Should You Get Surgery to “Fix” Hip FAI? A Test of Construct Validity

If you read this blog, you know that I often write about what I experience on a day-to-day basis as a clinician. This weekend a hip surgeon on Linkedin and I went back and forth on the topic of why so many people without pain have FAI on their imaging and whether that means that the concept of surgery for FAI should be revisited. So today I thought I would dive deeper into this topic.

Interventional Orthobiologics (IO) vs Surgery

Regenexx has grown by leaps and bounds over the past several years. We now have 2,000+ corporations signed up to cover interventional orthobiologics instead of surgery, with many Fortune 500 companies participating. In these self-funded plans, the patient has full coverage for IO procedures instead of surgery. This saves the employer around 30-40% with high employee satisfaction and far fewer complications.

This blog began with a discussion on Linkedin about a recent study of adding PRP to hip arthroscopy surgery to treat FAI. While the study had issues like not mentioning what type or concentration of PRP was used, I brought up the obvious from the perspective of a doctor who replaces the need for these surgeries. Isn’t the real question whether we can replace the hip arthroscopy surgery in most patients with precise image-guided PRP injection?

All of this back and forth brought up yet another question. Does the published data support performing hip arthroscopy surgery to treat FAI? I had looked at this question several times before on this blog and concluded that the answer was no (see blog 1, blog 2, blog 3, blog 4, blog 5). The surgeon had a different opinion. We both posted references to research that we felt supported our opinions. Given that the surgeon posted several references I hadn’t seen before, I wanted to pull those articles and perform an in-depth analysis to see if any of those data changed my prior conclusions.

This type of question is called construct validity. Do the basic ideas underpinning the need for this surgery make common sense?

Hip FAI and Surgery

The idea behind hip Femoral Acetabular Impingement (FAI) as a diagnosis is that there are parts of the hip joint that are misshapen and cause friction with motion and this leads to wear and tear arthritis. There are two main types: cam and pincer. The idea behind a cam problem is that the femoral head is too big in places and this causes wear and tear. The idea behind the pincer type is that a bone spur that comes off of the socket (acetabulum) causes friction and damages the hip joint. One common measurement used to see if cam impingement is present is an alpha angle, which will come up throughout this discussion. The bigger the alpha angle, the bigger the cam deformity.

It’s reasonable to ask if operating on someone with FAI is a good idea or not. Especially when these surgical rates have been exploding. Take for example the concept that trimming the meniscus is a good idea. Hundreds of billions over decades were wasted on these surgeries that we now know are no better than either placebo or physical therapy (2-5).

Here are multiple studies on the question of whether hip arthroscopy surgery to treat FAI is effective:

- The satisfaction rate for hip arthroscopy to treat FAI in patients >50 years old is a very low 54%. 27% of cases went on to other surgeries like hip replacement (12).

- A 2016 review questioned whether we have evidence of efficacy for surgery to treat FAI (13).

- No differences between a surgically treated group and a non-surgical control group in this study (14).

- A failed RCT on military active duty patients being surgically treated for FAI when compared to physical therapy (15).

- A successful RCT for patients over the age of 40 when tested against physical therapy alone (16).

In particular, like most surgeries, we don’t have a sham or placebo study for surgery to treat FAI. That’s critical, as the sham procedure studies for menisectomy are what began to unravel the myth that the procedure worked. Why? Because the placebo effect of surgery is huge (17).

Tackling this Question

Let’s look at what commonly happens clinically with patients in this space. The patient begins to experience hip pain and ultimately is sent to an orthopedic surgeon when medications and PT fail. An MRI shows FAI and then the patient is operated on based on two key concepts. The first is that the FAI is causing their hip pain and the second is that if the FAI is left untreated, the patient will develop severe hip arthritis.

Therefore, how would one tackle the question of whether surgery for FAI even makes common sense? There are two key questions:

- Do FAI measurements accurately identify people with hip pain?

- Do FAI measurements accurately identify people who are highly likely to require eventual hip replacement?

FAI Imaging Sensitivity and Specificity

The first question to be answered is obvious, does the diagnostic testing we’re using to determine if someone has FAI find patients with hip pain? In other words, for any diagnostic test to be valid, it has to be sensitive and specific. Sensitive means that if you have the diagnosis, the test is very likely to show positive. Specific means that the test will be negative if the patient doesn’t have the disease.

Remember, the disease here is painful hip FAI. For MRI or X-ray to be good tests, FAI shouldn’t be found in patients without hip pain or these findings should be rare. If FAI is found in patients without hip pain, then the test has a high false positive rate and is by any medical definition a bad diagnostic test.

What does the research say on this topic?

- A large study looked at 2,081 young adults without hip pain (6). They found that more than 50% had at least one measurement consistent with hip FAI. Several common FAI radiographic signs were present in about a quarter of the participants.

- A US study demonstrated that about a quarter of the hips of people without hip pain had FAI (7).

- A recent study of 1,878 asymptomatic hips found that the cam impingement was present in 30% and pincer in 24% of the joints (8).

Based on these data, the false positive rate of diagnosing FAI on imaging is approximately 25-50%. Given that a good diagnostic test has a false positive rate of 5% or less, the idea that you can use imaging to diagnose someone with hip pain with FAI is not valid. That’s because a myriad of other musculoskeletal problems can also cause hip pain.

FAI Imaging and Longitudinal Changes

When confronted with the poor specificity of FAI imaging for diagnosing hip pain, many surgeons will state that the real utility of hip arthroscopy to get rid of FAI is that it reduces the likelihood of future problems. The idea is that if the patient has pain and is performing activities that lead to wear and tear, the surgeon will do the patient a great service by “cleaning out” the problem. This often means an invasive hip reconstruction surgery where bone spurs are removed and the labrum is reconstructed.

What do we know about patients diagnosed with hip pain and FAI and how they fare through the years? For this concept of proactive hip surgery to be valid, we would first need to know if a patient with hip pain and FAI is much more likely to get severe arthritis. To suss that out, we would need a longitudinal study, where FAI patients are followed through time for many years to see if they predictably get worse.

I had posted the first study below and the surgeon with the opposite opinion about FAI hip surgery posted the next three studies. Hence, let’s explore each one to see if they answer this important question.

- First up is a nationwide prospective study performed in the Netherlands (9). Here the researchers took 720 middle-aged to early elderly (mean 56 yrs with a range of 52-62 years old) individuals who had symptoms of early hip osteoarthritis (no or doubtful OA on imaging) and performed baseline, 2-year, and 5-year x-rays. Over the 5 years, 11% of patients with an abnormal alpha angle and cam deformity developed a progression of their hip arthritis. That’s a bit of a concern, in that 89%+ of patients with a cam deformity did not progress to the type of arthritis that requires a hip replacement. How about pincer deformity? That was not predictive of developing hip arthritis and instead was protective of arthritis progression.

Right off the bat here we see a big problem. First, based on these results, cutting off a pincer deformity would be a bad idea. On a cam deformity, if we were performing surgery to save half of the patients from needing a hip replacement in 5 years, that would be worth the cost and the risk. However, it doesn’t take a healthcare economist to understand that a pricey surgery to save 11 in 100 patients from needing a pricey surgery is not smart. In addition, none of that includes the relative patient risk calculus of operating 100 patients to prevent 11 hip replacement surgeries.

Now the paper did find that if you added in poor internal rotation of the hip with an abnormal alpha angle you could get to just under 50/50 predictive power, but there’s a catch. As any clinician can tell you, decreased hip range of motion is a finding that identifies hip osteoarthritis patients. So all the authors are doing here is to find those hip pain patients with more osteoarthritis at the outset.

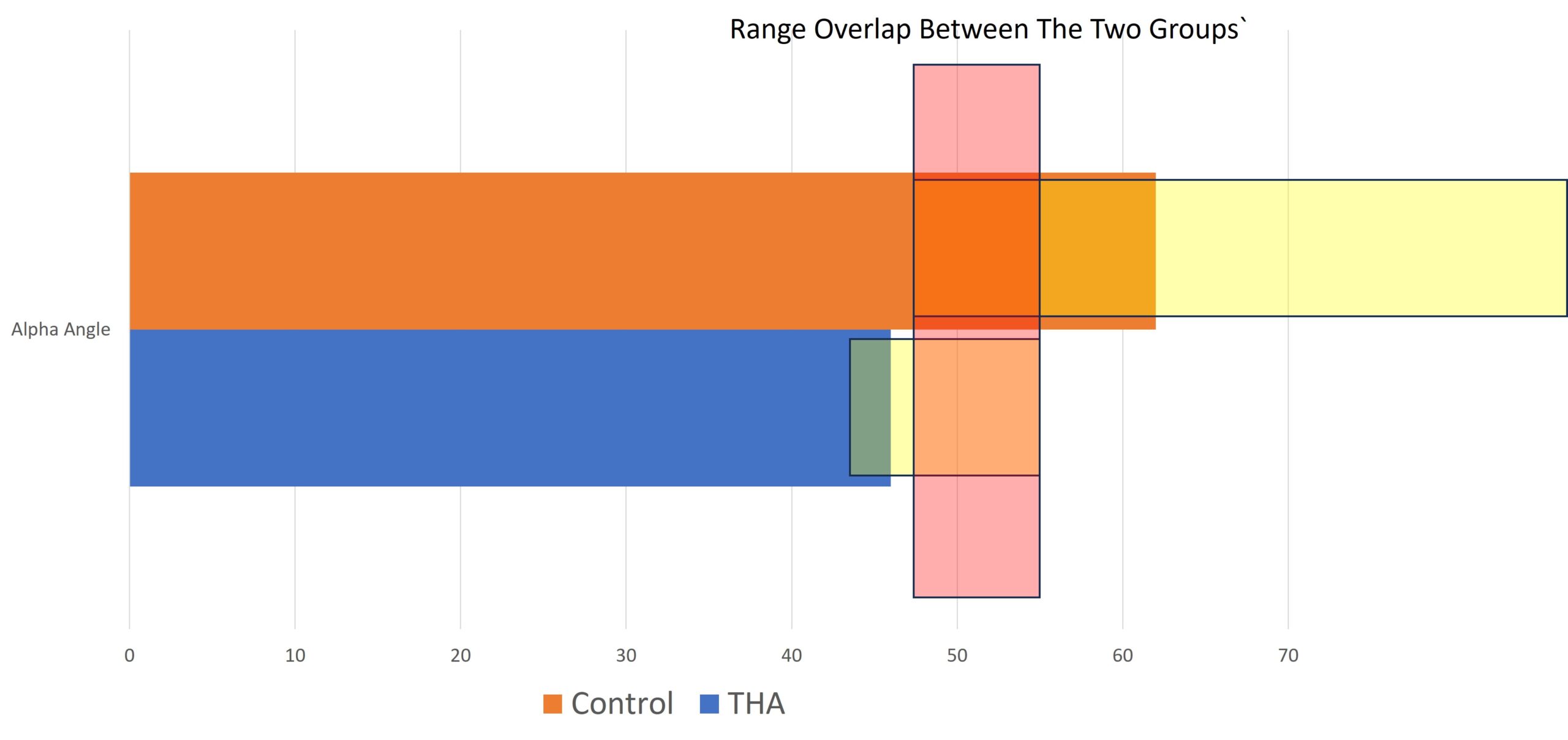

- Next up is a study that curiously only looked at middle-aged to early elderly, asymptomatic women (mean age of 55 with a range of 50-60) (11). In the second year of this 20-year study, they looked at 25 hip joints that had received a THA versus 243 that had not. So right away we have a much smaller study here as these are hips and NOT patients. It looks like these represent about 12 patients who converted to THA. We also have a second problem, as the first study found out what percentage of hips that met FAI criteria converted to severe hip arthritis at 5 years, this study starts with a hip replacement as its outcome. This means that I can’t find the percentage of people who didn’t convert to a hip replacement like we can in the first study. Be that as it may, the real problem is that the measurement intervals are a mess and overlap badly. Let’s explore that more deeply.

Let’s look at the alpha angle. The good news is that the control group’s hips have a normal mean alpha angle of 46 degrees while the few patients who converted to hip replacement have hips with an abnormal mean alpha angle of 62 degrees. While that’s a statistically significant difference, the range of the standard deviation badly overlaps as shown below (SD range in yellow and the overlap in red). This means alpha angle is not a great test to differentiate these two groups as you can have patients who live in that overlap who are determined to be part of one group when they should be in the other. For example, an alpha angle of 50 degrees could belong to someone who converted to a hip replacement or someone who did not.

The authors try several different statistical techniques here to try and find other associations, but with about 12 real patients converting to THA over 20 years and the overlaps reported in all of the data, IMHO it’s a fool’s errand. For example, the study purports to find that pincer deformity was associated with a hip replacement, but the first study above has 3X the number of cases converting to hip replacement, so its results would be more reliable than this much smaller study.

- Next up is an even smaller study that looked at 120 patients who were early elderly (mean age 62 years) with about 35 patients who had moderate arthritis that developed to severe over 6-13 years. The control group also had moderate arthritis, but that did not advance during this time and this included about 80-90 patients. While some moderate associations were found here in FAI measurements and advancement in arthritis, this is a group of early elderly patients with moderate hip arthritis who are not candidates for hip arthroscopy as that procedure is ineffective in this group (11).

- Finally, we have a large Dutch study who were part of an OA tracking cohort of early elderly patients (Mean age 60-61). A number of different types of FAI were determined including pincer (pistol grip deformity). This was not a longitudinal study that looked at patients over time, but a snapshot in time, cross-sectional investigation. They found no association between a pincer deformity and the patient having groin pain (a common hip arthritis pain complaint). They did find a relationship between this pincer deformity and arthritis, but since this bone spur is one feature of osteoarthritis, it’s unknown what conclusions can be drawn from that finding. The authors acknowledged that there is no way to draw any conclusions about cause and effect based on their study.

Which of these studies most represents the type of patients that show up to orthopedic practices with hip pain and get diagnosed with FAI? The first study, in that patients in pain walk into medical practices looking for help. Also, given that these patients had no to very mild arthritis, they could be reasonable hip arthroscopy patients. The second study doesn’t apply to that same discussion as these patients had no pain, so they are not the type of people who walk in looking for hip surgery. The third group represents early elderly patients with moderate hip arthritis who are not hip arthroscopy candidates.

From the data in this section, we can conclude that we don’t have strong data that shows that operating on patients with hip pain and FAI is a reasonable way to avoid hip replacement. The only study that even applies to this argument shows that only 11% of patients with one type of FAI (cam Impingement) will develop severe hip OA over 5 years. So operating on 100 patients to avoid a hip replacement in 11 is not reasonable.

The Chicken or the Egg?

There’s another problem that has always plagued FAI metrics which is proving causation. Meaning surgeons conceptualize these cam and pincer abnormalities as being causative of hip arthritis. You can see from the data above that’s probably not accurate for a pincer deformity and not very accurate for a cam deformity. What if these findings are just indicative of early hip arthritis and not causative at all? Then removing these pieces of bone and reshaping the hip would be a fool’s errand. It would also make any longitudinal study looking for the development of arthritis invalid as merely having one of these abnormalities just picks out the cases that already have early arthritis.

The upshot? In 2023, the data supporting that operating on patients with hip pain who have abnormal FAI measurements is weak. Meaning that the construct validity test failed. Maybe better data will be developed or there is some study that’s better out there, but so far I haven’t seen that information. In addition, because of this data, you have to reasonably ask yourself, what came first, the chicken or the egg?

____________________________________________________

(1) Westermann RW, Day MA, Duchman KR, Glass NA, Lynch TS, Rosneck JT. Trends in Hip Arthroscopic Labral Repair: An American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery Database Study. Arthroscopy. 2019 May;35(5):1413-1419. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2018.11.016. Epub 2019 Apr 9. PMID: 30979629.

(2) Finnish Degenerative Meniscal Lesion Study (FIDELITY) Group. Arthroscopic Partial Meniscectomy versus Sham Surgery for a Degenerative Meniscal Tear. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:2515-2524

(3) Katz JN, Brophy RH, Surgery versus Physical Therapy for a Meniscal Tear and Osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1675-1684

(4) Sihvonen R, Englund M, Mechanical Symptoms and Arthroscopic Partial Meniscectomy in Patients With Degenerative Meniscus Tear: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. [Epub ahead of print 9 February 2016]164:449–455. doi: 10.7326/M15-0899]

(5) Risberg MA, Degenerative meniscus tears should be looked upon as wrinkles with age—and should be treated accordingly. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2014;48:741.

(6) Laborie LB, Lehmann TG, Engesæter IØ, Eastwood DM, Engesæter LB, Rosendahl K. Prevalence of radiographic findings thought to be associated with femoroacetabular impingement in a population-based cohort of 2081 healthy young adults. Radiology. 2011 Aug;260(2):494-502. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11102354. Epub 2011 May 25. PMID: 21613440.

(7) Jung KA, Restrepo C, Hellman M, AbdelSalam H, Morrison W, Parvizi J. The prevalence of cam-type femoroacetabular deformity in asymptomatic adults. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011 Oct;93(10):1303-7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B10.26433. Erratum in: J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011 Dec;93(12):1679. PMID: 21969426.

(8) Morales-Avalos R, Tapia-Náñez A, Simental-Mendía M, et al. Prevalence of Morphological Variations Associated With Femoroacetabular Impingement According to Age and Sex: A Study of 1878 Asymptomatic Hips in Nonprofessional Athletes. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. February 2021. doi:10.1177/2325967120977892.

(9) Agricola R, Heijboer MP, Roze RH, Reijman M, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Verhaar JA, Weinans H, Waarsing JH. Pincer deformity does not lead to osteoarthritis of the hip whereas acetabular dysplasia does: acetabular coverage and development of osteoarthritis in a nationwide prospective cohort study (CHECK). Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013 Oct;21(10):1514-21. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.07.004. Epub 2013 Jul 9. PMID: 23850552.

(10) Nicholls AS, Kiran A, Pollard TC, Hart DJ, Arden CP, Spector T, Gill HS, Murray DW, Carr AJ, Arden NK. The association between hip morphology parameters and nineteen-year risk of end-stage osteoarthritis of the hip: a nested case-control study. Arthritis Rheum. 2011 Nov;63(11):3392-400. doi: 10.1002/art.30523. PMID: 21739424; PMCID: PMC3494291.

(11) Lei P, Conaway WK, Martin SD. Outcome of Surgical Treatment of Hip Femoroacetabular Impingement Patients with Radiographic Osteoarthritis: A Meta-analysis of Prospective Studies. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019 Jan 15;27(2):e70-e76. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00380. PMID: 30256340.

(12) Perets I, Chaharbakhshi EO, Mu B, Ashberg L, Battaglia MR, Yuen LC, Domb BG. Hip Arthroscopy in Patients Ages 50 Years or Older: Minimum 5-Year Outcomes, Survivorship, and Risk Factors for Conversion to Total Hip Replacement. Arthroscopy. 2018 Nov;34(11):3001-3009. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2018.05.034. Epub 2018 Oct 6. PMID: 30301626.

(13) Fairley J, Wang Y, Teichtahl AJ, Seneviwickrama M, Wluka AE, Brady SRE, Hussain SM, Liew S, Cicuttini FM. Management options for femoroacetabular impingement: a systematic review of symptom and structural outcomes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016 Oct;24(10):1682-1696. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.04.014. Epub 2016 Apr 20. PMID: 27107630.

(14) Lodhia P, Gui C, Martin TJ, Chandrasekaran S, Suárez-Ahedo C, Walsh JP, Domb BG. Arthroscopic Central Acetabular Decompression: Clinical Outcomes at Minimum 2-Year Follow-up Using a Matched-Pair Analysis. Arthroscopy. 2016 Oct;32(10):2092-2101. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.04.015. Epub 2016 Jul 2. PMID: 27378389.

(15) Mansell NS, Rhon DI, Meyer J, Slevin JM, Marchant BG. Arthroscopic Surgery or Physical Therapy for Patients With Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial With 2-Year Follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2018 May;46(6):1306-1314. doi: 10.1177/0363546517751912. Epub 2018 Feb 14. PMID: 29443538.

(16) Martin SD, Abraham PF, Varady NH, Nazal MR, Conaway W, Quinlan NJ, Alpaugh K. Hip Arthroscopy Versus Physical Therapy for the Treatment of Symptomatic Acetabular Labral Tears in Patients Older Than 40 Years: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Sports Med. 2021 Apr;49(5):1199-1208. doi: 10.1177/0363546521990789. Epub 2021 Mar 3. PMID: 33656950.

(17) Wartolowska K, Judge A, Hopewell S, Collins G S, Dean B J F, Rombach I et al. Use of placebo controls in the evaluation of surgery: systematic review BMJ 2014; 348 :g3253 doi:10.1136/bmj.g3253

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.