Drug Development vs. Physician Innovation: A Primer for Academics and Journalists

One of the things that really confuses bench scientists and science journalists is the stark difference between how drugs and medical procedures are developed and tested. These groups tend to conflate the two, which is like comparing apples and oranges and then being upset that a Vermont McIntosh is not like a California Tangerine. Let me explain.

The Problem

The media can’t seem to differentiate between the proper use of physician innovation and the stem cell charlatanism which is rampant in the stem cell wild west. I can’t blame them, their opinions have generally been driven by bench scientists who aren’t clinicians. Those scientists only know one medical development pathway which I’ll call “Lab Bench Innovation”. They have no idea that there is another one, which I’ll call “Physician Innovation”.

Drug Development via Lab Bench

Drugs are usually developed from a ground-up approach. Meaning a compound is discovered in a lab and then tested in-vitro. This means that it’s exposed to cells in the lab. If that looks promising, it’s next tested on small animals like rats or mice. Then it’s usually tested on larger animals and if it looks safe and effective, it then goes through a rigorous FDA approval process. This is a phase 1 safety trial in a small group of patients which is followed by larger randomized controlled trials. If it passes that test, it’s granted FDA approval.

Like everything, this process has its positives and negatives. A positive is that it is very focused on placing safety first and it’s extremely rigorous. The problem is that it’s also ridiculously expensive and few drugs make it from the lab to the bedside. It also drives behaviors which can harm select patient populations. Meaning that in order to recoup the expense, drug companies focus on big markets. They also design clinical trials with strict inclusion and exclusion criteria that don’t reflect the real world of patients being treated. They do this to maximize the chances of a successful trial.

Physician Innovation

While many academics and science journalists are familiar with drug development (Lab Bench Innovation), they have little practical knowledge about how medical care itself is developed. So for instance, they have no idea that if they’re in a car crash and have to go to the ER for life-saving trauma care, that these techniques were developed by doctors trying different things to save GIs in the Korean and Vietnam Wars. They were specifically NOT developed in the lab at some university.

So how is new medical care actually developed? Here are some examples:

- A doctor is taught to perform a procedure a certain way and decides through experience to modify it because he or she believes this will yield a better result.

- A doctor uses a medication approved for disease X on disease Y. This is called “off-label use”.

- A doctor takes a tissue from a patient that is usually used to treat one set of conditions and uses it to treat other conditions.

The area where academics and journalists get confused is that they view all of the above through the lens of drug development. Viewed that way, these physician innovation pathways can be made to look irresponsible. After all, where’s the lab and animal testing? How about the FDA phase 1, 2, and 3 stuff?

Research in Medical Innovation

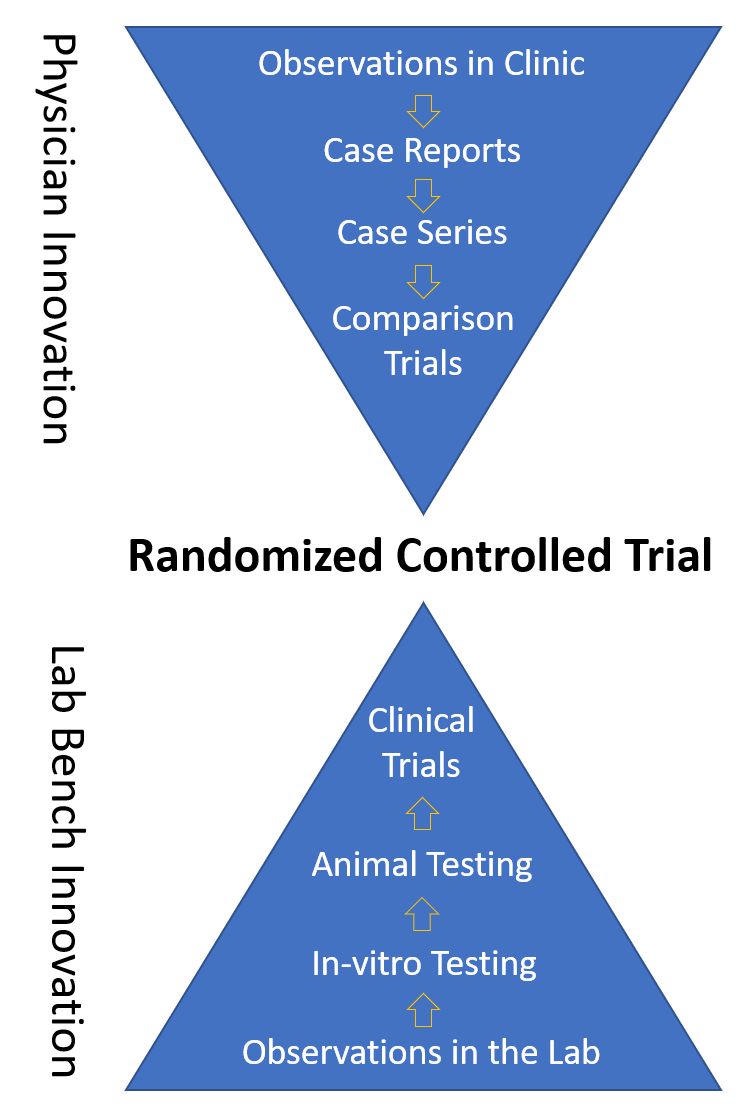

If drug development is a bottom-up approach, physician-driven innovation is very much top down. Meaning that medical innovation often starts with a doctor making changes to improve one person’s medical outcome. If that works, then the doctor tries this approach in more patients. If it still works, then a case report is published. Then more outcomes are tracked and a case series is created. Next up is a comparison trial testing procedure A versus B. The final step for the doctor would be to publish a randomized controlled trial.

Up until the randomized controlled trials, the doctor is simply practicing medicine using both the new and the old method. In fact, this leeway in the ability to ad lib a treatment so that it better fits the patient or to create new treatments is why physician training is the most extensive of any health care practitioner. Physicians are trained to do this, which is in society’s best interest.

Ending Up in the Same Place

Despite starting in different places, the drug development pathway and the physician innovation pathway end up in the same place. One is focused on moving breakthrough lab discoveries, which are dangerous until proven otherwise, into patients. The other on taking smaller iterative steps in evolving or perfecting existing medical care. Both end up in a randomized controlled trial.

The Problems with Holding Medical Procedure Advancements to Drug Development Standards

Medical care has advanced to where it is because of smart physicians who try new things that work better than the old way. To the extent that these changes are low risk, this makes sense. Otherwise, medical innovation, if required to get a drug approval or go back to the university lab every time it happened, would grind to a screeching halt. Hence, we as a society have a need to support physician innovation. In fact, one day, for most of us, our lives will literally depend on this type of innovation.

Academic Documents that Codify Physician Innovation

What many academics and science journalists don’t understand is that the discussion of physician innovation isn’t new or novel. In fact, this has been codified in many international documents including the Belmont Report and the Declaration of Helsinki.

The Belmont Report

Belmont was the seminal U.S. document off which much of our current research bioethics scheme is based. It was a large group of academics convened in the 70s to decide how to keep patients involved in research safe. It also has quite a bit to say about how the practice of medicine, innovation, and research dovetail:

“When a clinician departs in a significant way from standard or accepted practice, the innovation does not, in and of itself, constitute research. The fact that a procedure is “experimental,” in the sense of new, untested or different, does not automatically place it in the category of research. Radically new procedures of this description should, however, be made the object of formal research at an early stage in order to determine whether they are safe and effective.”

“Research and practice may be carried on together when research is designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a therapy.”

So Belmont clearly understands that medicine is often advanced by physicians trying new things and that if radically new things are used, then that should be made the subject of a research project.

Declaration of Helsinki

The Declaration of Helsinki is in many ways an international equivalent of the Belmont report. This is what it has to say about physician innovation:

“In the treatment of an individual patient, where proven interventions do not exist or other known interventions have been ineffective, the physician, after seeking expert advice, with informed consent from the patient or a legally authorised representative, may use an unproven intervention if in the physician’s judgement it offers hope of saving life, re-establishing health or alleviating suffering. This intervention should subsequently be made the object of research, designed to evaluate its safety and efficacy. In all cases, new information must be recorded and, where appropriate, made publicly available.”

Here Helsinki clearly recognizes that physicians can innovate to help any individual patient as long as research follows the innovation. Note that Helsinki defines a pattern for physicians. Treatment first to help a unique patient or patients and then research to back up what the physician believes. Note that neither document states that randomized controlled trials are needed before medical care can occur. That places these documents in direct conflict with the statement of academics and journalists who believe that when it comes to orthobiologics, we need randomized controlled trials BEFORE care can happen.

Responsible vs. Irresponsible Physician Innovation

Not understanding how physician innovation happens and that there are carve-outs for it in several key international bioethics documents, often causes science journalists to write templated stories that can’t differentiate responsible physician innovation from the wild west of stem cells. That story template includes numerous university talking heads who also don’t understand physician innovation, so the baby gets thrown out with the bathwater. So what are the differences?

Responsible Physician Innovation looks like:

- The substance is not classified by FDA as a drug that requires approval but fits squarely into the physician practice of medicine

- Based on the existing research, the innovation is more likely than not to be safe

- All consented patients are tracked in a registry that queries patients for outcomes and complications at set time points

- Research on the procedure is published using the pathways described above

- Based on the data collected, strict candidacy guidelines for who is and who is not a candidate for the therapy are established

Irresponsible Physician Innovation looks like:

- The substance is classified by FDA as a drug that requires clinical trials before use

- There is poor existing research, so the safety of the therapy is completely unknown

- No patient results or complications are tracked in any formal way

- No research is published

- Everyone is a candidate

Testing Examples

Now let’s compare what we do at Regenexx with “stem cells” versus the chiropractic and physician clinics practicing in the wild west. We use bone marrow concentrate (BMC) which fits easily into the 21 CFR 1271.15(b) same surgical procedure exemption. Meaning that using this substance for orthopedics (BMC is derived from bone) to treat arthritis (a disease of bone and cartilage) is the practice of medicine and requires no FDA drug approval. BMC has been used since the 80s and 90s and is the subject of many clinical trials. Hence, deciding to move that use from avascular necrosis of the hip (a bone disease where it has been used since the 90s) to treat knee osteoarthritis is a likely safe innovation. We have always tracked patients in a registry as described. We have published case reports, large case series, comparison trials, and finally, RCTs as described. Based on that data, we use strict candidacy guidelines for who gets the therapy.

Now let’s look at a chiro clinic delivering umbilical cord blood intravenous for anti-aging or even knee arthritis. First, there is no FDA approved use of allogeneic umbilical cord blood intravenous to treat anything other than pediatric cancers. So right off the bat, using it to treat aging or arthritis is the use of an unapproved drug product. There is no pre-existing research that shows that using allogeneic umbilical cord blood in this way will help reduce aging or knee arthritis symptoms. In addition, there is limited data on using the type of commercially available umbilical cord blood in a donor unmatched setting intravenous or intra-articular into knees in adult humans who are otherwise healthy. So safety is unknown. These clinics do not use a registry. They do not publish their results and everyone is a candidate.

The upshot? It’s time for science journalists and the university bench scientists to get educated about how physicians have been innovating responsibly for centuries. While major bioethics documents clearly understand this form of innovation, it seems to be invisible to these influential media actors. That needs to change. In addition, there are distinct differences between responsible and irresponsible innovation.

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.