ACL Tear Management Without Surgery In Ospina Medical – New York, NY

Have you been diagnosed through MRI with a partial or complete tear of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and told that surgery is your only option?

At Ospina Medical in New York, NY, physicians in the licensed Regenexx network offer Perc-ACLR (percutaneous ACL repair), a procedure developed by Regenexx to treat partial and full ACL tears without surgery. ACL injuries are among the most frequently treated knee conditions, and many non-retracted partial and complete tears may be addressed through this approach, except in the most severe cases.

ACL Tear Recovery Time Without Surgery

ACL Tear Recovery Time Without Surgery

There are several important factors to consider when choosing the right path for recovery, whether your goal is to return to sports, resume daily activities, or support your long-term joint health. Ospina Medical in New York, NY, focuses on preserving the ACL rather than replacing it. Existing research and extensive clinical experience support the potential for ACL injuries to heal naturally under the right conditions.

Perc-ACLR is a precisely guided injection procedure that uses your own orthopedic bone marrow concentrate. Performed under X-ray guidance, the procedure is completed in a single day. It is significantly less invasive than surgery and is generally associated with shorter recovery times.

| Perc-ACLR | Surgery | |

|---|---|---|

| Procedure Invasiveness | Much less | Much more |

| Return to Sports | 3 to 6 months | 1 year |

| Keep your ACL | Yes | NO |

| Recovery | Brace, much less extensive PT | Crutches, brace, extensive PT |

635 Madison Ave

Suite 1301

New York, NY 10022

Request an Appointment

Call to Schedule Schedule OnlineClinic Hours

| Sunday | Closed |

| Monday | 9AM–5PM |

| Tuesday | 9AM–5PM |

| Wednesday | 9AM–5PM |

| Thursday | 9AM–5PM |

| Friday | 9AM–5PM |

| Saturday | Closed |

How Does The Regenexx Approach Work?

Regenexx developed an approach to orthopedic care known as Interventional Orthopedics, a less invasive alternative to ACL surgery. This method uses image-guided injection technology, such as ultrasound, to deliver a precise injection of bone marrow concentrate directly to the area of injury within the joint.

The bone marrow concentrate contains components that may support the body’s natural healing response. When placed at the site of the ACL tear, these cells work in coordination with the body’s own repair mechanisms, offering a potential alternative to surgical intervention.1.

Regenexx For ACL Tears: Perc-ACLR

The procedure is typically completed in one day. A small amount of bone marrow is first collected using imaging guidance and a specialized extraction technique that is unique to Regenexx.

After the marrow is processed by a Regenexx lab technician, there is a rest period before the prepared bone marrow concentrate is reinjected into the ACL, generally three to six hours later.

Local anesthesia is applied, and the reinjection is performed under fluoroscopic guidance (real-time X-ray). MRI imaging combined with contrast dye is used to map the tear, providing a detailed visual guide for placing the bone marrow concentrate into the affected areas of the ligament.

Following the procedure, soreness around the joint is common for one to three days. Most individuals report a reduction in discomfort within five to seven days. Early signs of improvement in ACL function are often noted within the first month, with many beginning light activities and physical therapy during that time.

Am I a candidate?Note: As with any medical procedure, procedures using Regenexx lab processes may have varying outcomes. Reviews and testimonials presented on this site are individual experiences and should not be considered indicative of expected results for others.

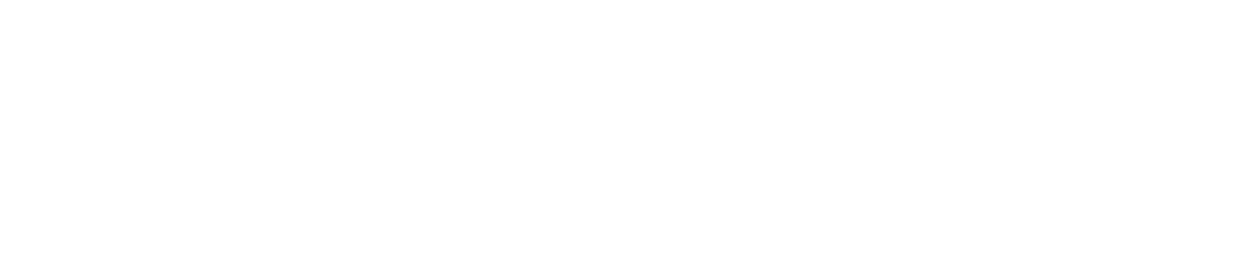

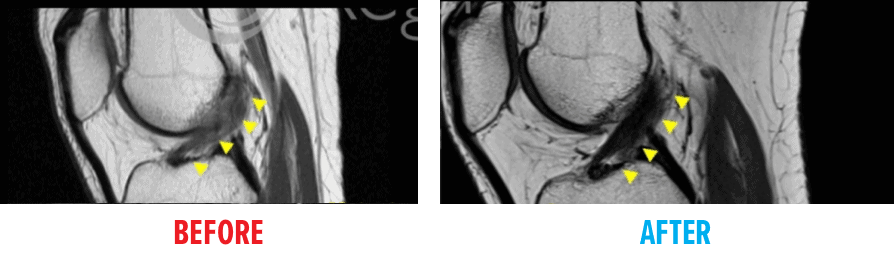

BEFORE and AFTER MRI Images

View the outcomes of individuals who received a procedure using the Regenexx protocol as an alternative to ACL surgery.

In the BEFORE image, the ACL appears torn. The AFTER image shows the area where the ACL should be a clear, dark diagonal band, indicating structural improvement following the procedure.

FAQs

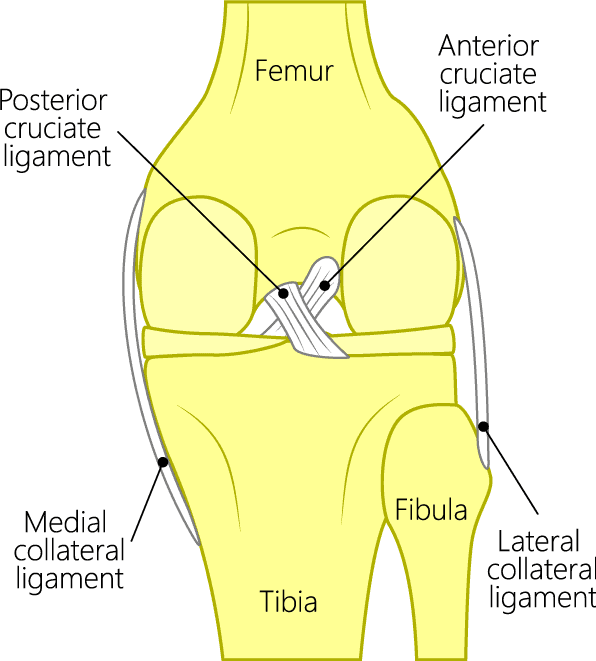

Knee joint anatomy showing ACL

Two cruciate ligaments, named for their cross-like shape, are located inside the knee joint and help provide stability. These ligaments intersect to form an “X”—with the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) positioned at the front and the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) at the back.

The ACL helps prevent the tibia (shin bone) from moving too far forward, while the PCL helps prevent it from shifting backward.

ACL surgery is not typically performed on an emergency basis unless there is severe damage to surrounding structures, marked instability, or significant pain. In cases where some joint stability remains, adults may be able to delay surgical intervention for several weeks.

For younger athletes, the timeframe may be shorter, often influenced by the goal of returning to sports as soon as possible. In some situations, starting with physical therapy may support recovery. If improvement is not achieved through conservative care, less invasive options, such as Perc-ACLR, may be considered before moving forward with surgery.

Some studies have indicated that ACL sprains and even certain complete tears may have the potential to heal without surgical intervention, especially when supported by interventional orthopedic procedures like Perc-ACLR. These approaches use the body’s own repair mechanisms and do not involve surgery.

When the body shows the ability to support natural healing of the ACL, it raises an important question: Is surgery always necessary?

ACL sprains, tears, and ruptures are terms that are often used interchangeably, as they all refer to injury of the ligament. Medically, knee ligament injuries are categorized as “sprains” and classified by severity.

- Grade 1 Sprains: The ligament is slightly stretched and may have minor damage, but continues to provide stability to the knee joint.

- Grade 2 Sprains: This indicates a moderate injury in which the ligament is partially torn or more significantly stretched, leading to some looseness in the joint.

- Grade 3 Sprains: Commonly referred to as a complete tear, this type of injury involves the ligament being fully torn into two sections, resulting in knee instability.

The term ACL rupture is typically used to describe a complete tear, often involving full-thickness damage, potential deformity, or retraction of the ligament, characteristics associated with Grade 3 injuries.

Statistics show that only about half of athletes who undergo ACL reconstruction regain full function after rehabilitation and return to their previous level of athletic activity. While the procedure may restore joint stability, many individuals do not recover normal biomechanics or proprioception comparable to the uninjured knee. Some may also experience ongoing functional limitations in daily life.

Because of this variability—and the potential for diagnostic errors or alternative treatment options—it is advisable to seek a second opinion before proceeding with surgery. ACL reconstruction carries several documented risks, and many individuals may be candidates for less invasive approaches.

- Complications following surgery include anterior knee pain or discomfort during kneeling (affecting approximately 17% of adults), graft failure and loss of joint stability (reported in 5% to 29% of cases, with higher risk in younger patients). Additional potential complications include knee stiffness or limited range of motion (~5%), painful surgical hardware (~6%), infection (~1%–2%), and patellar tendon rupture or patellar fracture, particularly when bone-to-bone grafts are used.3-6

- The increase in ACL surgeries among youth, driven by rising participation in high-level competitive sports, has raised concerns. Research indicates that younger individuals may face a greater risk of postsurgical complications. For those who wish to preserve the body’s original structures, a nonsurgical approach such as Perc-ACLR may be worth exploring.

- A large-scale analysis of 160 clinical studies found that teens undergoing ACL reconstruction experienced a higher incidence of complications, including growth disturbances, skeletal changes, and a greater likelihood of rerupture requiring revision surgery.7

- Additionally, a 2010 study from Sweden reported that 60% of athletes (average age 26) who pursued structured physical therapy instead of surgery did not require ACL replacement and were still able to participate in sports.8

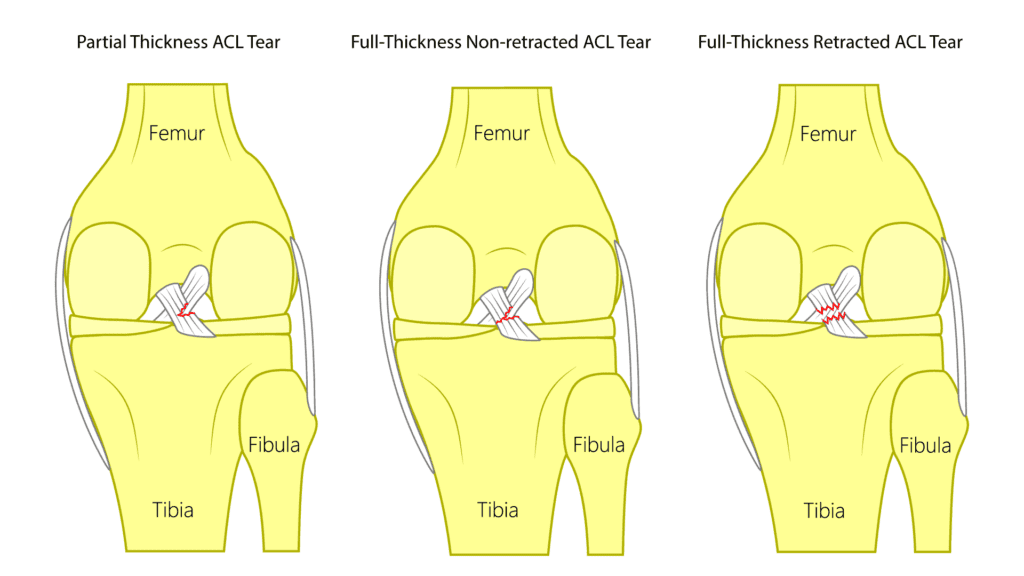

ACL injuries can be categorized in several ways, but for the purposes of interventional orthobiologic procedures, they are typically grouped into three main types: partial-thickness tears, full-thickness non-retracted tears, and full-thickness retracted tears.

Both partial-thickness and full-thickness non-retracted ACL tears may be candidates for image-guided procedures using the Regenexx Perc-ACLR protocol. These treatment options aim to support the body’s natural repair response and may offer an alternative to surgery. In contrast, full-thickness retracted tears are generally more severe and often require surgical reconstruction to restore function.

- Partial-Thickness ACL Tear:

This type of tear does not extend completely through the ligament. Imaging will typically show that a portion of the ACL remains intact and connected. - Full-Thickness Non-Retracted ACL Tear:

In this case, the ligament is fully torn, but the two ends have not separated. The structure remains in place, even though the tear extends across the full width. - Full-Thickness Retracted ACL Tear:

This type of injury involves a complete tear in which the ends of the ligament have separated or retracted, similar to how a stretched rubber band might snap back. These cases usually require surgical intervention.

ACL tears

Request an Appointment

References

1. Centeno C, Markle J, Dodson E, Stemper I, Williams C, Hyzy M, Ichim T, Freeman M. Symptomatic anterior cruciate ligament tears treated with percutaneous injection of autologous bone marrow concentrate and platelet products: a non-controlled registry study. J Transl Med. 2018 Sep 3;16(1):246. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1623-3. PMID: 30176875. PMID: 30176875. [Google Scholar]

2. Costa-Paz M, Ayerza MA, Tanoira I, Astoul J, Muscolo DL. Spontaneous healing in complete ACL ruptures: a clinical and MRI study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012 Apr;470(4):979-85. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1933-8. PMID: 21643922. [Google Scholar]

3. Freedman KB, D’Amato MJ, Nedeff DD, Kaz A, Bach BR Jr. Arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a metaanalysis comparing patellar tendon and hamstring tendon autografts. Am J Sports Med. 2003 Jan-Feb;31(1):2-11. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310011501. PMID: 12531750. [Google Scholar]

4. Webster KE, Feller JA, Leigh WB, Richmond AK. Younger patients are at increased risk for graft rupture and contralateral injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2014 Mar;42(3):641-7. doi: 10.1177/0363546513517540. Epub 2014 Jan 22. PMID: 24451111. [Google Scholar]

5. Burks RT, Friederichs MG, Fink B, Luker MG, West HS, Greis PE. Treatment of postoperative anterior cruciate ligament infections with graft removal and early reimplantation. Am J Sports Med. 2003 May-Jun;31(3):414-8. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310031501. PMID: 12750136. [Google Scholar]

6. Kovacic JJ in Complications of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Surgery, AAOS Monograph Series 2005. Accessed August 25, 2020.

7. Wong SE, Feeley BT, Pandya NK. Complications After Pediatric ACL Reconstruction: A Meta-analysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2019 Sep;39(8):e566-e571. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001075. PMID: 31393290. [Google Scholar]

8. Frobell RB, Roos EM, Roos HP, Ranstam J, Lohmander LS. A randomized trial of treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tears. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 22;363(4):331-42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907797. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2010 Aug 26;363(9):893. PMID: 20660401. [Google Scholar]