A New Neck Ligament Has Big Implications for CCJ Instability Patients

The idea that the covering of the brain and spinal cord (the dura) is jacked into muscles and ligaments seems alien to physicians. After all, we were taught that the dura was a separate structure that protected the brain and, hence, was isolated from everything else. Turns out that this concept isn’t even remotely true, as several research studies have now shown that muscles and ligaments connect the outside world to the dura. All of this research has major implications for CCJ instability and trauma patients. Let’s review.

Understanding the Dura and the CCJ

CCJ stands for cranial cervical junction, which is the place where the head meets the spine. There are strong ligaments that hold the head on that can become loose with disease and aging or damaged by trauma. This results in the upper neck becoming unstable, which means things like joints move around too much and other structures like muscles/tendons get yanked on too much. All of that, over time, can cause damage and pain to these structures.

The dura is the covering of the brain and spinal cord. It holds the fluid (cerebrospinal fluid, or CSF) that circulates around the brain and has a nerve supply, so it’s pain sensitive. As I suggested above, we doctors have been taught that the dura is isolated from the outside world and that this makes up one of the protection mechanisms for the brain and spinal cord. However, it turns out that none of this is true, and the fact that muscles and ligaments are connected to the dura has major implications for patients with CCJ instability and/or upper neck trauma. So let’s review what we know.

Muscles Jacked into Your Brain and Spinal Cord

The first discovery that the dura was connected to outside structures came from neurosurgeons who noted that cutting through the upper neck muscles to get access to the skull base area could relieve headache pain. They performed dissections and found that the rectus capitus posterior minor (RCPMin) connected directly to the dura. This had major implications for headache patients as it meant that a spasm in the upper neck muscles could yank on the pain-sensitive covering of the brain and directly produce headaches.

Figuring Out How the Body Is Connected Is Much Harder than You Would Think

If you want to find out what’s connected to what, you can just perform a cadaver dissection, right? This works for most of the major parts and pieces, but, regrettably, the fine details are often lost, regardless of how good the anatomist. Why? Pulling things apart, no matter how delicately you try to accomplish it, is destructive.

In the ’90s and early 2000s, a new technique for preserving the body became available called plastination. You probably have seen billboards or exhibits that went by the name “Body Worlds” where plastinated bodies were posed and dissected to show the dynamic workings of muscles, tendons, and ligaments. However, long before that, this technique of fixing biologic specimens with epoxy and slicing them had been used by anatomists to find structures that can’t be easily seen on dissection or are too fine to be preserved. This technique has now shown new ligaments that are also jacked into the dura.

The New Ligaments That Connect the Neck and the Dura

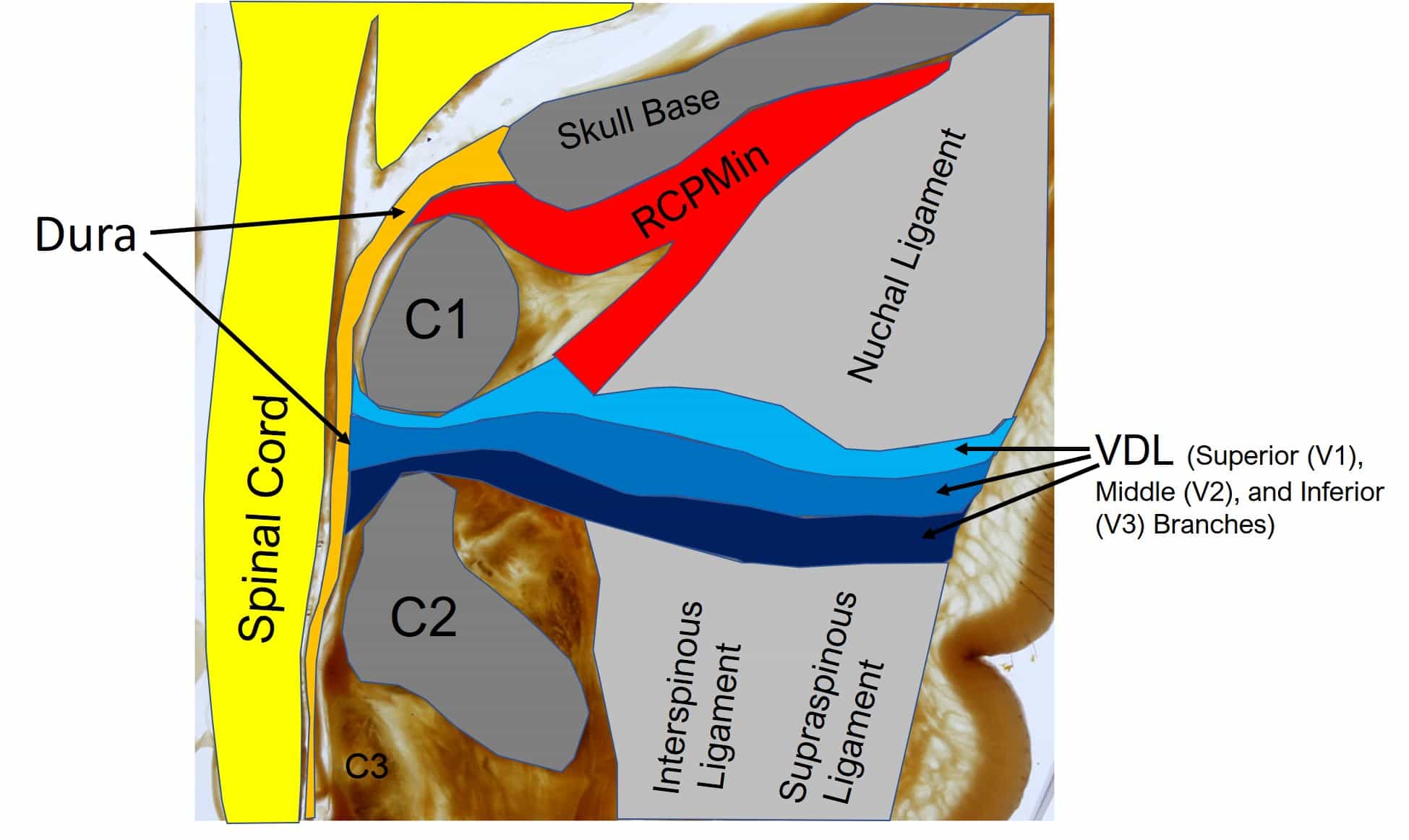

The research study that describes these new structures, which are collectively known as the VDL (ventrodural ligament), is really dense. In fact, even the plastination slices are so complex that someone like me who is a constant student of the anatomy of the upper neck, had a hard time interpreting them. To make it easier, I took one of their slides and illustrated over it to clean it up and harmonize it with what the authors describe:

So here you see the major ligaments of the posterior spine (gray), which up top connect to the skull and are called the nuchal ligaments and lower down in the neck are called the supraspinous/interspinous (SS/IS) ligaments. These critical structures are what hold the bones together when you look down.

In the multi-colored image of the new VDL ligament above, first, realize that you’re looking at a cross-sectional side view that is slightly off of midline. Next, you see the dura in orange and then the RCPMin muscle (red) connecting into that between the skull base and the C1 vertebra (in dark gray). Next, note the VDL ligament (three shades of blue), which is part of the nuchal and SS/IS ligaments and connects into the dura between C1 and C2. Also, realize that there is actually another ligament between the dura and the VDL (ligamentum flavum), but that definition wasn’t available in this plastination cut.

The three parts of this new ligament (V1, V2, and V3) are important in that they define the anatomical variations seen by the authors. What does that mean? You would think that we’re all built exactly the same, but we’re not. In fact, there are small anatomical variations that everyone has, and this ligament is no exception. For example, in some people, they noted that one of these parts was thicker than in others. In addition, the subparts of the VDL also varied in where they connected into the nuchal ligament.

Also, note that the RCPMin muscle seems to connect into the VDL ligament complex. The authors also discussed how the muscles of the upper neck (suboccipital) likely impact the tension on the VDL ligament. Finally, the authors speculate that the muscles and ligaments are set up this way to carefully control the shape of the dura as the head moves on the neck.

What Does This All Mean for CCJ Instability Patients?

As I discussed above, for CCJ instability patients, the upper neck bones move around too much due to damaged ligaments. While we know that extra motion in joints leads to arthritis and that this can also yank on muscles/tendons and local nerves, what we didn’t know was that all of this can also yank directly on the dura, leading to headaches. In addition, the shape of the dura helps to control the motion of the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord (CSF), and this flow of fluid acts as one of the waste and heat disposal systems of the brain. Hence, it’s possible that extra traction forces on the dura at these spots may change that carefully managed flow of CSF.

Are There Solutions?

A common treatment that CCJ instability patients can try is specific upper cervical chiropractic adjustments. These often help many patients. Other types of therapy can also involve restoring the normal curve in the neck. Finally, traditional neck strengthening in this patient population often fails.

One treatment many CCJ instability patients face is surgical fusion. This is where a surgeon bolts together various parts of the upper neck and head. The problem is that now that we know about these connections to the dura, brain, and spinal cord, all of these surgeries would potentially damage these critical links between head, neck, and nervous system. While in some cases that could help headaches, in others, it could make matters worse. In all surgeries of this area, there is likely significant disruption in how the CSF circulates around the brain due to changes in the shape of the dura. Hence, preserving these connections is likely important.

We’ve been perfecting an ultra-precise injection method to place the patient’s own bone marrow concentrate (rich in healing stem cells) into these damaged ligaments. The goal here is to get them to heal and support the head, which would reduce the yanking on these ligaments/muscles and the dura. In addition, the RCPMin muscle and its tendon and the connective tissue of the VDL may well be damaged themselves, so we are now beginning to target these structures. Want to learn more about our new clinical approach for CCJ instability? Watch my video below and check out the new trial announcement.

The upshot? The upper neck anatomy is poorly understood. I know many CCJ instability patients can confirm this by how poorly they get treated by many physicians and specialists. Hopefully, all of this new research can be used to re-educate a generation of physicians who understand what’s wrong and this leads to many more new therapies for patients suffering from upper neck injuries and disease.

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.