My Patient’s Neck

The problem with all invasive surgical procedures is that, eventually, surgeons get too comfortable being a bull in a china shop. Take, for example, my patient’s neck from yesterday. This patient had already had a low back ADR device installed that didn’t work (more on that below) but was about to sign up for the latest model in his neck. When I looked at his cervical MRI, I was dumbfounded. Why? My neck MRI was far worse, and we treated it with precise orthobiologic injections and no surgery. In fact, this patient’s MRI only showed some mild degenerative disc disease with his disc height at two levels going from 6 mm to 4 mm and mild to moderate stenosis at those levels. Hence, if I’m not an ADR candidate, there is no way this guy was one. So how did we get to the place where a surgeon in Europe (where he wants to go) is offering him a two-level ADR surgery? In addition, if he needs one, then why don’t I need one? Let’s explore that further.

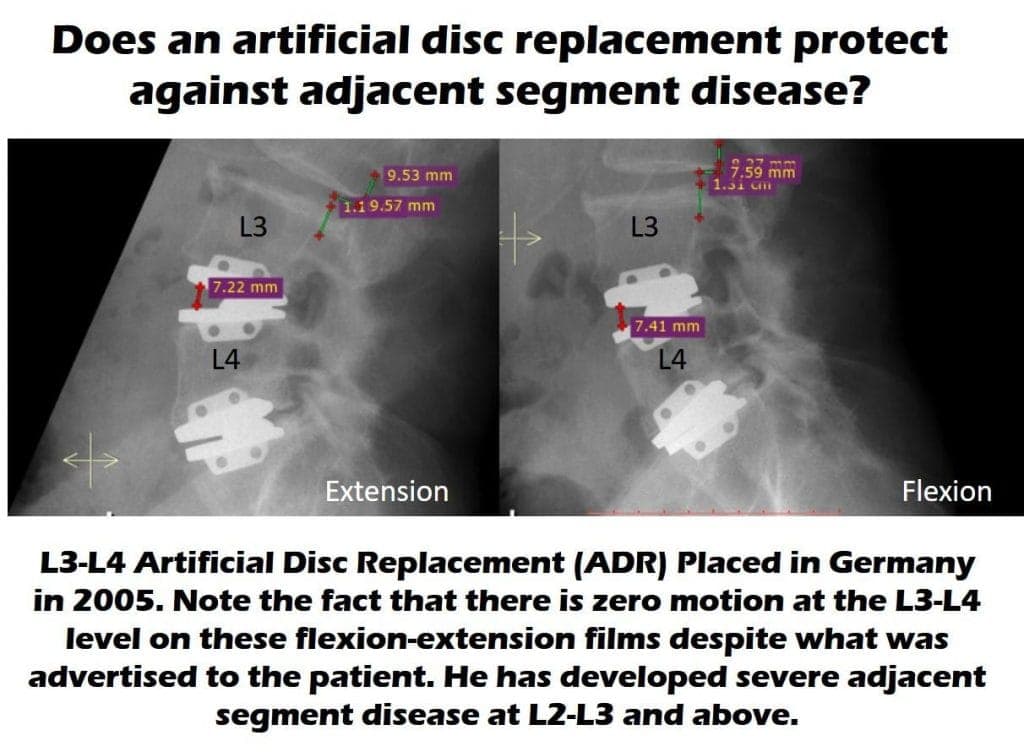

The Picture Prompts an Investigation

I’ve known for some time that ADR devices sometimes can’t beat fusion in looking at whether they cause ASD. However, the image above struck me this week as this was a patient who traveled to Europe to get two ADR devices installed in his low back. This seemed to help his pain for about 10 years, but then a work-up for newly worsened low back pain demonstrated that the level above his L3–L4 ADR device was worn out (had developed ASD). How could this happen when the device is supposed to move? Taking one look at his X-rays above was all it took to understand how it happened. His L3–L4 ADR device doesn’t move at all. Hence, to his body, it’s just like a fusion throwing abnormal forces to his L2–L3 level.

This got me thinking. What do we really know about ADR devices? How much of that comes from the companies that make them versus how much is known via research performed by uninterested parties? Let’s take a look.

The ADR Research Is All Over the Map

The first study that hit me on a US National Library of Medicine search is this one, which is a 5-year randomized controlled trial of ADR versus fusion in the neck. It concludes that there is no difference between the procedures. Then I found these studies:

- This study shows that the way the spine bones moved is changed by ADR.

- This meta-analysis concludes that a reduction in ASD can’t yet be proven when ADR is compared to fusion.

- This Swedish registry study also concluded no difference between ADR and fusion at 5 years.

Now compare those studies to this recent review of the literature that seemed to be a glowing review of the technology. On this one, the supervising author was a US neurosurgeon, so I looked up his page on the ProPublica website to see if he had received money from device manufacturers. Sure enough, he’s listed as receiving more than a million dollars in device-company payments. This is not to say that he is receiving monies from an artificial-disc manufacturer.

There are other studies comparing specific ADR devices to fusion, which all seem to show better results. However, most of these seem supported by a specific manufacturer of a specific device. I wanted to look up more physicians involved in these studies, but it seems like most of the device-company-sponsored studies are performed in China, making those physicians and their payments outside of the reach of Internet searches.

Even those studies aren’t all glowing. Take, for example, this 5-year study performed on the Prestige-LP device. This seemed to show that the Prestige artificial disc was better than a fusion spacer in terms of a reduction in ASD (8.3% vs. 22%). However, exactly one-third of patients who got the Prestige device had heterotopic ossification as a side effect of the device. What’s that? Abnormal bone growth.

Why the Formation of New Bone and a Reduction in ASD Are Nonsensical

Comparing Your Product to Fusion?

One of the common things in the research on ADR devices is a comparison to fusion. Meaning that instead of comparing the device to a sham procedure, these randomized controlled trials compare one surgical procedure to another. This is odd, given that we know that fusion is not an effective treatment for degenerative disc disease:

- Low back fusion is not effective in a review of 33 randomized controlled trials.

- Cervical fusion is no more effective than decompression alone.

So the big question is, where are the studies that compare ADR to a sham procedure? Meaning, a study that operates on some patients and then just puts others to sleep with an incision to make them believe they had the surgery? Near as I can tell, there are no such studies.

The upshot? So should I have artificial disc replacements implanted in my neck anytime soon? Not at this time. I think we’ll continue to manage my neck with orthobiologic injections for now. I would never say never, but, so far, I see some good science questioning whether ADR is all it’s cracked up to be and lots of sponsored device studies paid for by manufacturers that claim that their device is the best thing since sliced bread. Hence, let’s see how the nonsponsored research shakes out over the next few years.

Originally published on

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.