Manipulating the Data to Get What You Want: The PRP Systematic Review by O’Dowd

In medicine, you can often break those that publish research into two categories. There are those who invest a huge amount of time and resources to study a clinical concept, whether in the lab or clinic, and then there are the “reviewers.” Today we’ll go over this duality by diving into how easy it is for reviewers to manipulate the clinical research published by others to get the answer they want. So while a meta-analysis or systematic review may look very legit, it often begins with a predetermined answer and then backs into setting the filters to get that answer. I’ll tell that story through a recently published PRP systematic review by O’Dowd.

Some Quick Definitions

The research types I’m referring to when I use the term “review” are:

- Systematic Reviews-Research that looks at the outcome of various studies to try and draw an overall conclusion about the efficacy of a treatment.

- Meta-analyses-Research that amalgamates the data from many studies on a topic and then re-analyzes it to conclude about the efficacy of a treatment.

This blog will focus on a systematic review, but the same concepts also apply to meta-analyses.

Dialing In the Research Knobs and Filters

There are often hundreds to thousands of studies published on a specific topic, and since we’re not AIs but humans, it’s worth reducing that number to some manageable amount of research to be reviewed. Hence, those performing systematic reviews and meta-analyses often place filters to reduce that number. Let’s dig in here a bit.

Some filters are reasonable, and the most common is only to include Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs). This means that you’re only reviewing the highest quality research out there. That one step often reduces the number from hundreds to dozens of studies.

However, we often see reviews that include other filters. Some of those could also be very reasonable. For example, if the study includes platelet-rich plasma (PRP), the study should have used PRP that meets the minimum definition for PRP concentration which is 2X. Or maybe a filter for specific diagnoses if the treatment under review is PRP.

However, some filters are clearly used to get the desired review conclusion. Let’s dive into one such study that was just published on PRP.

A New Systematic Review on PRP by O’Dowd

A new systematic review was recently published on PRP in the Orthopedic Journal of Sports Medicine by O’Dowd (1). That paper used the following filters:

Inclusion:

- Compares PRP with a non-PRP/placebo in participants >18 years

- Musculoskeletal soft tissue injury

Exclusion:

- Non–soft tissue injuries

- Research published in journals with an impact factor <3.5

The problems with the methodology of this systematic review begin right out of the gate. While the filter of comparing treatment A (PRP) to Treatment B (placebo) would be very reasonable, there’s an addition here that completely mixes up the pot. Note the term “non-PRP.” That means that studies that compared PRP to a placebo would be included with studies that compared PRP to a steroid or exercise. Those are different studies. The first is a placebo trial, and the second is against a common treatment. So while that might make sense for a casual review of what’s out there, it isn’t very focused for a systematic review.

The next confusing filter is “Musculoskeletal soft tissue injury.” To better define that, the paper says that the author searched for the terms:

- soft tissue injury

- muscle injuries

- tendinopathy

- ligament injuries

- musculoskeletal injuries

In the PRP research, that means pulling up studies on two main areas: tendinopathy and muscle-tendon injuries.

However, the most bizarre filter here, and one I haven’t seen very often, is the fact that the “impact factor” of the journal must be 3.5 or above. This is a rating system of journals that really says little about the quality of the underlying research. Hence, why include this metric? As you’ll see below, IMHO, it was included to exclude high-quality research that didn’t fit with the predetermined narrative of this paper.

Focusing on Tendinopathy

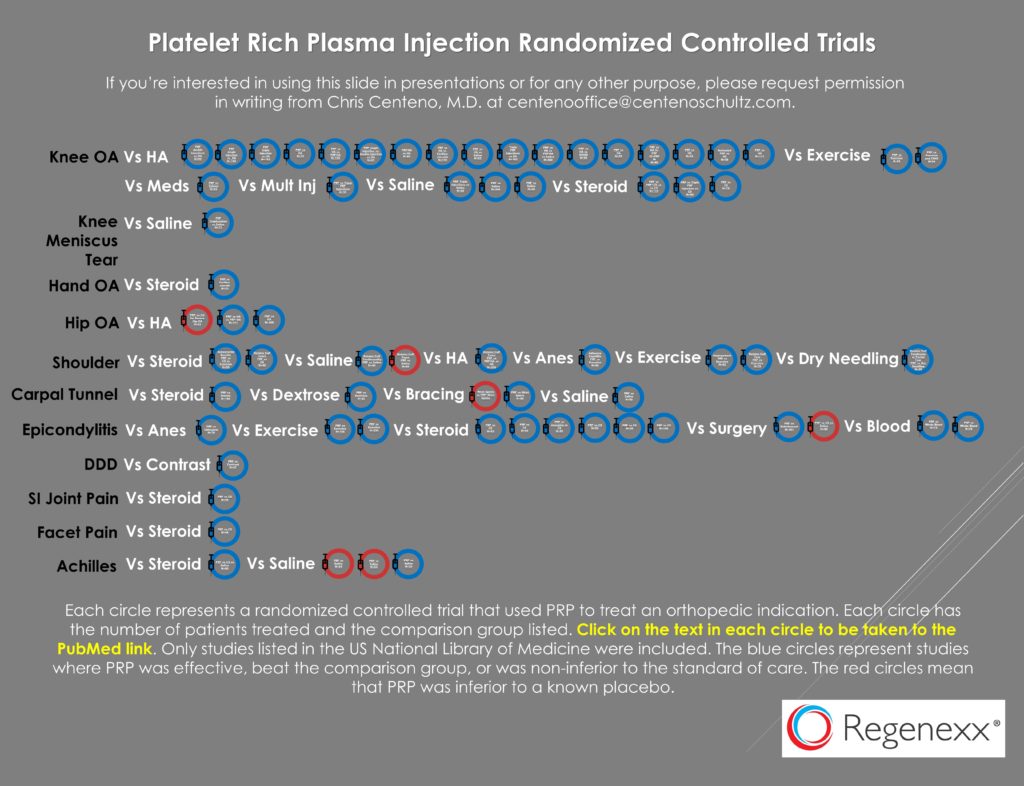

The paper includes all sorts of areas where the PRP research is pretty nascent as of the 2021 cut-off, but it also includes at least one area where it’s more mature, which is tendinopathy. That diagnosis category includes lateral epicondylitis or tennis elbow. This is an area where I have searched Pubmed for listed RCTs, and as of 2019, I had identified thirteen:

So how many RCTs were identified by this review paper as of 2021? Two. What happened to the other eleven studies? They were filtered out. The two that were left were negative studies. The first study noted, published in 2020 by Linnanmäki et al., didn’t actually use PRP (2). Instead, it used the Arthrex ACP system, which produces a 1.3X platelet concentrate which doesn’t meet the minimal 2X definition of PRP established by Marx (3,4). The second study by Montalvan also never used PRP because it also used the 1.3X Arthrex ACP system (5).

So, what types of studies on lateral epicondylitis were filtered out? For example, not included was a positive and massive multi-site RCT including many more patients than the above two fake PRP studies (230 patients) that was published by Mishra et al. (6). Why wasn’t this study included? It was published in the American Journal of Sports Medicine with an impact factor of 6, well above the 3.5 cut-off. In fact, AJSM is the highest-rated orthopedic journal. However, Mishra et al. was published just one month prior to the random cut-off date listed for this study of March 2014. Given that any author searching this literature would have come across the Mishra paper, and bizarrely it just missed inclusion, IMHO, this exclusion, more likely than not, was purposeful.

Achilles Tendinopathy

For the diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy, we also find problems with this review. For example, the author writes:

“Eight studies investigated the nonsurgical management of tendinopathies using PRP.”

The author then states that four of the eight were about Achilles tendinopathy. So let’s dive into those four included studies. The first study referenced as a citation for that statement was Boesen et al. (7). That study was NOT about tendinopathy as claimed, but instead about acute Achilles tendon ruptures. The second study, also by Boesen, did treat tendinopathy but didn’t use PRP as it used the same 1.3X ACP as the studies highlighted above (8). The third study was by Kearny et al., which I have previously blogged on because it injected low-concentration PRP that did meet the criteria of being classified as PRP but that instead injected far more leukocytes than platelets (9). However, at least this study qualifies within what the author filtered. Finally, the fourth study by Kroh et al. was tiny at 24 patients, with 12 patients in each group, but at least it seemed to use PRP to treat Achilles tendinopathy (10).

Hence in this category, we have one mislabeled study, one that didn’t use PRP, one that did use PRP with more leukocytes than platelets, and one that only treated 12 patients with PRP. Not a ringing endorsement for any data where a conclusion could be drawn. Where are the two studies listed above in my 2019 infographic that showed positive results?

Comments on this Review

The term for this systematic review is “cherry-picking.” In this case, adjusting the inclusion and exclusion criteria to include more negative than positive RCTs. In addition, the author seems oblivious to the concept that there is a definition for what is and is not PRP, with the minimum being at least 2X concentrated. Finally, many of the areas included are in the earliest stages of research, like the treatment of the meniscus with PRP. However, even the positive trial result reported by Kaminski et al. in that area is downplayed (11).

This Takes Time

I don’t know how many of these review studies or clinical trials are designed to show a negative result I have performed an in-depth review to date. Likely more than a dozen. They all take lots of time. For example, even this partial review to get to the conclusion of cherry picking by O’Dowd took about 4-5 hours to complete. However, like the other studies I have highlighted, it’s unlikely that anyone who wants to get rid of PRP will ever take the time to dig into the details of this poorly done systematic review.

The upshot? I hope you learned how to create a systematic review that concludes whatever you want. You adjust your filters to exclude anything that doesn’t fit the narrative. In the case of the O’Dowd systematic review on PRP, you also include many papers that never used PRP.

___________________________________________________________________________________

(1) O’Dowd A. Update on the Use of Platelet-Rich Plasma Injections in the Management of Musculoskeletal Injuries: A Systematic Review of Studies From 2014 to 2021. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2022;10(12). doi:10.1177/23259671221140888

(2) Linnanmäki L, Kanto K, Karjalainen T, Leppänen O, Lehtinen J. Platelet-rich plasma or autologous blood do not reduce pain or improve function in patients with lateral epicondylitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478(8):1892–1900. doi:10.1097/CORR.0000000000001185

(3) Magalon J, Bausset O, Serratrice N, Giraudo L, Aboudou H, Veran J, Magalon G, Dignat-Georges F, Sabatier F. Characterization and comparison of 5 platelet-rich plasma preparations in a single-donor model. Arthroscopy. 2014 May;30(5):629-38. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.02.020. PMID: 24725317.

(4) Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma: evidence to support its use. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004 Apr;62(4):489-96. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.12.003. PMID: 15085519.

(5) Montalvan B, Le Goux P, Klouche S, Borgel D, Hardy P, Breban M. Inefficacy of ultrasound-guided local injections of autologous conditioned plasma for recent epicondylitis: results of a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial with one-year follow-up. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(2):279–285.

(6) Mishra AK, Skrepnik NV, Edwards SG, Jones GL, Sampson S, Vermillion DA, Ramsey ML, Karli DC, Rettig AC. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma for chronic tennis elbow: a double-blind, prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled trial of 230 patients. Am J Sports Med. 2014 Feb;42(2):463-71. doi: 10.1177/0363546513494359. Epub 2013 Jul 3. PMID: 23825183.

(7) Boesen AP, Boesen MI, Hansen R, Barfod KW, Lenskjold A, Malliaras P, Langberg H. Effect of Platelet-Rich Plasma on Nonsurgically Treated Acute Achilles Tendon Ruptures: A Randomized, Double-Blinded Prospective Study. Am J Sports Med. 2020 Jul;48(9):2268-2276. doi: 10.1177/0363546520922541. Epub 2020 Jun 2. PMID: 32485112.

(8) Boesen AP, Hansen R, Boesen MI, Malliaras P, Langberg H. Effect of high-volume injection, platelet-rich plasma, and sham treatment in chronic midportion Achilles tendinopathy: a randomized double-blinded prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(9):2043. doi:10.1177/0363546517702862

(9) Kearney RS, Ji C, Warwick J, et al. Effect of platelet-rich plasma injection vs sham injection on tendon dysfunction in patients with chronic midportion Achilles tendinopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326(2):137–144. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.6986

(10) Krogh TP, Ellingsen T, Christensen R, Jensen P, Fredberg U. Ultrasound-Guided Injection Therapy of Achilles Tendinopathy With Platelet-Rich Plasma or Saline: A Randomized, Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Am J Sports Med. 2016 Aug;44(8):1990-7. doi: 10.1177/0363546516647958. Epub 2016 Jun 2. PMID: 27257167.

(11) Kaminski R, Maksymowicz-Wleklik M, Kulinski K, Kozar-Kaminska K, Dabrowska-Thing A, Pomianowski S.Short-term outcomes of percutaneous trephination with a platelet rich plasma intrameniscal injection for the repair of degenerative meniscal lesions: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(4):856. doi:10.3390/ijms20040856

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.