New Research: Your Achilles Tendon Is an Efficient and Twisted Mess

As a physician, like every other doctor, I was taught that the Achilles was the biggest single tendon in the human body. The first day of medical school I was also told that half of everything they would teach me would eventually be proven wrong. So this past week, researchers added yet another thing that all doctors believe is true and blew it away. Turns out the Achilles isn’t one tendon but three twisted tendons! This discovery has major implications for how we fix these torn tendons, so if you’re planning on Achilles surgery, you better make sure your doctor got the memo.

The Achilles Tendon Explained

Alila Medical Media/Shutterstock

The Achilles tendon lives at the back of the ankle where it stretches from the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles (the muscles that form the calf muscle) down to the back of the calcaneus (the heel bone). The Achilles tendon is strong and thick, a bit like an industrial-strength rubber band, and for good reason: it is put under a lot of pressure every day. With every step we take, the tendon is constantly stretching and compressing. Add physical activities to the mix (e.g., sports, dance, running, etc.), and the Achilles tendon can experience enormous stress.

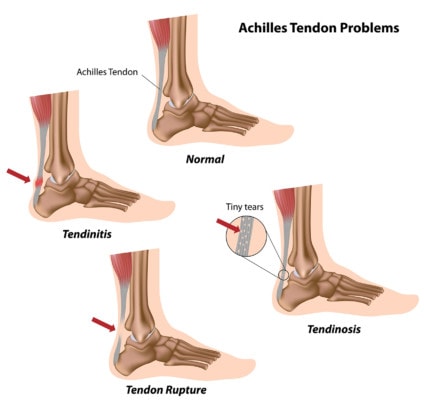

Despite its strength, when the Achilles tendon becomes overworked or has too much loading, injuries are common, which can include tendinopathy (aka tendinosis), partial tears, complete nonretracted tears (where the tendon is torn but still together) and full ruptures (a complete tear where the tendon snaps back like a rubber band). Additionally, Quinolone antibiotics (e.g., Cipro and Levaquin) have also been shown to cause Achilles tendon ruptures.

Invasive surgeries are often recommended for Achilles tears, which involve sewing the torn pieces of the tendon back together. Recoveries are lengthy, complication and failure rates are high, and one study found that Achilles tear surgery is no better than simply immobilizing and bracing the ankle for a few weeks.

The Achilles Tendon’s Role in the Interconnected Musculoskeletal System

Your body is very interconnected. This is despite the fact that you’ve likely been taught to view it as this piece or that piece. Let’s explore how that works with the foot, ankle, knee, and spine.

Biomechanical forces on the Achilles tendon, such as those that create instability following a bad ankle sprain, for example, have been shown to be one catalyst that can lead to knee arthritis. How can the ankle affect the knee? The deep muscles that live behind the knee connect to tendons that bridge all the way down to the Achilles tendon. So if there is pain in the back of the knee, the source could be instability in the Achilles tendon, and if left unaddressed, this could cause more damage, such as knee arthritis.

So why is the body’s strongest tendon so vulnerable to Achilles tendon injuries? The answer seems to lie in the fact that it’s not one tendon, but three twisted ropes.

Turns Out Your Achilles Is One Twisted Tendon!

The new study investigated specifically the forces of the three different calf muscles (soleus, lateral gastrocnemius, and medial gastrocnemius) on the Achilles tendon. What’s new about this research is that it identified that the Achilles tendon has three different and twisted subtendons. All three muscles have different functions, so this makes sense that all three connect via different tendon “ropes” to the heel bone, creating different degrees of stress on the tendon. The study suggests that it’s this “nonuniform loading” (pressure on a twisted tendon) that may make it so vulnerable to injury.

Translation? Think back to that thick industrial-strength rubber band. As a whole rubber band, it can stand up to heavy forces, but if we have smaller rubber bands that make up one whole structure and we twist them, one of those smaller and weaker bands can get loaded in a weird way and snap or become damaged.

What does all this look like? Check out the diagram below. The MG and LG parts represent the medial gastroc and lateral gastroc muscle tendons within the Achilles (inside and outside calf). The SOL part represents the soleus tendon, which is a deep postural muscle involved in standing that lives under the calf muscle. Look at the way these three subtendons twist as they go from top to bottom (proximal to distal) and you’ll get a real sense of why the Achilles is so vulnerable to injury.

Fixing the Achilles Without Surgery?

Now that we know that the Achilles is broken into subtendons, restoring normal function through surgery just got a lot harder! Now the surgeon needs to carefully align these three twisted subtendons, but since most surgeons don’t know that these exist, you’re more likely than not to end up with a misaligned tendon. Hence, if you have a partial tear or even a tear that you’ve been told is complete, it’s likely better to use a precise ultrasound-guided injection of your own platelets or stem cells to help the area heal and let the body do the heavy lifting and reconnecting of its own subtendons. However, if you do need a surgery, make sure your surgeon has gotten the memo that unless he carefully aligns these bands within the Achilles, you may well end up with an untwisted and less functional tendon.

The upshot? What’s fascinating here is that what many physicians consider is one structure, is actually not. Like the ACL and PCL ligaments in the knee, the body has developed the Achilles into parts that serve different functions. While this gives the tendon more flexibility in supporting walking, running, and jumping by more accurately transferring forces from three different muscles to the heel bone, it also creates areas of weakness as we age. In addition, it now creates much more work for any surgeon sewing a torn Achilles back together. Therefore, for most tendon tears, it’s likely better to make sure it’s aligned and then stimulate the body to heal with a precise injection of orthobiologics and let it figure out where everything goes!

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.