ACL Tear Management Without Surgery In Phoenix, AZ – Mountain View

Do you have an MRI-confirmed partial or complete tear of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and have been told that surgery is your only option?

Procedures using Regenexx lab processes, including Perc-ACLR (percutaneous ACL repair), may offer a non-surgical alternative for treating certain ACL injuries. Developed as a less invasive option, this approach utilizes interventional orthobiologics to support the body’s natural healing process.

ACL injuries are among the more frequently addressed knee conditions by physicians in the licensed Regenexx network. In appropriate cases—particularly those involving non-retracted partial or full tears, these procedures may help reduce pain and improve joint stability, without the need for traditional surgical intervention.

Repair of ACL tear without surgery

ACL Tear Recovery Time Without Surgery

When considering how to move forward after an ACL injury, it’s important to weigh all your options, including your recovery timeline, your ability to return to activity, and the potential long-term impact on joint health. Procedures using Regenexx lab processes are designed to preserve the ACL whenever possible, rather than remove or replace it.

Perc-ACLR (percutaneous ACL repair) is a procedure that utilizes image-guided injections of your own bone marrow concentrate. This process is completed in a single day and is considered less invasive than traditional surgical approaches. In appropriate cases, this option may offer a shorter recovery period and help support the body’s natural healing response.

| Perc-ACLR | Surgery | |

|---|---|---|

| Procedure Invasiveness | Much less | Much more |

| Return to Sports | 3 to 6 months | 1 year |

| Keep your ACL | Yes | NO |

| Recovery | Brace, much less extensive PT | Crutches, brace, extensive PT |

2222 East Highland Avenue

Phoenix, AZ 85016

Request an Appointment

Call to Schedule Schedule OnlineClinic Hours

| Sunday | Closed |

| Monday | 8AM–4PM |

| Tuesday | 8AM–4PM |

| Wednesday | 8AM–4PM |

| Thursday | 8AM–4PM |

| Friday | 8AM–4PM |

| Saturday | Closed |

How Does the Regenexx Approach Work?

The Regenexx approach utilizes interventional orthobiologics, a specialized method of orthopedic care developed as a less invasive alternative to ACL surgery. These procedures use imaging guidance, such as ultrasound, to deliver your own bone marrow concentrate precisely to the site of injury within the joint.

The cellular components in bone marrow concentrate may help support the body’s natural healing response. In appropriate cases, this approach may assist in addressing ACL tears without the need for surgery1.

Regenexx for ACL Tears: Perc-ACLR

Available at Mountain View Headache and Spine Institute – Phoenix, AZ

Perc-ACLR is a procedure using Regenexx lab processes that may offer a less invasive alternative to traditional ACL surgery. At Mountain View Headache and Spine Institute in Phoenix, AZ, this process typically occurs over one day.

The procedure begins with the physician extracting a small amount of bone marrow using precise imaging guidance and a specialized technique licensed by Regenexx. After the bone marrow is drawn, it is processed by a trained lab technician following Regenexx protocols. Patients typically have a period of rest before reinjection, which occurs approximately three to six hours later.

Fluoroscopy (real-time X-ray guidance) and MRI imaging with contrast are used to create a detailed map of the ACL tear. This imaging roadmap helps guide the physician in placing the processed bone marrow concentrate into the affected areas of the ligament. Local anesthesia is applied to enhance comfort during the reinjection.

Following the procedure, mild joint soreness may occur for one to three days, with discomfort generally decreasing within five to seven days. Many individuals report functional improvement within a month and may begin physical therapy and light activity during early recovery.

Am I a candidate?Note: As with all medical procedures, outcomes can vary. Procedures using Regenexx lab processes have both success and failure rates. Patient experiences shared in reviews or testimonials should not be interpreted as an assurance of outcome for others.

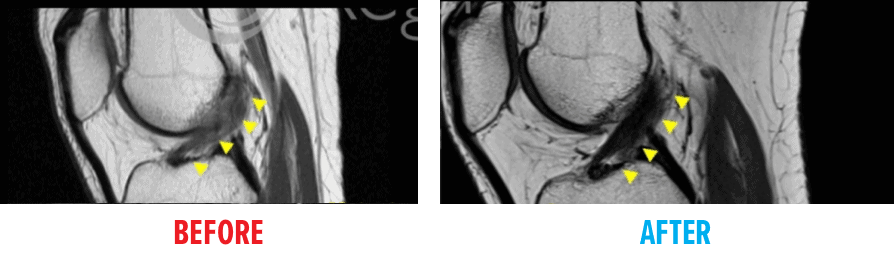

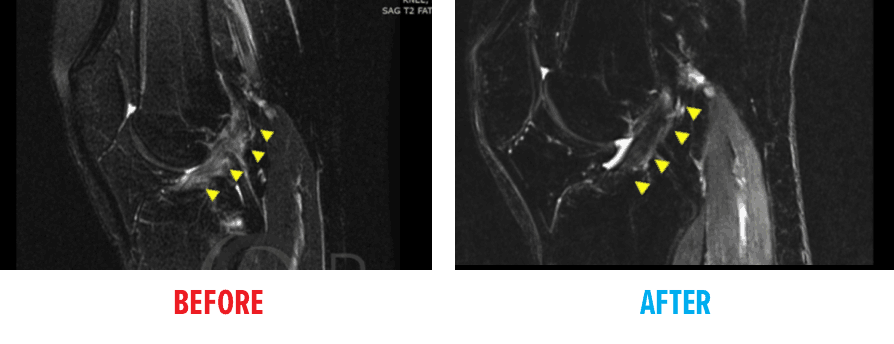

Before and After MRI Images

These MRI images illustrate the changes observed in individuals who underwent procedures using Regenexx lab processes as an alternative to ACL surgery.

In the before image, the ACL appears disrupted. In contrast, the after image shows a more continuous dark band running diagonally, an appearance typically associated with a more intact ligament structure.

FAQs

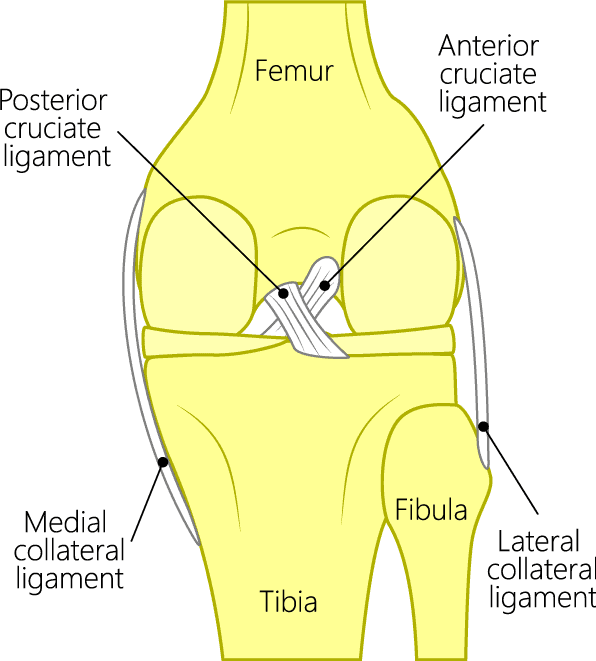

Knee joint anatomy showing ACL

The knee joint contains two cruciate ligaments—named for their cross-like arrangement—that help stabilize the joint. These ligaments intersect to form an X: the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is positioned at the front, while the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) lies at the back. The ACL prevents the shinbone from sliding too far forward, and the PCL stops it from sliding backward.

ACL surgery is typically not considered an emergency unless there is severe damage to surrounding structures, pronounced joint instability, or unmanageable pain. In many cases, adults with some degree of knee stability can postpone surgery for one to two months. For young athletes, the recommended waiting period may be shorter, often influenced by the goal of a quicker return to sports. Some patients may benefit from starting with physical therapy to support recovery. If symptoms persist, nonsurgical alternatives like Perc-ACLR may be explored before proceeding with surgery.

Studies have shown that ACL sprains, and in some cases, even complete tears, may have the potential to heal without surgical intervention, particularly when interventional orthopedic treatments like the Perc-ACLR procedure are used. These non-surgical approaches harness the body’s natural healing mechanisms to support ligament repair. Given this potential for natural healing, surgical reconstruction may not be the only option for addressing ACL injuries.

ACL sprains, tears, and ruptures are often used interchangeably, as they all refer to varying degrees of injury to the anterior cruciate ligament. Clinically, these injuries are categorized as sprains and graded based on severity:

- Grade 1 Sprain: The ligament is slightly overstretched but remains intact and capable of maintaining knee joint stability.

- Grade 2 Sprain: The ligament is partially torn or more significantly stretched, resulting in some looseness within the joint. This is commonly referred to as a partial tear.

- Grade 3 Sprain: This represents a complete tear of the ligament, in which the ACL is fully disrupted, often split into two parts, leading to marked joint instability.

The term ACL rupture typically refers to a complete, full-thickness tear, equivalent to a Grade 3 sprain, and may involve visible ligament deformity or retraction.

Statistically, only about half of athletes who undergo ACL reconstruction regain full function after rehabilitation and are able to return to their previous level of sport. The remaining half may recover knee stability but often do not regain normal biomechanics or proprioception equal to the uninjured knee. Some may also experience functional limitations in daily life. It is advisable to seek a second opinion before proceeding with surgery, as conventional ACL reconstruction carries several documented risks and the initial injury may have been misdiagnosed. While surgery can be appropriate for certain cases, the majority of individuals may be able to avoid it.

Approximately 17 percent of adults report anterior knee pain or pain while kneeling after surgery, and between 5 percent and 29 percent experience graft failure and loss of knee stability, with higher failure rates seen in younger patients. Other potential complications include knee stiffness or loss of range of motion (approximately 5 percent), painful hardware (approximately 6 percent), infection (approximately 1 percent to 2 percent), and patellar tendon rupture or patellar fracture in cases involving bone-to-bone grafts.³⁻⁶

Rising participation in high-intensity elite sports among youth has led to increased ACL reconstruction surgeries in young teens. However, emerging research suggests that postsurgical complications may be more pronounced in children than in adults. If the goal is to preserve one’s natural physical structure and “keep original parts and structures intact,” a nonsurgical option like Perc-ACLR may be worth considering.

A large review of 160 clinical trials found higher complication rates among young adolescents undergoing ACL repair, including increased risk of growth disturbances, skeletal deformities, and ligament rerupture that may require revision surgery. The study focused on a skeletally immature population with an average age of 13.7

Additionally, a 2010 Swedish study challenged the belief that surgery is the only path to healing. Among athletes with an average age of 26 who followed a strict physical therapy regimen instead of surgery, 60 percent never required ligament reconstruction and were still able to return to sports.8

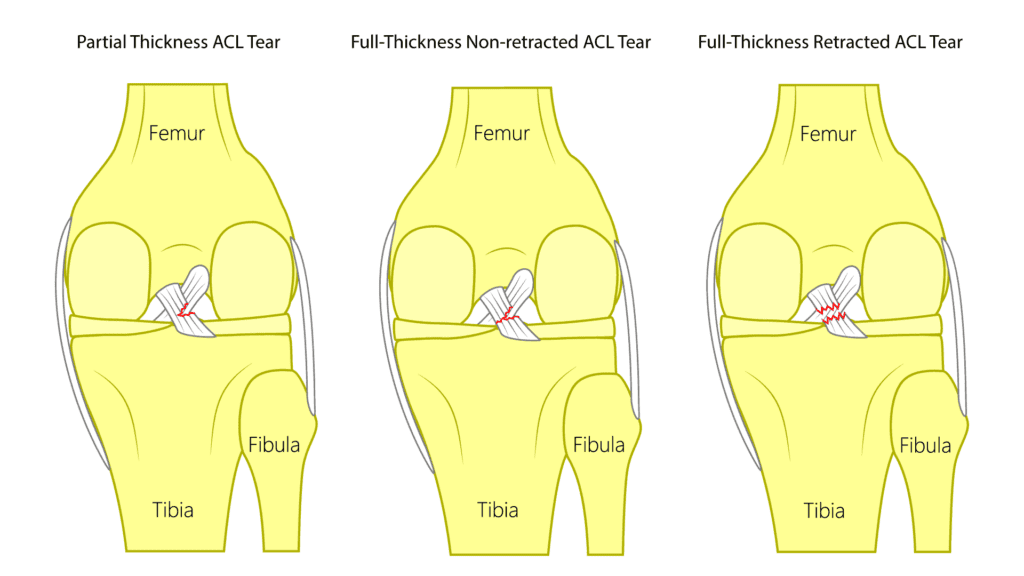

ACL tears can be classified in many ways, but within regenerative medicine, they are typically grouped into three primary types: partial-thickness, full-thickness non-retracted, and full-thickness retracted tears. Both partial-thickness and full-thickness non-retracted tears may be suitable for treatment using regenerative approaches such as the Regenexx knee Perc-ACL procedure, which promotes healing without the need for surgery. In contrast, full-thickness retracted tears usually require surgical repair to restore proper function.

- Partial-Thickness ACL Tear

A partial-thickness tear does not extend through the entire ligament. Imaging typically reveals that a portion of the ACL remains intact, indicating that the tear is incomplete. - Full-Thickness Non-Retracted ACL Tear

This type of tear involves a complete disruption of the ligament fibers; however, the torn ends have not separated significantly. The ligament is fully torn, but the pieces remain aligned and have not recoiled or retracted, making it potentially responsive to regenerative treatment. - Full-Thickness Retracted ACL Tear

In this case, the ligament has torn completely, and the ends have pulled apart—often recoiling like a stretched rubber band that snaps. This displacement generally limits the success of nonsurgical options and typically necessitates surgical reconstruction.

ACL tears

Request an Appointment

References

1. Centeno C, Markle J, Dodson E, Stemper I, Williams C, Hyzy M, Ichim T, Freeman M. Symptomatic anterior cruciate ligament tears treated with percutaneous injection of autologous bone marrow concentrate and platelet products: a non-controlled registry study. J Transl Med. 2018 Sep 3;16(1):246. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1623-3. PMID: 30176875. PMID: 30176875. [Google Scholar]

2. Costa-Paz M, Ayerza MA, Tanoira I, Astoul J, Muscolo DL. Spontaneous healing in complete ACL ruptures: a clinical and MRI study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012 Apr;470(4):979-85. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1933-8. PMID: 21643922. [Google Scholar]

3. Freedman KB, D’Amato MJ, Nedeff DD, Kaz A, Bach BR Jr. Arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a metaanalysis comparing patellar tendon and hamstring tendon autografts. Am J Sports Med. 2003 Jan-Feb;31(1):2-11. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310011501. PMID: 12531750. [Google Scholar]

4. Webster KE, Feller JA, Leigh WB, Richmond AK. Younger patients are at increased risk for graft rupture and contralateral injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2014 Mar;42(3):641-7. doi: 10.1177/0363546513517540. Epub 2014 Jan 22. PMID: 24451111. [Google Scholar]

5. Burks RT, Friederichs MG, Fink B, Luker MG, West HS, Greis PE. Treatment of postoperative anterior cruciate ligament infections with graft removal and early reimplantation. Am J Sports Med. 2003 May-Jun;31(3):414-8. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310031501. PMID: 12750136. [Google Scholar]

6. Kovacic JJ in Complications of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Surgery, AAOS Monograph Series 2005. Accessed August 25, 2020.

7. Wong SE, Feeley BT, Pandya NK. Complications After Pediatric ACL Reconstruction: A Meta-analysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2019 Sep;39(8):e566-e571. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001075. PMID: 31393290. [Google Scholar]

8. Frobell RB, Roos EM, Roos HP, Ranstam J, Lohmander LS. A randomized trial of treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tears. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 22;363(4):331-42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907797. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2010 Aug 26;363(9):893. PMID: 20660401. [Google Scholar]