Don’t Count on ACL Surgery to Prevent Arthritis

ACL reconstruction surgery has become like a rite of passage for athletic kids and adults. However, what if the research showed it didn’t work? Meaning the only real reason to undergo the invasive surgery is to prevent problems from occurring down the line. Now a new study adds to the body of evidence that the procedure doesn’t prevent arthritis. So why are we drilling holes in knees and harvesting and installing tendons?

The Idea Behind ACL Surgery

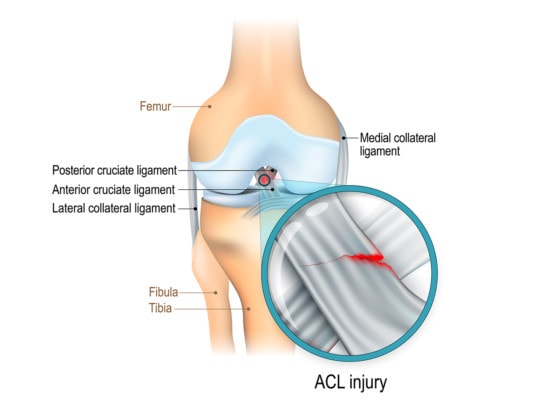

Designua/Shutterstock

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is a strong stabilizer of the knee that lives inside the structure. It can be torn during athletic activities, and many patients these days end up in surgery when that happens. The concept behind repairing the ligament is that with a torn ACL, the knee is unstable. This instability can lead to arthritis, so the idea is that by surgically replacing the ACL, we’re reducing the likelihood that the knee will get arthritic.

The Problems with ACL Surgery

Despite being a really common surgery, we know, based on the research, that all is not rosy in ACL surgery land. Take the following examples:

- Less than 1 in 5 athletes are ready to return to play by eight months after ACL surgery.

- ACL surgery shortens and not lengthens professional careers.

- The single-bundle technique that’s often used to reconstruct the ACL leaves the joint rotationally unstable, as the normal ligament has two bundles that stabilize the joint.

- There is a loss of normal position sense and performance in the knee after ACL surgery.

- The likelihood of retearing the ACL graft or the other ACL goes up after surgery.

- Two-thirds of teens who get ACL surgery will have arthritis by age 30.

What Do Prior Studies Say About the Effectiveness of Reconstructing the ACL?

Many national health systems now have policies that recommend conservative care before surgery to treat ACL tears. Why? Studies like this 143-patient investigation where patients with ACL tears who had surgery were compared to patients who did not. In this case, the patients who didn’t opt for surgery were more able to get back to sports in their first year after injury. At the end of two years, there was no difference in return to sports.

“For adults with acute ACL injuries, we found low-quality evidence that there was no difference between surgical management (ACL reconstruction followed by structured rehabilitation) and conservative treatment (structured rehabilitation only) in patient-reported outcomes of knee function at two and five years after injury.”

The group went on to say that in the largest study they reviewed, since there were patients who opted not to get surgery who later still decided to get surgery, the question can’t be fully answered until two ongoing and larger higher-quality trials are completed. This is because we can’t tell, based on the study design, if their decision to get the surgery was based on symptoms, peer pressure from coaches or players, or something else.

What Do Prior Studies Say About Knee Arthritis After ACL Surgery?

One of the reasons to get the surgery is to protect the knee from arthritis. However, the surgery may not be very good at preventing arthritis. For example, a recent long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of knee ACL surgery showed that the ACL-operated knee got arthritis at three times the rate of the nonoperated knee.

What Does the New ACL Surgery Study Say?

The new study was published last month and looked at 154 patients in Holland who had complete ACL tears where 50 were treated without surgery and the rest received the ACL reconstruction procedure. After two years, MRIs showed that opting to get the knee ACL surgery did not protect you from arthritis, as there was no difference in the arthritis rates of the surgery and no-surgery groups.

The Upshot? The research supporting knee ACL surgery for a tear is weak at best. If the athlete can avoid the surgery, there seems to be little difference in arthritis rates, meaning the surgery clearly doesn’t protect the knee. In addition, based on the research we have now, return to play in the first year is faster without the surgery. If the athlete can’t return to play without surgery, our early research suggests about 70% can be treated with a precise image-guided injection of their own stem cells. We have a second and larger MRI case series that will be published later this year as well as the first set of results from our randomized controlled trial.

If you have questions or comments about this blog post, please email us at [email protected]

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.