Do Orthopedic Stem Cell Treatments Really Have High Complication Rates?

Part of my job is looking at what’s being published in the world of orthopedic autologous cell therapies. Most of the time there is a steady flow of research supporting the safety and efficacy of various types of therapies and some research that doesn’t support this or that clinical application. However, every once in a while there is a paper that can’t support any of its conclusions that sneaks through peer review. This morning we’ll go over such a paper that claims that autologous stem cell therapies have a high complication rate.

My Job

My Dad had an expression that he was the “chief cook and bottle washer”. He meant that it was his job to wear lots of hats. That’s often where I find myself as founder and Chief Medical Officer for Regenexx. One of those varied jobs is to keep my eye out for new publications in this field. In fact, way back when, that was one of the reasons I began this blog as it forces me every morning at 5 am to see what’s new and write about that topic.

When new clinical trials come out, I collect them and every year I publish an annual infographic on new publications on the use of orthopedic stem cells. Every once in a while, however, a study gets published that can’t begin to support its conclusions and makes no sense when compared to the rest of the body of literature. I then either blog that study or submit a scientific rebuttal or both.

That study this morning is an article that takes a little bit of information and attempts to extrapolate it way beyond its actual meaning. This one is so bad that it’s hard to believe that any peer reviewer who was assigned this paper actually read the paper. What’s even more astounding is that major news organizations have seized on this paper as “proof” that orthopedic cell therapies have high complication rates. Let’s dig in.

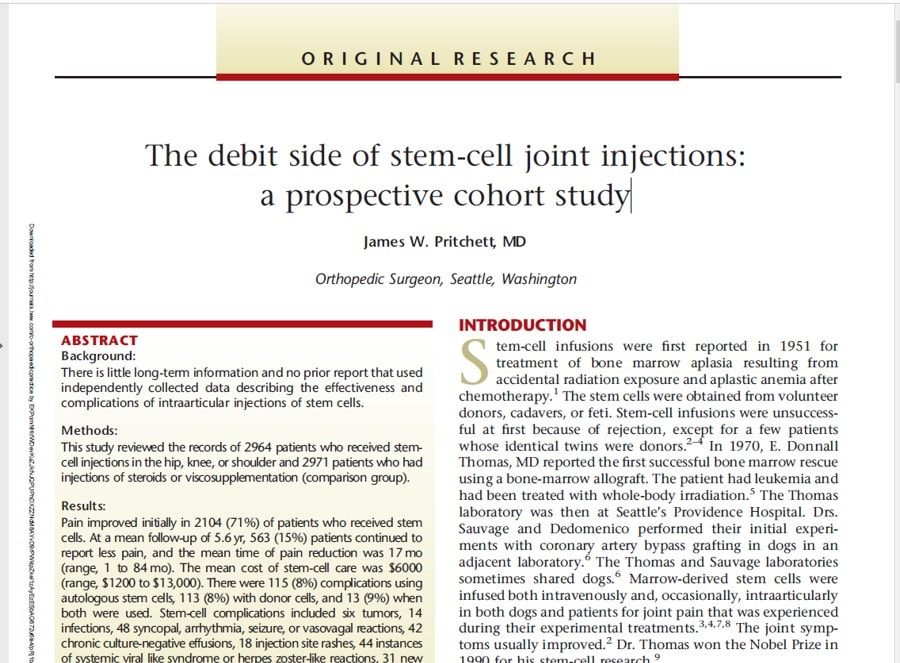

The debit side of stem-cell joint injections: a prospective cohort study

This paper recently was cited in a news article and was published in the journal Current Orthopedic Practice. Is this a big and important journal? Nope, it has a very low impact factor, meaning that experts in the field rarely cite articles in this journal as authoritative. Be that as it may, what’s more important is whether this article can support its conclusions. What were the shocking conclusions? That autologous orthopedic stem cell therapy has a complication rate of 8% and that includes tumors. Say what?

In summary, a single orthopedic surgeon author (James Pritchett of Seattle) had someone else pull a bunch of insurance data from orthopedic stem cell therapy reimbursement claims submitted through health savings accounts. This was on both autologous therapies (from the patient) and allogeneic (from a donor). There was then a review of that data, which was poorly described in the paper, and then conclusions were drawn about complication rates.

Digging into Why this Paper Is a Mess

It’s hard to know where to begin with this jumbled mess of words and concepts calling itself high-level research. While there is more wrong than I review here, I had to hit the high points or risk boring everyone to death. Let’s dig in by category of malfeasance:

Miscatorgizing It’s Importance

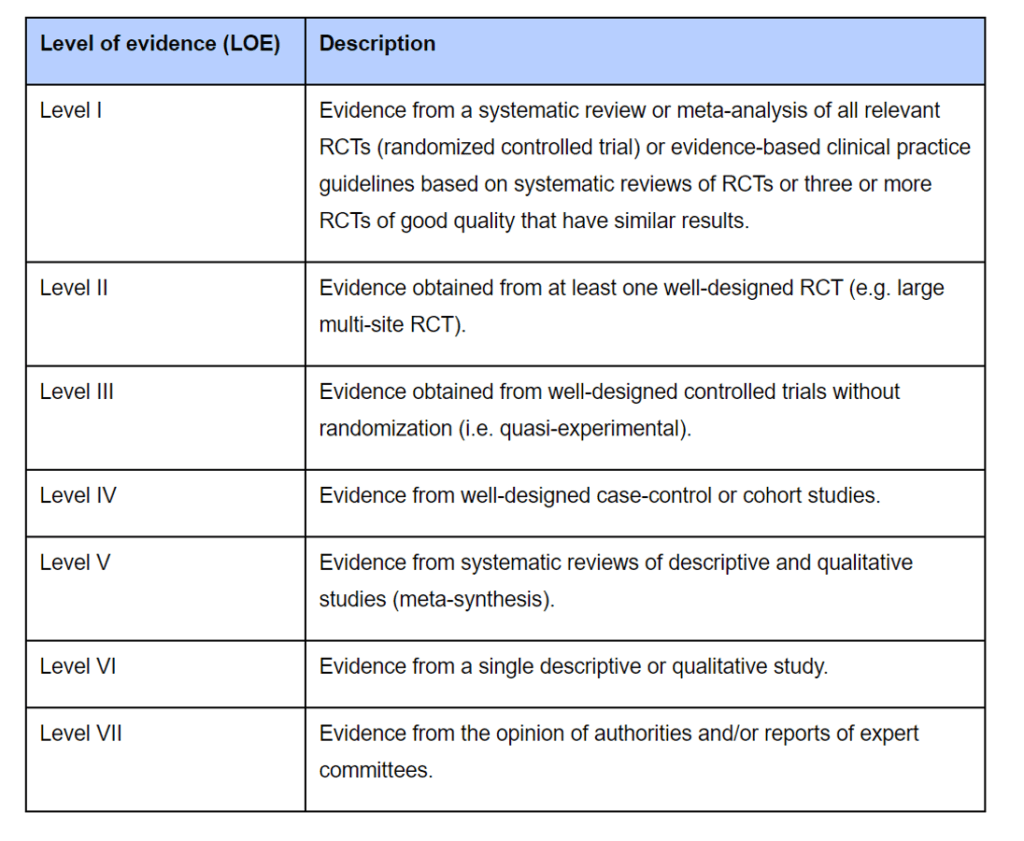

The study was categorized in the abstract as “Level II” evidence. What does that mean? Here’s the standard interpretation of those evidence levels:

What is level II evidence? That’s a randomized controlled trial where the patients are randomly assigned into different treatment groups. What is this paper? An incomplete retrospective analysis of insurance claims. What is the correct category of evidence? This is an after-the-fact paper, so it’s probably level V or lower. Bizarrely, the author also claims in the title that the study is prospective, which would mean that he designed and participated in the collection of data on patients as they were treated. However, these treatments had already happened and the author wasn’t involved in how the data was reported. Hence, that characterization is also not accurate.

An Unsure Denominator

In order to determine the rate of complications, we need a clean case series. That means that we know how many patients were treated, usually because we treated them. That becomes the denominator as we figure out a rate. For example, if we know that 100 patients were treated and 10 had a complication, then the complication rate is 10%. The problems begin when we have no idea how many patients were actually treated. In this paper, that’s exactly what’s happening, as the author has no idea of the total number of patients treated that generated the complications reported in this insurance data.

This is what the paper says about how it got its data:

“The database was provided by a consulting group within an insurer. This consulting firm provided advice and administrative service in support of employee benefit programs administering Health Savings Accounts (HSA) and Flexible Savings Accounts (FSA). Payment for stem-cell injections is not a covered service under most health insurance plans because the treatment is considered experimental or investigational by most insurers. However, with medical necessity documentation and proof of medical treatment, payment is possible for stem-cell injection under many HSA and FSA programs. The consulting firm also provided consulting for the health benefit programs associated with the HSA and FSA accounts and had access to the medical records documenting the complications that occurred.”

So the author had no control over what was in the dataset? Huh? He doesn’t even show the methods used by the consulting group to find these claims. Why is that a very serious issue?

- There is no code for orthopedic stem cell therapy. That means that the insurer or consultant couldn’t run a report on a specific CPT payment code to find all of these claims. That means that the only way these claims could have been found is to run free-text searches of the insurance system. Since this would have relied on many people processing claims typing in what the claim was for, it’s more likely than not that many claims for orthopedic stem cell therapy were missed.

- Larger claim records would have been easier to find. Given that the insurer is trying to find a needle in a proverbial haystack of millions of claims, those records that were larger with more entries would have been easier to find. Those would be more likely to be the claims with complications that the insurer also reimbursed.

Again, the fact that there is zero description of the search methodology here is such a debacle that it can’t be ignored. The basic tenets of science require that someone else can read your work and replicate it. This can’t happen here as we have not a clue how this data was collected.

Sloppy Causation

About a decade ago I helped author a paper on the causation of injuries (2). That paper has been cited by the federal courts as the method judges should use to determine if A was caused by B. Hence, it has turned out to be authoritative in the field.

There are three key elements to looking at causation. For this discussion, I’ll focus on if a complication was caused by a stem cell procedure:

- Biologic plausibility – Is there a biological mechanism that explains how the stem cell procedure caused that specific complication?

- Temporal association – Did the complication happen shortly after the procedure? If not, was it expected to occur later based on that type of complication? Usually, a window of thirty days is used in orthopedic studies, but this window could be extended if we’re talking about something like a tumor.

- Lack of alternative explanations – Are there better explanations for the complication?

So how did our orthopedic surgeon do in his causation analysis of possible complications? Poorly. He only used the concept that the complication happened after the procedure, but provided no additional analysis. Meaning he skipped the other two critical elements of determining if the complication was actually related to the procedure. Basically, his causation analysis would never pass muster in a federal courtroom, so it certainly shouldn’t have passed muster in a medical journal.

Sloppy Treatment Identification

In order to know which treatment the author found to have a high complication rate, we would need to know which treatment was used. For example, in the world of autologous “stem cells” that are injected into joints, this is a shortlist of very different therapies:

- PRP-Platelet Rich Plasma – this is not a stem cell-based treatment, but many authors misidentify it as one.

- Bone Marrow Aspirate – this is the unconcentrated liquid portion of the bone marrow

- Bone Marrow Concentrate (BMC) – this is the concentrated liquid portion of the bone marrow

- Adipose Fat Graft – unprocessed fat taken from a liposuction

- Adipose Micro Fragmented Fat Graft – minimally processed fat that is finely chopped

- Adipose Stromal Vascular Fraction – fat that is digested with an enzyme and then centrifuged to concentrate nucleated cells

- Culture Expanded Mesenchymal Stem Cells – Bone marrow or fat mesenchymal stem cells which are isolated and grown in culture to greater numbers.

- The Apheresis Collected Nucleated Cell Fraction of Whole Blood – Blood which is run through a machine to collect and concentrate the nucleated cells. This can be done with or without giving the patient a drug to mobilize stem cells from the bone marrow

So which of these technologies were used in this paper and what were the specific complication rates for each? We have no idea. The study made no attempt to report this data. This brings up how poor the data collection was based on the medical records submitted to an insurance company. Meaning, if the records were good, we would know here which procedure was used. This is why a study like this would always be considered very low-quality data.

Tumors?

The study claims to have found 3 tumors that were felt to be related to autologous stem cell joint injections out of 1,423 patients. First, we know that this was a very old group given that 2% of the patients in the group died over 4 years of natural causes! However, amazingly, there is no report of the mean age of the patients in the article. So somehow the author was able to report from a review of submitted medical records that about 1% identified non-binary but neglected to report the ages that were treated? This is getting pretty bizarre…

What is defined as a tumor? Is a cyst considered a tumor? We don’t know. We do know that 3 of the 6 total reported tumors were characterized (it’s not disclosed if these were from allogeneic or autologous injections) and found to be benign. In fact, a colleague called Dr. Pritchett who admitted that these weren’t actually neoplasms (cancerous tumors), but merely areas of tissue reaction.

Has anybody published a higher-quality study looking at tumor formation in autologous cell therapies? Yes, Phillipe Hernigou has done this study with almost 2,000 patients and reported his results with better data collection methods including x-rays of the sites in patients with known neoplasm at the time of BMC treatment and overall neoplasm rates in a larger BMC treated population (3,4). He found nothing like this. Neither did our study of even more patients that were actually tracked in a registry. These were then adjudicated with a panel that included university physicians (5).

Did the three tumors that occurred in autologous joint injections use bone marrow concentrate? Again, we don’t have that data from this poorly written study. However, higher-level data already exists that refutes this contention that joint tumors are somehow rare side effects of these procedures.

Patient Exclusions

So how many patients were excluded? That’s critical because you really can’t exclude any or many patients if you’re going to report an accurate complication rate. Turns out, quite a few. The study began with records on 6,117 patients who had intra-articular injections and ended up excluding most of them down to 2,964 patients. Meaning the study author got rid of more than half of the patients. The largest excluded group had other procedures within the 4-year study review period. However, that doesn’t make much sense as if a complication did occur, it would be most likely to occur in the first 30 days.

Relying on the Medical Records a Causation Analysis

One of the weakest parts of this study is the fact that it relied on medical records that were submitted to insurance companies. For example, I’m the medical expert on the vast majority of Liveyon infection cases (some of which were likely included in this study). I have reviewed thousands of pages of those medical records. While you can glean some information from the records submitted by the treating doctor, trying to determine if a possible complication occurred due to a stem cell injection is very difficult even if there is a lawsuit where all of the providers are legally compelled to submit records. Getting all of that together takes these law offices months and many requests from various medical offices involved in treating the complication. So do I believe for a second that this physician had easy access to all of the medical records for the medical care to accurately determine causation? NO. There is no requirement to submit medical records for covered items. Hence, the insurer wouldn’t generally have the medical records that detailed the complication. What would they have? Billing codes, but trying to figure out if those codes were related to the event is almost impossible.

The Comparison Group wasn’t Matched to the Stem Cell Group

The author attempted to include a “comparison” group which was again a bunch of insurance claims. These were injections for steroid and hyaluronic acid (HA) injections (viscosupplementation). However, there was NO attempt to age or severity match these patients. This is a serious issue. For example, HA injections tend to be used more often in patients with mild arthritis whereas the age of the “stem cell” treated population here tells us that this was likely a severe osteoarthritis group (older and more prone to complications). In addition, many people seek out orthobiologic procedures after they have failed covered injection care including steroid and HA shots, which then artificially selects the “stem cell” group for having more severe osteoarthritis. Yet another issue is that the medical records on the steroid/HA group would be even more cursory than the “stem cell” group as no medical notes are required to reimburse for steroid injections or viscosupplementation.

In addition, there was likely selection bias likely introduced by the physicians treating the complications. For example, given that orthopedic “stem cell” treatment is still novel, there was likely a higher rate of connection between these claims and subsequent complications. The opposite would be true with a steroid or HA injection. These are commonplace, so connecting an infection or effusion in a patient with degenerative joint disease to these events would be less likely. This creates a perfect storm of artificially increased complications in the “stem cell” group and artificially reduced complications in the injections as usual group. This is why no scientist would trust this type of data review to compare complication rates.

What is the Actual Complication Rate in Studies Where Patients Were Actually Prospectively Followed?

This “study” reported complication rates of 8% (AE’s or Adverse Events) for autologous cell therapies. Less than 1% of these were SAE’s (Serious Adverse Events that require treatment). Meaning the vast majority of what was reported resolved on its own. While some of these could be clearly associated with a joint injection (i.e. infection), others were likely indications of disease progression. Meaning this was an elderly group treated for likely end-stage osteoarthritis. So disease progression would look like continued worsening pain and swelling. The only way to tell the difference would require much more in the way of medical record review and direct patient and provider interviews.

So what is the SAE complications rate in studies with far better methodologies? Our study treated and tracked 2,372 patients over 9 years in a registry designed to detect complications and then adjudicated those complications via an independent panel. Meaning I didn’t adjudicate the SAEs, that job was done by a panel of private practice and academic experts not associated with our company. Of the 0.9% of patients treated with bone marrow concentrate who had a reported SAE (a complication that required any kind of treatment), almost all of those were not directly related to the procedure.

How about other authors? In fact, more than 200 papers have been published on orthopedic stem cell use of all types through private practice physicians and academics representing ten thousand plus procedures and nobody has reported serious complication rates (like tumors) anywhere near these levels. All of these studies would be high-level and better quality data than that reported in this study.

In Summary

This is a paper that claims to be a randomized controlled trial but that treated no patients and had no valid controls. The data was gleaned likely from free text searches of data center notes to find “cases” which is a method that likely biased towards complications because those would have had more insurance entries. There was no attempt made to adjudicate complications and the data available was limited to whatever the provider submitted to document the insurance claim. Hence, any analysis of why another care event occurred (i.e. possible treatment for a complication) and whether it was related to the intra-articular stem cell procedure was sketchy at best. In addition, there was no attempt to determine which individual treatment types were used, likely because accurately deciphering that from the submitted notes was problematic. In addition, the “tumors” that were identified that were worked up weren’t classified as either autologous or allogeneic and in a direct quote from the author weren’t actually neoplasms. Also, no attempt was made to match the comparison group to the “stem cell” group. Finally, higher-level data than this paper already exists on common intra-articular “stem cell” treatments like bone marrow concentrate and micro-fragmented fat and none of that work was cited by this author. In particular, that published data doesn’t match up with what was reported in this paper.

The upshot? It’s hard to believe that this paper was allowed to be published “as is”. Everything from the title to the evidence classification to the way the data was collected is so deeply flawed that all that can be concluded is that some orthopedic surgeon looked at insurance information and this is what he found. The paper is also so poorly written that there is no way to replicate the methodology as we have no idea of the basic methods of data collection. Hence, this paper never should have made it through basic peer review.

_____________________________________

References

(1) Pritchett, J. The debit side of stem-cell joint injections: a prospective cohort study. Current Orthopaedic Practice. Publish Ahead of Print. 10.1097/BCO.0000000000000961. 2021

(2) Freeman MD, Centeno CJ, Kohles SS. A systematic approach to clinical determinations of causation in symptomatic spinal disk injury following motor vehicle crash trauma. PM R. 2009 Oct;1(10):951-6. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.07.009. PMID: 19854423.

(3) Hernigou P, Flouzat Lachaniette CH, Delambre J, Chevallier N, Rouard H. Regenerative therapy with mesenchymal stem cells at the site of malignant primary bone tumour resection: what are the risks of early or late local recurrence? Int Orthop. 2014 Sep;38(9):1825-35. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2384-0. Epub 2014 Jun 7. PMID: 24906983.

(4) Hernigou P, Homma Y, Flouzat-Lachaniette CH, Poignard A, Chevallier N, Rouard H. Cancer risk is not increased in patients treated for orthopaedic diseases with autologous bone marrow cell concentrate. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013 Dec 18;95(24):2215-21. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00261. PMID: 24352775.

(5) Centeno CJ, Al-Sayegh H, Freeman MD, Smith J, Murrell WD, Bubnov R. A multi-center analysis of adverse events among two thousand, three hundred and seventy two adult patients undergoing adult autologous stem cell therapy for orthopaedic conditions. Int Orthop. 2016 Aug;40(8):1755-1765. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3162-y. Epub 2016 Mar 30. Erratum in: Int Orthop. 2018 Jan;42(1):223. PMID: 27026621.

If you have questions or comments about this blog post, please email us at [email protected]

NOTE: This blog post provides general information to help the reader better understand regenerative medicine, musculoskeletal health, and related subjects. All content provided in this blog, website, or any linked materials, including text, graphics, images, patient profiles, outcomes, and information, are not intended and should not be considered or used as a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please always consult with a professional and certified healthcare provider to discuss if a treatment is right for you.