The Great California Worker’s Comp PRP Magic Trick

Worker’s comp is one of those insurance company types that, more often than not, has been covering PRP. However, a colleague recently sent a “Guideline” issued by the California workers comp that removes PRP coverage. Today, I want to dive deeply into this document and explain why it’s more of a magic trick than a well-researched systematic review.

Magic 101

Magic is all about distracting people. You do something over here to distract, then perform the trick when they’re not paying attention. Let’s dive into how this California worker’s comp guideline trick is done.

The State of California Worker’s Comp and PRP

My colleague, who has been getting reimbursed for PRP in California worker’s comp patients for years, tells me that before the new guideline, the coverage looked like this:

-2nd line therapy only

-Age over 50

-For patellar tendinopathy

-For early mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis (OA)

It’s not ideal, but not bad. Now, California worker’s comp uses ODG (Official Disability Guidelines) to supply its recommendations for PRP, which looks like a guideline product offered by what used to be known as Millman but is now known as MCG (Millman Care Guidelines).

A Deep Dive into ODGs PRP Guideline

ODG issued a non-coverage guideline for PRP for any orthopedic or musculoskeletal condition. This is a big document with many references, so today, I will review the evidence provided to reach a non-coverage decision on knee osteoarthritis. This blog will focus on PRP injections.

Below, you’ll see the ODG guideline in italics, followed by my comments. The ODG references are included with their original citation numbers and the citation number I have used for this document to keep everything organized. Realize that this guideline is not focused on the many specific diagnoses of the knee, like osteoarthritis, tendinopathy, ACL tear, etc., but instead on the body part. That makes this guideline a bit of a mess in that only one small part even mentions knee OA.

Knee pain or injury (not recommended):

A systematic review of randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials identified 19 studies (with a total of 1088 patients) evaluating the efficacy of PRP for the treatment of rotator cuff tear repair, shoulder impingement syndrome surgery, elbow epicondylitis, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, patellar tendinopathy, and Achilles tendinopathy and rupture repair; the authors found that the evidence was insufficient to support the use of PRP for musculoskeletal soft tissue injuries. (1)

This statement doesn’t cover knee osteoarthritis; it is a bizarre systematic review covering seven diagnoses. A systematic review takes one intervention and one diagnosis and comprehensively reviews the high-level published literature on that topic. This one was also published in 2013/2014 before most of the existing PRP data was published, which could explain why it includes so many diagnoses, as not much was known about PRP at the time. However, this also means that including it in a coverage decision in 2024 on the knee is ridiculous. For example, as of 2023, there were more than 100+ RCTs (randomized controlled trials) on PRP, not the 17 that this review identified.

Of the knee studies included, most were about surgical ACL reconstruction and NOT related to an interventional orthobiologics application, which is the focus of today’s blog. Two focused on reducing graft donor site morbidity, and four focused on ACL reconstruction. The only injection-based study was in the ultrasound-guided treatment of patellar tendinopathy versus dry needling (i.e., not knee osteoarthritis).

A systematic review of 58 studies concluded that there is insufficient evidence to determine if PRP is useful for the treatment of upper limb (epicondylitis, rotator cuff) and lower limb (patellar, Achilles, plantar fasciopathy) tendinopathies. (36-my reference 4)

This systematic review was published in 2015, again before much of the existing literature available in 2024 was published. Are you beginning to see a trend here? Why use any older systematic reviews before 2023 or 2024? They would only contain a fraction of the literature available today for review.

This systematic review claims to include 58 studies, but only 6 were RCTs on the lower limb. Again, this review doesn’t focus on any one medical condition. No studies have been reviewed here that involve knee osteoarthritis. Instead, the focus is on injections for patellar tendinopathy.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials (including 765 patients) evaluated the efficacy of anterior cruciate reconstruction with or without intraoperative PRP augmentation and found, at mean 18-month follow-up, that there was no difference in improvement between treatment groups. The findings were limited by small study populations and interstudy heterogeneity, including reconstruction protocols, outcome measures, and follow-up time; further larger, well-designed randomized controlled trials were recommended. (39 my reference 5) For anterior cruciate ligament repair, a systematic review of 11 randomized controlled trials (516 patients) found that, although PRP appears to enhance graft maturation and bone-ligament interface healing, there is insufficient evidence that clinical outcomes (as measured by symptom, pain, and function scores) are improved. The authors noted that the studies had considerable heterogeneity with regard to such variables as volume and concentration of PRP, location of injection, surgical technique, and rehabilitation protocols. (40 my reference 6)

Again, the focus of the above studies is surgical ACL reconstruction.

For patellar tendinopathy, a systematic review of 11 studies (including 2 randomized controlled trials) found that, although all observational studies showed a significant improvement in pain and function after PRP injection, the outcomes of the comparative studies were inconsistent and, on that basis, the superiority of PRP over control could not be conclusively demonstrated. Additional high-quality randomized controlled trials were recommended to determine the efficacy of alternative treatments for patellar tendinopathy as well as to identify those subgroups of patients who would benefit most from treatment. (41 my reference 7)

This is, again, a 2015 review article and not on topic for this blog.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials (1069 patients) comparing the efficacy of PRP, hyaluronic acid, and placebo (saline) for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis found, at 12-month follow-up, that PRP was associated with improved pain and function scores. However, the authors noted study limitations, including varied PRP preparations, varied injection frequency and volume of both agents, substantial patient heterogeneity, and that the majority of the conclusions were based upon only 2-3 studies. (42 my reference 8)

Yet again, this is an old 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis. The results were favorable for knee OA, but since 2015, the latest papers included in this review, many more PRP papers have been published on PRP and knee OA. Hence, this review is not appropriate for inclusion in a 2024 guideline.

A triple-blinded randomized controlled trial of 288 patients with symptomatic medial knee osteoarthritis compared intra-articular PRP treatment with saline and found, at 12-month follow-up, no difference in average knee pain scores and percentage change in medial tibial cartilage volume (as measured by 11-point pain scale and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], respectively) between groups. Findings were limited by potential lack of generalizability to patients with more severe osteoarthritis or treated with different PRP preparations. (43 my reference 9)

So, while our fearless ODG worker’s comp guideline authors have included reviews containing 9-15-year-old PRP data, they included the recent Benell study, which didn’t actually use PRP but plasma with the same amount of platelets as whole blood. Interestingly, they excluded an RCT from 2022 by Chu that included twice as many patients as the Bennell study, which showed superiority over placebo and actually used real PRP (10).

A specialty society practice guideline strongly recommends against PRP for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. (9 my reference 11) (EG 2) Another specialty society practice guideline gives a limited recommendation for the use of PRP to reduce pain and improve function in patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee, based on low-level evidence from heterogeneous studies with mixed results. (44 my reference 12)

This interesting approach includes two opposing specialty guidelines, one from Rheumatology recommending against PRP and the other from Orthopedic surgery recommending it in a limited fashion. The American College of Rheumatology guidelines recommend types of care that we know don’t work and are bad for knee cartilage, like corticosteroid injections, while PRP is not recommended. So, what was the recommendation against PRP based on? Nothing. This is NOT a literature review and recommendations but a voting panel for consensus. This recommendation document doesn’t include a single PRP scientific reference.

How about the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons guideline? The wrong one was used, with the authors referencing the 2021 document in 2023 when a 2022 version is available. Let’s look at the correct guideline (v3 2022). There is still a limited recommendation for the use of PRP, with the authors stating that practitioners should be aware of the emerging evidence (as referenced above). Again, this is a consensus guideline with no analysis of the PRP literature.

Given that few medical society guidelines have done any review of the PRP literature let’s look at the top 10 US medical schools (according to US News and World Report) to see if they offer PRP as a treatment:

- Harvard-Yes

- Johns Hopkins-Yes

- University of Pennsylvania-Yes

- Columbia-Yes

- Duke-Yes

- Stanford-Yes

- UCSF-Yes

- Vanderbilt University-Yes

- Washington University-Yes

- Cornell University-Yes

- NYU-Yes

- Yale-Yes

So, 10/10 of the top 10 medical schools in the US offer PRP. What do the professors at these medical schools know that ODG doesn’t? How can these medical schools offer PRP when ODG claims it doesn’t work?

Recent Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Not Included

So, what positive reviews on using PRP to treat knee OA exist as of this writing that could be included in the ODG guidelines tomorrow?

- A systematic review, which ties a higher dose of PRP to positive clinical outcomes (14)

- The ESSKA-ORBIT consensus, which is a literature review performed by the largest European sports medicine group, recommends PRP use for knee OA (18)

- A recent summary of the Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews of PRP used to treat knee OA concludes that PRP is effective (19)

These are all 2024 papers, which is what one would want for a guideline being used in 2024.

How Bad is the ODG Guideline?

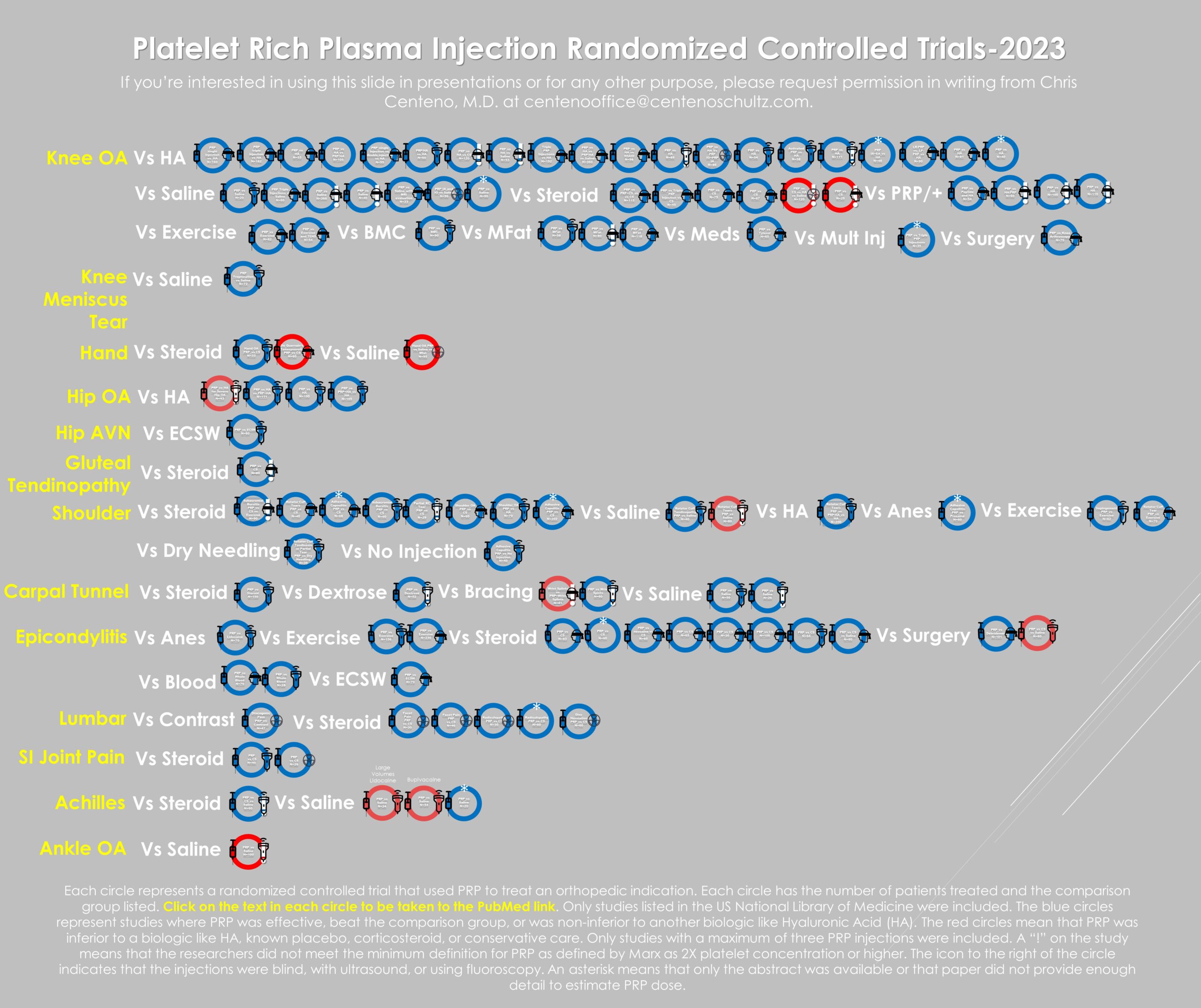

Below, I have indexed more than 100 RCTs as of last year that were published on PRP:

The red circles are the trial failures, representing a small percentage of the overall studies. As of that date, there were 46 RCTs in knee OA, with only two being negative for a successful trial rate of 95%. The two negative trials both used “fake PRP,” meaning kits unable to produce at least a 2X platelet concentration, just like the Benell et al. paper referenced by ODG.

PRP Dose is Key

The guidelines above reference papers that discuss the problem of heterogeneity in PRP preparations. This means that unlike studying a drug, PRP prep A may be different from PRP prep B. This has always been a problem, but that issue is now being sorted out. First, there were simple classification systems, such as the differences between leukocyte-rich and leukocyte-poor PRP preparations (13). Then, publications on how the dose of PRP is related to cellular repair activity and clinical outcomes were published (14-17). The latest meta-analysis shows that studies like the Bennell et al. paper used by ODG used an ultra-low dose “PRP” preparation that is more likely to be associated with study failure. This is the same conclusion as my analysis of the 100+ PRP RCTs. In other words, all failed PRP RCTs must be examined to determine whether they used a PRP with a high enough dose for a positive treatment effect.

The Magic Trick

So, if recent 2024 guidelines confirm that PRP is effective, how did ODG conclude the opposite? It’s a classic magic trick using misdirection. Throw a bunch of old systematic reviews in the pot and stir to confuse the audience, who will be so busy looking at the impressive-appearing citations that they neglect to notice the problem. Then, throw in a single large study that never used PRP in the first place and that nobody will take the time to research. Finally, just write a review paragraph for all knee diagnoses that doesn’t focus on knee OA. “Voila,” the trick is complete!

The upshot? A single deep dive on knee OA and the ODG PRP guideline used by the state of California worker’s comp system shows that it’s one big magic trick. It cherry-picks papers and documents to support its non-coverage decision rather than performing a balanced review of the state of the PRP literature. Hence, if you practice in California or are a California patient, please copy and paste my review and submit it with your worker’s comp claims!

__________________________________________________________

References:

- Moraes VY, Lenza M, Tamaoki MJ, Faloppa F, Belloti JC. Platelet-rich therapies for musculoskeletal soft tissue injuries. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD010071. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010071.pub3. (PubMed: 24782334)

- Dragoo JL, Wasterlain AS, Braun HJ, Nead KT. Platelet-rich plasma as a treatment for patellar tendinopathy: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2014 Mar;42(3):610-8. doi: 10.1177/0363546513518416. Epub 2014 Jan 30. Erratum in: Am J Sports Med. 2016 Jul;44(7):NP38. PMID: 24481828.

- Dregalla RC, Lyons NF, Reischling PD, Centeno CJ. Amide-type local anesthetics and human mesenchymal stem cells: clinical implications for stem cell therapy. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014 Mar;3(3):365-74. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0058. Epub 2014 Jan 16. PMID: 24436443; PMCID: PMC3952925.

- Andia I, Maffulli N. Muscle and tendon injuries: the role of biological interventions to promote and assist healing and recovery. Arthroscopy 2015;31(5):999-1015. DOI: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.11.024. (PubMed: 25618490)

- Davey MS, Hurley ET, Withers D, Moran R, Moran CJ. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with platelet-rich plasma: a systematic review of randomized control trials. Arthroscopy 2020;36(4):1204-1210. DOI: 10.1016/j.arthro.2019.11.004. (PubMed: 31987693)

- Figueroa D, Figueroa F, Calvo R, Vaisman A, Ahumada X, Arellano S. Platelet-rich plasma use in anterior cruciate ligament surgery: systematic review of the literature. Arthroscopy 2015;31(5):981-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.11.022. (PubMed: 25595696)

- Liddle AD, Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of patellar tendinopathy: a systematic review. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2015;43(10):2583-90. DOI: 10.1177/0363546514560726. (PubMed: 25524323)

- Dai WL, Zhou AG, Zhang H, Zhang J. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy 2017;33(3):659-670.e1. DOI: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.09.024. (PubMed: 28012636)

- Bennell KL, et al. Effect of intra-articular platelet-rich plasma vs placebo injection on pain and medial tibial cartilage volume in patients with knee osteoarthritis: the RESTORE randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 2021;326(20):2021-2030. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2021.19415. (PubMed: 34812863)

- Chu J, Duan W, Yu Z, Tao T, Xu J, Ma Q, Zhao L, Guo JJ. Intra-articular injections of platelet-rich plasma decrease pain and improve functional outcomes than sham saline in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2022 Feb 6. doi: 10.1007/s00167-022-06887-7. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35124707.

- Kolasinski SL, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care & Research 2020;72(2):149-162. DOI: 10.1002/acr.24131. (Reaffirmed 2023 Apr) (PubMed: 31908149)

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Management of Osteoarthritis of the Knee (Non-Arthroplasty). Evidence-Based Guideline 3rd Ed [Internet] American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2021 Aug Accessed at: https://www.aaos.org/. [accessed 2023 Sep 28]

- Mautner K, Malanga GA, Smith J, Shiple B, Ibrahim V, Sampson S, Bowen JE. A call for a standard classification system for future biologic research: the rationale for new PRP nomenclature. PM R. 2015 Apr;7(4 Suppl):S53-S59. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.02.005. PMID: 25864661.

- Berrigan WA, Bailowitz Z, Park A, Reddy A, Liu R, Lansdown D. A Higher Platelet Dose May Yield Better Clinical Outcomes for PRP in the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy. 2024 Mar 19:S0749-8063(24)00206-8. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2024.03.018. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38513880.

- Patel S, Gahlaut S, Thami T, Chouhan DK, Jain A, Dhillon MS. Comparison of Conventional Dose Versus Superdose Platelet-Rich Plasma for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Prospective, Triple-Blind, Randomized Clinical Trial. Orthop J Sports Med. 2024 Feb 26;12(2):23259671241227863. doi: 10.1177/23259671241227863. PMID: 38410168; PMCID: PMC10896053.

- Bansal, H., Leon, J., Pont, J.L. et al. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in osteoarthritis (OA) knee: Correct dose critical for long term clinical efficacy. Sci Rep 11, 3971 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83025

- Berger DR, Centeno CJ, Steinmetz NJ. Platelet lysates from aged donors promote human tenocyte proliferation and migration in a concentration-dependent manner. Bone Joint Res. 2019 Feb 2;8(1):32-40. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.81.BJR-2018-0164.R1. PMID: 30800297; PMCID: PMC6359887.

- Laver L, Filardo G, Sanchez M, Magalon J, Tischer T, Abat F, Bastos R, Cugat R, Iosifidis M, Kocaoglu B, Kon E, Marinescu R, Ostojic M, Beaufils P, de Girolamo L; ESSKA‐ORBIT Group. The use of injectable orthobiologics for knee osteoarthritis: A European ESSKA-ORBIT consensus. Part 1-Blood-derived products (platelet-rich plasma). Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2024 Apr;32(4):783-797. doi: 10.1002/ksa.12077. Epub 2024 Mar 4. PMID: 38436492.

- Mende E, Love RJ, Young JL. A Comprehensive Summary of the Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews on Platelet-Rich Plasma Therapies for Knee Osteoarthritis. Mil Med. 2024 Feb 28:usae022. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usae022. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38421752.

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.