Can We Treat Severe Shoulder Arthritis Through an Injection?

Orthopedic surgeons have taught us that our bodies are just machines, like your car engine, and that when a part breaks down, it needs to be replaced. So they can’t conceptualize how a severely arthritic shoulder joint with no cartilage and huge bone spurs could be treated without replacing the shoulder. However, that’s not what we’ve observed. We’ve treated a good number of patients with severe shoulder arthritis who have been told they desperately need a shoulder replacement. How does that work? I’ll also explain that through a patient’s recent therapeutic experience.

Artemida-psy/Shutterstock

The “Lost Cartilage=Lost Pain” Myth Is Alive and Well

As physicians, we have been taught that lost cartilage and bone spurs seen on an X-ray or MRI is the cause of joint pain. However, according to the two biggest government-funded studies we have, this isn’t true. In fact, when it comes to lost cartilage in the knee, patients who had no or little cartilage didn’t have any more pain than those with cartilage. Given that we have this research, why is everyone so focused on cartilage? Good question.

The Orthopedic Structural Paradigm Is Dying on the Vine

Orthopedic surgeons have taught us all that structure is everything. If you tear a ligament or tendon or have a hole in your cartilage, we need to fix these things with surgery. While sometimes that’s important, there’s also a problem. For example, the idea that we need to surgically “clean up” a joint because it has become arthritic was shown in 2002 to be no more effective than sham surgery. More recently the surgical management of a meniscus tear through getting it cut out surgically (meniscectomy) has also been shown to be ineffective. So why doesn’t all of this work? While there may be some truth to the structural model—for example, if a ligament is torn and causing instability, it may need to be fixed—the idea that what we see on the MRI equals pain, is not accurate.

Can We Treat Severe Shoulder Arthritis Without Joint Replacement Surgery?

A patient I spoke to this week to follow-up on a shoulder treatment is reminiscent of many we’ve seen over the last few years—a guy with severe shoulder arthritis with no cartilage, lost range of motion, large bone spurs, and shredded rotator cuff tendons. Despite all of this, at five months out from his treatment, he reports about 50% improvement. Most of that didn’t start until about four months after his precise stem cell injection. He can now do push-ups again and has returned to the triceps pulls he had stopped. How does this work? Especially since multiple surgeons have told him that he needs a shoulder replacement? It works because the orthopedic structural model is only a little right but mostly wrong.

What’s Right and Wrong About the Orthopedic Structural Model?

If we use this shoulder as an example, we can easily see where the orthopedic structural model works and where it fails. Where it works is the idea that this guy’s large bone spurs prevent motion in the joint. We did little to change his range of motion. Also, without removing those bone spurs, we would never be able to improve his range of motion with an injection.

Where it fails is the idea that this patient’s pain is due to what his joint looks like on MRI. That’s mostly not true. For example, look at a study that demonstrated that the single biggest factor predicting whether a surgical rotator cuff repair worked was not whether the tendon looked better on MRI after the surgery, but in fact the chemical makeup of the shoulder joint! So even if we can’t regrow this guy’s shoulder cartilage, does it matter? So how was he helped? I’d like to posit two mechanisms based on the research in this area and what we’ve observed for the last 12 years. First, we cleaned up the chemical environment of the shoulder by changing it from a toxic witches brew of breakdown to one that can sustain itself. Second, we were likely able to mend small tears in his rotator cuff and provide better mechanical tolerance to load. Given that most of his pain came from those two sources, the pain goes down and the function goes up.

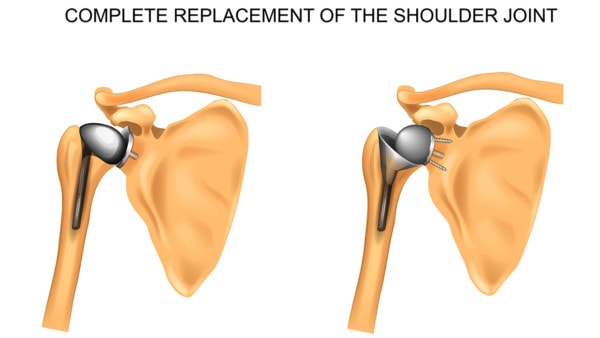

Why Not Just Get It Over with and Replace the Shoulder?

This guy’s shoulder looks trashed on MRI, so why not just get it over with and replace it with a nice, shiny new one? First, amputating his joint and replacing it with metal, plastic, or ceramic is a huge surgery with major side effects at least 100–1,000X more significant than an injection. Second, shoulder-replacement outcomes are some of the worst of all the major joints. So the idea of going back to intense upper-body workouts, like triceps machines and push-ups, is not really tenable with a hunk of metal where his natural shoulder now lives.

The upshot? This patient’s orthopedic surgeon just told him to wait and see if he gets any more relief before considering a replacement surgery. One of the things I love about regenerative medicine is that it causes us to rethink our assumptions. For far too long, we’ve put far too much stock in MRIs and X-rays. In fact, we built an entire surgical specialty called orthopedics on the idea that what the structure looks like is all important, until of course, the data we collect proves that to be mostly a figment of our imagination.

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.