Treating the Functional Spinal Unit: Time to Get Rid of the Pain Generator

Interventional pain medicine teaches us that we need to find what I call “the magic pain generator.” Meaning we have a whole specialty of physicians (which used to include me) whose focus is trying to find one structure in the spine that’s causing most of the patient’s spinal pain. However, while sometimes this can be done, oftentimes, this narrow thinking leads us to the wrong conclusion about how best to help the patient. In fact, in the age of regenerative medicine, we need to throw this concept out the proverbial window. Let me explain.

The Functional Spinal Unit

We’ve known since the 1970s, when White and Panjabi’s seminal text put it all together, that each of the 24 levels of the spine (neck, upper back, and lower back) is more than just single parts, but acts as one machine. That’s called the functional spinal unit (FSU). The goal of the machinery is to provide a stable base of support for the rest of the body, like the steel in a skyscraper. Unlike that building, however, the spine also has to actively bend, so the systems are far more complex than structural steel.

The FSU is made up of lots of parts, which include the disc, facet joints, ligaments, bones, and muscles. Each has an important job in providing stability. To learn more about what all of these parts do, please take a few minutes and see my video below as it will bring this whole topic together:

The Magic Pain Generator

We have a problem in pain management that desperately needs to be fixed. The good news is that the new concepts that drive regenerative medicine are changing the way some of these physicians approach patients; the bad news is that we have decades of bad practice to erase. That poor medicine is what I call “the magic pain generator.”

The idea is that it’s the doctor’s job to find one thing in the spine that hurts. This could be the disc, spinal nerve, facet joint, or SI joint (to find out what these are and what they do, watch the video above). Once identified, the goal is to inject steroids into it or nuke the nerves that carry pain signals from it or block those pain signals with a stimulator.

So what’s the problem? The big issue is that in an age when repairing the damage is becoming increasingly possible, knowing what hurts is not as important as knowing why.

Knowing Why Someone Hurts Is All About the FSU

Today, if you walk into a pain management clinic (even one that learned how to inject PRP or stem cells in a weekend course) and they ID that your facet joints at L4–L5 hurt, the concept of why those joints are painful will go over your physician’s head to your detriment. Meaning the joints may have arthritis, but why did that happen? Let me use this example below to explain.

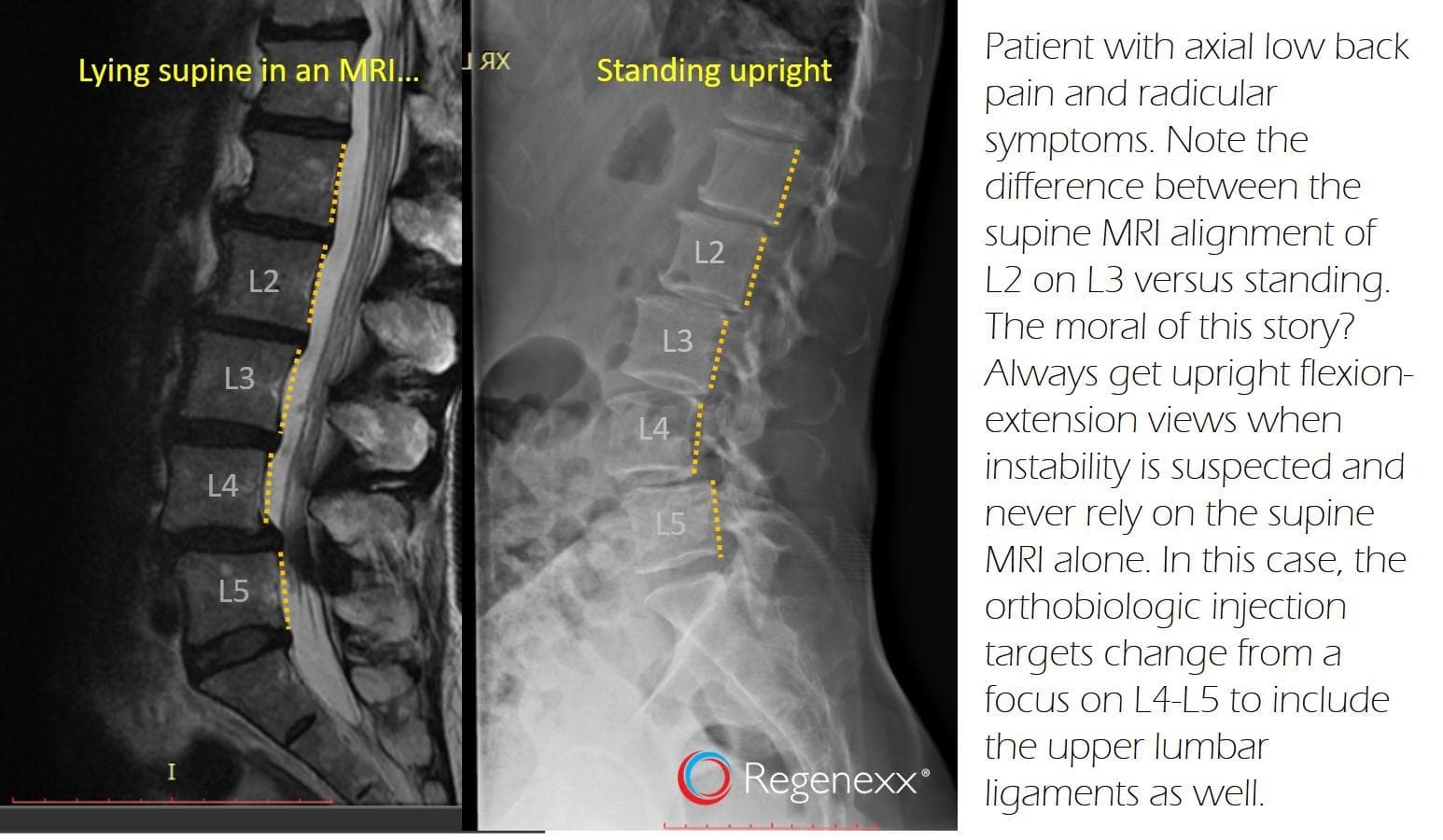

The image on the left is an MRI of a patient lying face up in a tube. Notice that the L4 vertebra is forward on the L5 (look at the yellow dotted lines at the back of the vertebrae which should line up). So if this patient has painful L4–L5 facets, the pain management doctor will just inject those facets (whether that be with steroid, PRP, or stem cells). This might help for a while, but there’s a reason those facets hurt, and that’s because this segment is unstable.

When a level is unstable, that means it moves around too much. The joints in this scenario get beat up over time. Hence, the ligaments and muscles that hold that L4 vertebra back need help. So the regenerative medicine approach would be to inject not only the facet joints with a substance like PRP that can help the pain and increase healing but also the ligaments and muscles as well.

Now let’s look at the image on the right. This is what happens when the patient stands. The bones that were well aligned when lying face up (L2, L3, and L4) are now slipping forward and backward, again indicating instability. So the area that needs to have ligaments and muscles treated, as well as painful joints, just got more extensive simply by taking a picture of the patient when standing and not relying only on the MRI.

What’s the Data that the Magic Pain Generator Idea Is All Washed Up?

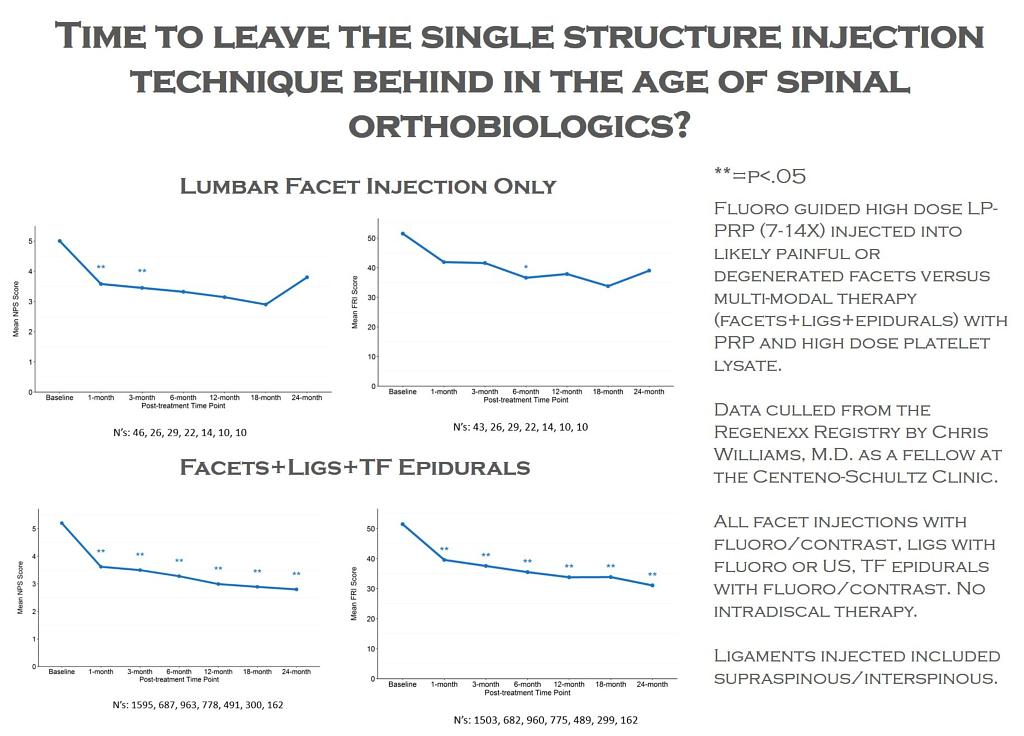

One of our ex-fellows, a brilliant physician who is now transitioning from Colorado to Atlanta (Chris Williams, MD), decided to look at this issue in our advanced registry. This is a system where we have been tracking specific types of treatments and how they work or don’t work going back to 2005. What Chris did was to pull the patient cases where we injected only the facet joints with PRP, basically the magic pain generator approach. He then compared those patient results to those patients where we used an FSU treatment, meaning we injected the irritated joints, nerves, and ligaments. The results are below:

Note that the two graphs above are pain and function graphed over time for patients who just had their low-back facets injected with PRP (facets). In this case, in both graphs, we want to see that line go down and stay down over time. It kind of does that, but compare that downward trend to the line in the two graphs below where the whole FSU (facets, ligs, TF epidurals) was treated with platelets. The line in the bottom two graphs goes down more convincingly and stays down over time. Meaning that in this data set, more treatment of more things seems to be better, which is what we have observed clinically as well.

The upshot? The age of regenerative medicine allows us to start asking why our patients hurt and to begin treating those issues rather than just treating what’s causing the pain. While in some patients, single-structure treatment with PRP or stem cells might be appropriate because that part was hurt in a traumatic event, like a car crash, for most patients, we strongly believe that treating the whole FSU beats just treating one part.

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.