The Healthy Discs in Your Low Back Are Full of Bacteria?

Every so often you come across a scientific article that so challenges what doctors think they know that it blows your mind. That just happened today when I ran across an article that showed that our low back discs are filled with bacteria just like the microbiome in our guts! The mind-blower? Physicians are taught that normal discs were sterile. This literally changes everything.

Low Back Discs

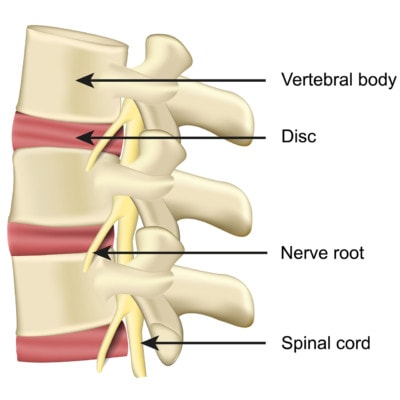

Medicalstocks/Shutterstock

The discs in your low back and spine are like shock absorbers between the bones. They are called intervertebral discs because they live between the vertebrae. They have a tough outer covering known as the annulus fibrosis and an inner gel-like substance called the nucleus pulposis.

Sterile Discs

We, physicians, were taught in medical school, residency, and fellowship that low back and spinal discs are sterile, meaning devoid of bacteria. In fact, if they had bacteria, that could only be because of a nasty infection. For example, IV drug users will sometimes show up to emergency rooms with low back disc infections. The idea is that the bacteria is seeded there by the drug user’s needle.

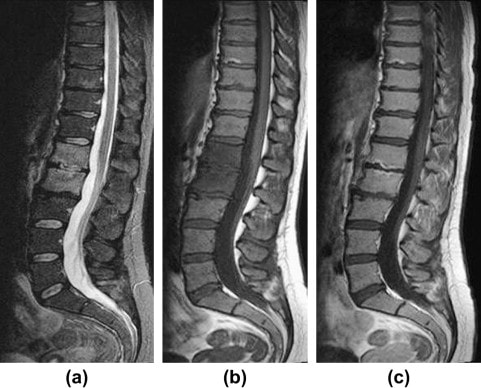

Discitis

Discitis can be caused by a disc injection or surgery. When it happens, you often see the two adjacent vertebrae turn all white on a water-based MRI image (T2) or dark on other types of spinal MRI imaging. The problem is that the bacteria can literally eat away at the vertebrae. Treatment often requires surgery and/or long-term antibiotics.

Do Some People Have Bacteria in their Discs?

Before the new study below was published, we had some research showing that when surgeons take samples of degenerated discs. they sometimes grow out bacteria. For example, one recent study found that in 11% of patients undergoing surgery for a herniated disc, p acnes was detected (1). This is surprising to us physicians as none of these patients had discitis. There are also scientists now convinced that p. acnes infection causes discs to degenerate and leads to degenerative disc disease (DDD) (2).

The New Research

The researchers in the new study did something very different from past studies (3). They used a new technology that can detect the genetic signature of thousands of common bacteria in hours (16SrRNA sequencing). They also used the disc tissue of brain dead patients, hence their bodies were still alive, but they were legally dead. Hence, they could harvest allot of disc tissue from many discs for the study. Both of these were very different from past studies which were limited by what would grow in culture (rather than detecting a genetic signature for many bacteria) and by the fact that disc material could be taken from live patients only in specific circumstances (i.e. during an already planned surgery).

What did they find? An array of 424 different bacteria in healthy discs. Basically, they found a microbiome in discs just like the one that exists in your gut! Protective bacteria were more abundant in normal discs, and bad bacteria were more abundant in degenerative and herniated discs. P. acnes was present in all three types of discs.

Here’s the really freaky part. Fifty-eight bacteria were found in common between the gut and the disc! There were 29 in common between the skin and the disc.

Is Discitits an Imbalance of Good versus Bad Flora?

We know that the composition of your gut microbiome impacts everything from your cognitive function to your immune system to depression (4). We also know that antibiotics negatively impact your gut bacteria (5). So is discitis not really an infection because the disc was never really sterile but instead an overgrowth of p. acnes (bad bacteria) in relationship to good bacteria?

Is DDD Explained by that Same Imbalance?

There have been a number of studies through the years that have used antibiotics to treat DDD (6). Several have shown that long-term courses of antibiotics can reduce the symptoms of low back pain in patients with DDD and Modic changes. Does this work because it reduces the number of bad bacteria? Have these results been hit and miss because the wrong antibiotic was used that also killed the good bacteria?

Should We Be Augmenting Discs with Good Bacteria?

Transplanting good bacteria from patients with healthy guts into those with problems like chronic C. difficile infection has been very effective (7). In this case, we often see normal discs above and below the “bad disc”. Could transplanting some of the bacteria from a “good” disc into a “bad” disc help the bad disc?

The upshot? This paper made my head explode with the possibilities. This is one that will likely change how we approach the treatment of DDD and back or neck pain and in the process, may reinvent our therapeutic targets. Meaning rather than trying to regrow disc tissue, should we be trying to rebalance the disc microbiome?

__________________________

References:

(1) Capoor MN, Ruzicka F, Machackova T, et al. Prevalence of Propionibacterium acnes in Intervertebral Discs of Patients Undergoing Lumbar Microdiscectomy: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0161676. Published 2016 Aug 18. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0161676

(2) Slaby O, McDowell A, Brüggemann H, et al. Is IL-1β Further Evidence for the Role of Propionibacterium acnes in Degenerative Disc Disease? Lessons From the Study of the Inflammatory Skin Condition Acne Vulgaris. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:272. Published 2018 Aug 14. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2018.00272

(3) Rajasekaran, S., Soundararajan, D.C.R., Tangavel, C. et al. Human intervertebral discs harbour a unique microbiome and dysbiosis determines health and disease. Eur Spine J (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-020-06446-z

(4) Barko PC, McMichael MA, Swanson KS, Williams DA. The Gastrointestinal Microbiome: A Review. J Vet Intern Med. 2018;32(1):9‐25. doi:10.1111/jvim.14875

(5) Cresci GA, Bawden E. Gut Microbiome: What We Do and Don’t Know. Nutr Clin Pract. 2015;30(6):734‐746. doi:10.1177/0884533615609899

(6) Albert HB, Sorensen JS, Christensen BS, Manniche C. Antibiotic treatment in patients with chronic low back pain and vertebral bone edema (Modic type 1 changes): a double-blind randomized clinical controlled trial of efficacy. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(4):697‐707. doi:10.1007/s00586-013-2675-y

(7) Liubakka A, Vaughn BP. Clostridium difficile Infection and Fecal Microbiota Transplant. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2016;27(3):324‐337. doi:10.4037/aacnacc2016703

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.