ACL Reconstruction Surgery Is a Second Hit to the Cartilage: Time to Rethink Orthopedics?

ACL reconstruction (ACLR) surgery is a sacred cow of modern orthopedic sports medicine. Most surgeons view it as the first major advancement in that specialty beyond the use of the arthroscope itself. However, this has been an awful decade for orthopedic surgical research with study after study showing that common surgeries are ineffective or harmful. Now a newly published study shows that this sacred cow may be causing more harm than good. Let’s dig in.

The ACL and Reconstruction

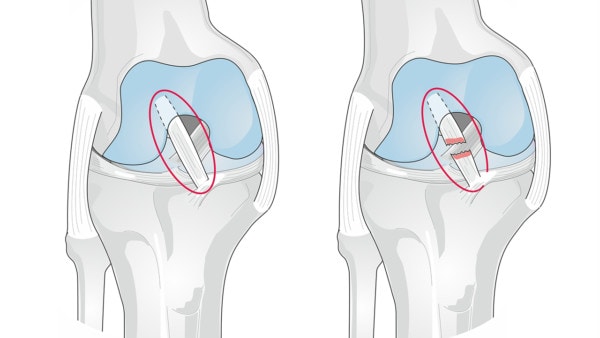

In this illustration, the ACL is circled in red – healthy on the left and injured on the right. Soleil Nordic/Shutterstock

If there was a most famous ligament in your knee, it would be the ACL. This stands for anterior cruciate ligament, which lives inside the joint and helps stabilize it front to back and rotationally. This ligament can be torn in common sports injuries and for the most significantly damaged ACLs, surgical repair is common (1). The problem is that there isn’t much actual repair going on, but instead, a procedure where the surgeon yanks out the damaged ligament, drills holes for a graft, and then strings a tendon in place of the ligament. That surgery is called ACL reconstruction (ACLR).

You’ve likely read about one of your favorite sports heroes injuring his or her ACL and then getting surgery. The athlete is normally out for a season. Because of that exposure and because the procedure has become so common, ACLR has been touted as a modern miracle of orthopedic sports medicine. However, what if the procedure had some serious skeletons in its proverbial closet?

Problems with ACL Surgery

If you look at how surgeons place the tendon that replaces the anterior cruciate ligament, there are problems right off the bat. First, the normal ACL has two bundles that crisscross and help control the rotation of the leg bone, but the ACL graft is only a single tendon. Hence, it has no ability to control that rotation, leaving the knee permanently unstable. Second, the new tendon goes in at a much steeper angle than the original equipment. Hence, it can never provide the same front-back stability with the same efficiency as the original ACL.

However, beyond the obvious, research has identified other problems with the surgery:

- Two-thirds of teens who have ACL reconstruction surgery will end up with knee arthritis by the time they are 30 years old.

- There is a loss of the normal position sense and performance in the knee due to ACL surgery.

- After the surgery on the bad side, there is a higher likelihood of tearing the ACL on the good side.

- Fewer than 1 in 5 athletes are ready to return to sports by 8 months after ACL surgery.

- ACL surgery shortens professional careers.

- Most patients believe that ACL surgery will prevent arthritis, it doesn’t

ACL Surgery and Arthritis

Given that joint instability is a well-researched cause of arthritis you would think that ACL surgery, since it provides some additional stability to the joint, would reduce the risk of getting arthritis. For example, we know that in experimental animal models, if we want to create arthritis, cutting the ACL will cause the knee joint surfaces to move too much and wear down the joint. However, when studying patients who get ACL surgery, they still end up with arthritis (2). Why?

The Second Hit Phenomenon

I often say that much of orthopedic surgery is like a bull in a china shop. Meaning, that surgery is controlled damage to try to fix something. However, when the damage from the surgery is worse than the problem you’re trying to help, why do the surgery? This new data concerns that damage and what’s being called a “second hit” phenomenon. Let’s dig in.

When you injure your knee bad enough to tear the ACL, the cartilage is also usually injured to some extent. In some patients, this can cause a big issue as the repair mechanism is abnormal with far too much inflammation (3). Excessive inflammation + cartilage repair = bad cartilage. Hence, this is one reason why patients likely eventually get arthritis, predicting ACL surgery necessity is a critical question.

However, what if the surgery itself was a second hit to that injured cartilage? I first saw this ACL cartilage data presented while taking part in an orthobiologics think tank at CSU. Basically, a team of researchers measured a cartilage damage chemical inside the joint (CTX-II) both right after the injury and then later after ACL reconstruction. What did they find? That the surgery was as big a hit or bigger to the cartilage as the initial injury! Meaning surgery was killing cartilage cells in the knee because of the inflammation caused by the procedure. How does that happen?

ACL surgery is a huge calamity in the joint. First, fat stem cells that are critical to the health of the knee are often removed because they’re literally in the way of the surgeon visualizing the area (5). Then, big tunnels are drilled inside the joint to hold the ACL tendon graft. Add in hammering and inserting anchors to hold the tendon and it’s a whole lot of invasive human carpentry.

Why Are We Doing this to Most ACL Tears?

We at Regenexx have been successfully treating about 2/3rds of the ACLs that usually get surgery with a precise injection of the patient’s stem cells for years (6,7). This procedure involves the precise injection of the patient’s own stem cells into the ACL. For more information on how that’s done, see my video below:

So rather than exploding an inflammation bomb right beside the knee cartilage a second time by drilling tunnels and playing human carpenter, we use a truly minimally invasive procedure to place healing cells in the ligament.

Time to Rethink ALL of Orthopedics?

Let’s face it, orthopedic surgery in invasive. If we add to that the fact that the research is showing that it doesn’t work, why are we doing this again? To keep hospital OR’s full? It’s time to rethink orthopedics from the ground up and scrap the large swatch of invasive surgeries we know don’t work, and replace them with precise orthobiologic injections. Our bodies will thank us for it!

The upshot? Who knew that cutting out tendons and using drills and anchors wouldn’t be good for the knee? It’s time to get rid of sacred cow surgeries that don’t work and rethink orthopedics to be mostly a precision injection-based specialty. So rather than lots of surgeries with a few blind injections, it becomes few surgeries with lots of precision injections.

_______________________________________________

(1) Marieswaran M, Jain I, Garg B, Sharma V, Kalyanasundaram D. A Review on Biomechanics of Anterior Cruciate Ligament and Materials for Reconstruction. Appl Bionics Biomech. 2018;2018:4657824. Published 2018 May 13. doi:10.1155/2018/4657824

(2) van Meer BL, Oei EH, Meuffels DE, et al. Degenerative Changes in the Knee 2 Years After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Rupture and Related Risk Factors: A Prospective Observational Follow-up Study. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(6):1524-1533. doi:10.1177/0363546516631936

(3) Jacobs CA, Hunt ER, Conley CE, et al. Dysregulated Inflammatory Response Related to Cartilage Degradation after ACL Injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2020;52(3):535-541. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000002161

(4) Hunt ER, Conley CE, Jacobs CA, Ireland ML, Johnson DL, Lattermann C. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Reinitiates an Inflammatory and Chondrodegenerative Process in the Knee Joint [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 19]. J Orthop Res. 2020;10.1002/jor.24783. doi:10.1002/jor.24783

(5) Jiang LF, Fang JH, Wu LD. Role of infrapatellar fat pad in pathological process of knee osteoarthritis: Future applications in treatment. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7(16):2134-2142. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v7.i16.2134

(6) Centeno CJ, Pitts J, Al-Sayegh H, Freeman MD. Anterior cruciate ligament tears treated with percutaneous injection of autologous bone marrow nucleated cells: a case series. J Pain Res. 2015;8:437–447. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26261424

(7) Centeno C, Markle J, Dodson E, et al. Symptomatic anterior cruciate ligament tears treated with percutaneous injection of autologous bone marrow concentrate and platelet products: a non-controlled registry study. J Transl Med. 2018;16(1):246. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30176875

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.