Subchondroplasty: Treating Bone Marrow Lesions In The Knee

Medically Reviewed By:

Subchondroplasty is an innovative procedure to treat bone marrow lesions (BMLs) within the knee, which often appear on MRI scans of individuals with knee arthritis. These lesions can contribute to localized pain and accelerate joint degeneration, making them an essential target for treatment alongside cartilage concerns.

Subchondroplasty involves injecting specialized bone cement into weakened areas of the bone. This procedure has generated considerable interest among medical professionals and manufacturers of bone cement. While early cases have shown promising outcomes, results can vary. Recent clinical observations indicate that some patients may experience less favorable responses.

This guide will review subchondroplasty’s potential benefits and risks and discuss how it integrates into the broader spectrum of knee arthritis treatment options.

Understanding Bone Marrow Lesions

BMLs, sometimes called bone marrow edema (BME), appear as bright or dark spots on MRI scans, depending on the imaging sequence used. These lesions are commonly observed in patients with knee arthritis and indicate areas of bone swelling or damage. Historically, physicians have given BMLs minimal attention.

However, over the past decade—particularly in the last five years—evidence has highlighted their role in the arthritis process. Unlike cartilage loss or meniscal tears, which may not always produce symptoms, BMLs are often linked to pain.

This association has spurred an increased interest in targeting BMLs to alleviate pain and potentially slow arthritis progression, positioning them as a significant focus within comprehensive knee health management.

What Is Subchondroplasty?

Subchondroplasty is a procedure designed to treat BMLs in the knee by stabilizing weakened bone areas. Using imaging guidance, physicians inject a specialized bone substitute material, commonly called bone cement, directly into the affected bone area. This material fills the lesion and hardens within the bone, providing structural support and potentially reducing pain.

By stabilizing weakened bone, subchondroplasty aims to alleviate pain associated with BMLs and may help slow further joint degeneration related to arthritis. This targeted approach represents an option for addressing underlying bone issues that contribute to knee pain in patients with BMLs.

What Is Bone Cement?

Bone cement is an injectable paste that hardens within the body, temporarily stabilizing weakened bone areas. Ideally, this cement is gradually broken down and replaced by new bone tissue over time. Different types of bone cement are available, each with properties suited to specific medical applications.

One common type, polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), is chemically similar to plexiglass; however, PMMA generates heat (an exothermic reaction) as it hardens, possibly posing a risk to surrounding cells.

Calcium phosphate cement is typically preferred for treating BMLs. Unlike PMMA, calcium phosphate cement does not produce heat during setting (an endothermic process), reducing the potential for tissue damage.

Additionally, calcium phosphate closely resembles the mineral composition of natural bone, possibly enabling it to integrate more seamlessly into the bone structure and better support the healing process.

Health Conditions Suitable For Subchondroplasty

Subchondroplasty is particularly suited for treating certain knee conditions where underlying bone issues are central to pain and joint instability. Unlike more generalized arthritis treatments, subchondroplasty focuses on specific areas of weakened or damaged bone that often contribute to chronic knee pain and reduced mobility.

This targeted approach can provide relief by reinforcing and stabilizing these compromised bone areas, making it a potential option for several structural knee conditions.

Below are some primary conditions that may benefit from this procedure:

- Subchondral Bone Defects – Weakened bone beneath the cartilage layer can be a source of pain. Subchondroplasty is designed to reinforce these areas, with the goal of enhancing structural support and addressing localized pain.

- Cartilage Loss With Underlying Bone Damage – When cartilage wears down, bone stress and lesions may increase. Subchondroplasty addresses bone loss by filling these defects, which may reduce pain and improve joint stability.

- Knee Pain Due To Localized Bone Weakness – Localized bone weakness can contribute to knee pain. Subchondroplasty targets and stabilizes these weakened areas, potentially improving pain and knee function.

- Osteonecrosis (Avascular Necrosis): Osteonecrosis, also known as avascular necrosis, occurs when blood flow to a bone is reduced, leading to tissue death. This may cause pain, joint stiffness, and potential bone collapse, often affecting weight-bearing joints such as the hip, knee, or shoulder. Read More About Osteonecrosis.

Considerations For Bone Cement Use In Subchondroplasty

Bone cement is sometimes used in subchondroplasty to stabilize weakened or damaged bone, particularly in areas affected by bone marrow lesions (BMLs). While it can provide structural support and potential pain relief, there are several important considerations for its use:

Types of Bone Cement And Safety

Different formulations of bone cement are available, each with varying viscosity, curing times, and mechanical properties. Selecting the appropriate type is essential for maximizing effectiveness and minimizing complications.

Patient Selection

Not every patient is a candidate for bone cement treatment. Physicians evaluate factors such as lesion size, bone quality, overall joint health, and previous procedures to determine suitability. Patients with severe cartilage loss or extensive bone damage may require alternative therapies.

Potential Risks

Improper placement or technique can lead to complications, including cement leakage into the joint space, local inflammation, or failure to integrate with the surrounding bone. Rarely, incorrect application may accelerate joint deterioration rather than stabilize it.

Surgeon Experience and Technique

The skill and experience of the treating physician play a critical role in outcomes. Precision in targeting BMLs, correct injection technique, and careful imaging guidance are all necessary to reduce risk and optimize results.

Cautionary Case Example

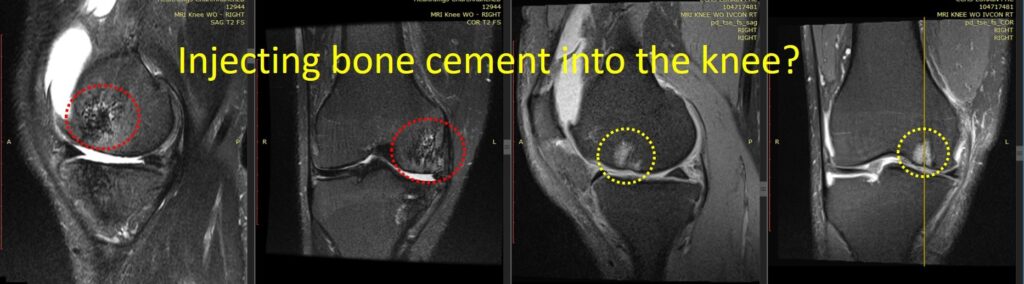

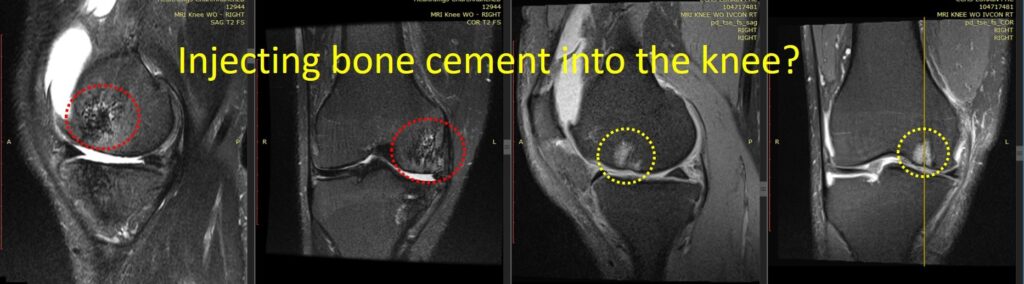

A patient pursued stem cell treatment for knee arthritis after complications from a prior subchondroplasty. During an initial bone cement injection into BMLs, the surgeon, performing the procedure for the first time, unintentionally worsened the condition.

Follow-up MRI images revealed structural changes: the original BMLs (highlighted in yellow dashed circles) appeared as bright spots on imaging, while post-procedure images (red dashed circles) showed areas of bone deterioration, with gaps and holes replacing healthy bone. Over nine months, significant cartilage loss also occurred.

This case underscores that while bone cement can be beneficial when used correctly, improper application can accelerate joint damage rather than provide stabilization. Careful patient selection, proper cement type, and experienced technique are essential for safe and effective subchondroplasty.

Alternative Treatment Options For Bone Marrow Lesions

For individuals exploring non-surgical approaches to managing BMLs and knee discomfort, physicians in the licensed Regenexx network offer interventional orthobiologic procedures that may be considered as part of a personalized care plan.

Bone marrow concentrate (BMC) procedures are one approach that involves using a patient’s own biologics, processed using Regenexx lab techniques. Research has investigated the use of BMC in orthopedic applications, showing promising results in subchondral bone lesions, though further studies continue to evaluate its long-term role.

Physicians in the licensed Regenexx network may recommend BMC injections as part of a broader joint care strategy. Patients who have had this treatment have reported improvements in knee function and discomfort levels. This customized approach is designed to support joint health and mobility while exploring less invasive options for managing knee conditions.

Find Non-Surgical Options To Support Knee Function

Advanced knee care focuses on individualized approaches that align with a patient’s specific needs. While bone cement has been traditionally used to stabilize weakened bone, some individuals may explore non-surgical approaches as part of their overall care plan.

Physicians in the licensed Regenexx network offer interventional orthobiologic procedures that may be considered to support joint function and mobility. By focusing on personalized, image-guided techniques, these approaches aim to help patients manage discomfort and explore options that fit their treatment goals.

For individuals seeking less invasive options to help support knee function, consulting with a physician in the licensed Regenexx network can provide insights and determine whether a non-surgical approach may be helpful for their condition.

Am I A Candidate?

To talk one-on-one with one of our team members about how the Regenexx approach may be able to help your orthopedic pain or injury, please complete the form below and we will be in touch with you within the next business day.

Medically Reviewed By: